Adventures in a Golden Age of Storytelling by SAMUEL WILSON, Author of "Mondo 70," "The Think 3 Institute," etc.

Wednesday, August 31, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: August 31

Now that he had retired his alter ego Loring Brent and Brent's great creation Peter the Brazen, George F. Worts had more time The Gold Fist, premiering in this 1935 issue, was a rare Worts story that had nothing to do with either Singapore Sammy or defense attorney Gillian Hazeltine. It starts with a corny melodramatic premise that actually might have made a screwball comedy. Bill Lassiter, a playboy heir to a $13,000,000 fortune, makes a bet with his father's secretary, who's inherited a couple of million herself, that he can earn $50,000 in a year solely with his brains or hands. If he can't, the secretary gets all his millions. After establishing the premise, Worts fast-forwards to the twelfth month, which finds Lassiter hard up in Peru after getting conned out of a commission that would have won him the bet. He then just happens to see a Chinese woman murdered by a man without a nose. The murderer was after a package, and when the victim drops the package Bill sees what looks like a sculpted gold fist. He subsequently learns that this is no mere gold fist but the Gold Fist, a much-coveted Inca artifact that may convey long-forgotten engineering secrets of the great empire. Assured that he can get at least $100,000 for this treasure, Bill tracks down the noseless man and steals the Gold Fist. After sending him over the side of a steamer (see cover), Bill determines that the sculpture is "the fist of a wise man, clenched not in rage to strike but in determination to hold a secret." Lassiter now has to find a purchaser in New York to just make his deadline and win his bet. His quest is complicated by the lurking threat of a Bolivian conspirator, as well as his relationship with Joanna, an American woman he met and helped in Peru, whom he learns was held prisoner as an insane person on the steamer he sailed home on, only to be set free abruptly in New York. And just for the hell of it, back in New York his scientist cousin Homer has developed the ability to see when people are about to die. Parts One through Three of Four of this serial are available in three consecutive issues of Argosy at unz.org. Whether you'll really want to see the conclusion is another story.

In other serial action, Max Brand continues The Sacred Valley, Borden Chase concludes Bed Rock (it's about sandhogs, not cavemen), and Frank Richardson Pierce resumes the three-part Silver Thaw. This entertaining tale of a father-son logging feud inspired a spin-off series about a supporting character, the belligerent CCC worker Donnybrook McDuff. This consisted of at least one novelet and one serial, Donnybrook Shoots the Works, in 1936. The main standalone story this issue is a Hulbert Footner novelette featuring one of pulp's great female sleuths, Mme. Rosika Storey. In "The Richest Widow" the detective and her assistant Bella must figure out who made the title character and her new husband, an English actor, go out the porthole of the widow's ocean-liner stateroom. There are a lot of suspects, to be sure, since the widow was going to rewrite her will. Whodunit? Find out for yourself here. Shorts by Theodore Fredenburgh and Franklin H. Martin round out another solid -- if also goofy, in Worts' case -- 1935 Argosy.

Tuesday, August 30, 2016

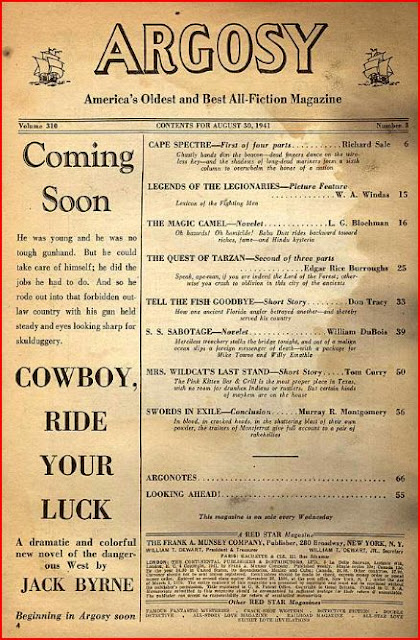

THE PULP CALENDAR: August 30

When last we left Tarzan, the ape man was trapped in a floundering pulp weekly. Technically speaking, he's a captive on board an old wooden cargo ship that's been commandeered by a Nazi, but before long he and several supporting players in The Quest of Tarzan will find themselves stranded by shipwreck on that island Edgar Rice Burroughs mentioned in last week's prologue -- the one settled by refugees from the Mayan Empire. Maybe they're Mayans because Burroughs liked writing Mayan-esque names.But they behave like most primitives who encounter Tarzan, taking him first as a god but later showing skepticism, debating his divinity and his fate in a tongue he hasn't yet figured out. Meanwhile, Burroughs still finds it amusing to torment his stereotyped society dowager, for whom the sinking of the ship and the escape to the island are but the latest indignities she protests pretentiously unless Tarzan gives her a death stare. I guess it was a matter of whatever it took to reach his word count. Here's how Virgil Finlay sees it:

Moving right along, this 1941 Argosy launches another serial, Richard Sale's thriller Cape Spectre. The hero has been sent to take over a spooky accursed lighthouse that can't seem to keep any personnel despite its potential strategic importance. Sale tips us off to the problem: pest control. This first installment closes with our man discovering a rattlesnake in his bed. He finds something else: his predecessor is supposed to be long gone, but evidence indicates that the lighthouse radio was in use just minutes before our hero arrived. Hmmm...

This issue also concludes Murray R. Montgomery's rakehelly serial Swords in Exile, but since I came in too late to really immerse myself in the thing, I let it go with no further comment. As for the rest:

Two latter-day series characters (or sets of characters) take up most of the remaining space. L. G. Blochman's "The Magic Camel" continues the misadventures of Gundranesh Dutt, a "babu" (i.e. a native of India trained for the colonial bureaucracy) who runs the Grand International Detective Bureau in Calcutta with help from his cousin Danilal. Gundranesh weighs in at approximately 300 pounds, while illustrators portray Danilal as a near twin to Mahatma Gandhi. These are comedy stories, most of the comedy supposedly resulting from the funny way the Dutts talk. To be more specific, these are dialect stories in a way that the superficially comparable Charlie Chan novels are not. Chan is challenged by English grammar but clearly has a brilliant mind. Gundranesh Dutt does not.

"Cousin Danilal!" the fat babu exclaimed, "You are three days premature in semi-fortnightly visit from Barackpore. Scarcely recognized you in new green turban. You have also altered mustache with upward curls at terminals. Disguise, Cousin Dani?"

"No disguise," said Danilal Dutt. "Was merely testing imported American invention for curling hairs with heated iron device. Quite efficacious."

Try to deal with that for the length of a Short Novelet. Until recently, if not still, you could still get away with this sort of Indian dialect in comedy: verbose run-on sentences with a noticeable lack of pronouns. You're probably hearing the stock voice in your head. Anyway, as the illustration shows you, this is a slapstick story involving much chasing about on camel, same being pawn in jewel-smuggling operation unknown to Dutt. It's pretty sad stuff, not really funny enough to redeem its racism.

William DuBois' "S.S. Sabotage" also spotlights an ethnic detective of a sort. Willy Emathla, a college-educated Seminole, is part of a three-man team along with his millionaire mentor, "ash-blonde giant" Mike Towne, and Towne's other protege, two-fisted playwright Christopher Ames. The three work together -- Emathla is always deferential, but indispensably supercompetent, especially when violence is called for -- in a series of stories pitting them against the traitorous Paul Derring, described as resembling the actor John Gilbert. Theirs is an action-packed series, but none of the protagonists really has much of a personality. Willy behaves exceptionally here -- he's usually more like a Vulcan -- by applauding the premiere of Ames' latest play with a war whoop --before he prevents Ames' assassination by one of Derring's goons. Our heroes have to stop Derring from seizing a British freighter in the Caribbean without violating U.S. neutrality. Inevitably it loses some of pulp's buccaneering swagger in its sides-taking relevance to the world war, but "S.S. Sabotage" is a good story, particularly by Argosy's 1941 standards.

The rest of it consists of another too-slick story by Don Tracy, who was in last week's issue, and another in T. T. Flynn's comedy-western series about "Mrs. Wildcat," a tough Texas saloonkeeper. "Mrs. Wildcat's Last Stand" also features an educated Indian who actually gets the girl -- a white girl who was his college sweetheart, both being archaeologists -- after being mistaken for a savage kidnapper. Turns out the admirable young man is just trying to help stop his old man from trading invaluable tribal artifacts for firewater.

Next Tuesday we'll wrap up Tarzan, continue Cape Spectre, visit Chinatown and meet men from Mars while Argosy gets an injection of pure pulp from E. Hoffman Price. So long for now from 1941!...

Monday, August 29, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: August 29

This 1936 Detective Fiction Weekly has a strong-looking lineup with an emphasis on the feminine. It features two female series characters, Whitman Chambers' Katie "The Duchess" Blayne" and Eugene Thomas' antiheroine Vivian "The Lady From Hell" Legrand. Those are women written by men, but before we move on I always have to pause when confronted with a set of initials and no biographical info. So who was M.I.H. Rogers, anyway? Rogers published most of the time in Street & Smith's detective pulps, this issue's "The Push-Over" being the author's first appearance (of two) in DFW. More familiar to DFW readers was T. T. Flynn, whose cover story apparently had nothing to do with his common protagonists, Mike and Trixie. Tom Curry was trying to launch a series about a secret agent named George Devrite. He'd introduced the character just last week and would publish the third Devrite story in as many weeks next issue before a hiatus until November. There are also short stories by Norman Daniels and Anthony Rud, while Max Brand concludes his serial The Granduca -- which premiered with a cover image of a woman wielding a gun back on July 25. Two cheers, at least, for female empowerment this issue, and who knows how many more are in order?

Sunday, August 28, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: August 28

The cover threatens a fascist takeover of the U.S., but the first installment of Martin McCall's Kingdom Come in this 1937 Argosy plays out more like a horror story. A tough, obsessed G-Man -- he joined the force after his wife died accidentally during a gangster shootout -- investigates the fatal mutilation of a fellow agent and enters a strange marsh country of idiot albino hillbillies, where the soil shows unexpected evidence of artillery fire, and where a hillbilly settlement is finally wiped out by poison gas. That's where it starts to head toward modern conspiracy-thriller territory. "Martin McCall" was a house name at Munsey that was later assigned to E. Hoffman Price when he wrote the "Matala, the White Savage" stories for the company's Red Star Adventures in 1940. Whether McCall was always Price -- the name first appears, reportedly, in a 1932 nonfiction squib -- I don't know. In any event, that creepy opener fronts a strong issue of the venerable weekly, which also boasts a Nick Fisher-Eddy Savoy novelette by Donald Barr Chidsey and a Foreign Legion adventure by the master of that subgenre, Georges Surdez. There's also a fish-out-of-water golf story by Howard R. Marsh, a couple of northwestern shorts by Foster-Harris and Samuel W. Taylor, serial chapters by Arthur Leo Zagat and Bennett Foster, and a Frederick C. Painton oddity about a ventriloquist and a psycho stoker alone in a lifeboat after a shipwreck, which goes in an all-too-predictable direction when the men land on an island and are captured by idol-worshipping savages -- you know, the sort who'll worship anything, including a ventriloquist's dummy. It's politically incorrect, sure, but its retrospective campiness adds to its entertainment value today, and Painton usually was a pretty good writer regardless of content. 1937 was arguably Argosy's last really good year, and this issue mostly lives up to the expectations my claim might create. Like many issues from that year, it's been scanned and made available online, so you may still be able to track it down.

Saturday, August 27, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: August 27

There's nothing special about this 1938 Argosy cover, though I like the giant ghostly head motif, but this issue is noteworthy because, though the author of Lost House isn't identified up front, the serial makes this a rare non-romance pulp headlined by a story written by a woman. In fact, it's Frances Shelley Wees' only contribution to pulp fiction. She had established herself as a mystery novelist earlier in the decade and would continue publishing books for decades more. I actually have this issue in my collection, but it's a little on the ratty side so I didn't want to subject it to scanning. The reason I have it is that it has the second part (of three) of Donald Barr Chidsey's Midas of the Mountains. Last week's issue had a nice Rudolph Belarski cover, but I felt another Aug. 20 magazine had more historical significance. Anyway, along with Wees and Chidsey this issue features a Handsled Burke novelette by C. F. Kearns -- and those are usually pretty good -- and a novelette by Robert E. Pinkerton, along with stories by John Randolph Philips, Howard Rigsby and Richard Howells Watkins, and the latest installment of Bennett Foster's western Cut Loose Your Wolf. Next Saturday you'll see my copy of the next 1938 issue, which sends Frederick C. Painton's Dan Harden to Syria....

Friday, August 26, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: August 26

Here's twofold exploitation in a 1939 Detective Fiction Weekly. Warren William had made a hit playing Louis Joseph Vance's Lone Wolf, Michael Lanyard, in The Lone Wolf Spy Hunt earlier that year, and Columbia Pictures, which had been making Lone Wolf pictures sporadically for years, was now committed to putting out films with William more frequently. He'd play the part eight times more in the next four years. To take advantage, DFW makes a big deal out of reprinting the 25 year old novel with which Vance introduced the character. Since The Lone Wolf originally appeared in Munsey's, I imagine the Munsey corporation didn't pay Vance much, if anything, for the reprint. At least they didn't go for a blatant Warren William on the cover. It probably was a sign of trouble at Munsey that both DFW and Argosy were actually publicizing reprints in 1939. In Argosy's case it was A. Merritt's Seven Footprints to Satan. For DFW the reprint overshadows an okay-sounding lineup. Richard Sale contributes a Candid Jones story, while Roger Torrey continues the adventures of Mike Hanigan and Irving Kowalski with the eighth novelette in a series that started in July 1937. Hugh B. Cave also has a novelette and Bert Collier, R. V. Gery and Herbert Koehl have short stories. It's a shame all this new material is forced to the background by a reprint, but I suppose it wasn't as easy in 1939 to find an old copy of The Lone Wolf as it would be now to find something comparably old. In that case, I suppose DFW was doing a public service -- at a profit, of course.

Thursday, August 25, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: August 25

You can think of this 1932 pulp as Short Stories' victory lap. Back in March of that year, the Doubleday, Doran magazine increased its page count from 176 to a monstrous 224, with the obvious purpose of topping the 192 pages of its twice-a-month competitor, Adventure. Whether Short Stories had anything to do with it or not, in August Adventure cracked, cutting its page count in half while cutting its price from a quarter to a dime. Perhaps not coincidentally, this proved to be the last 224 pager for Short Stories. It reverted to 176 pages the following issue, September 10, and held that ground for another decade, all the while grinding out two issues a month long after Adventure had gone permanently monthly. But if the Aug. 25 issue as a whole is a victory lap, its "book-length novel," J. D. Newsom's A Man Stands Alone, was an 87 page slam dunk. I don't know how big the typeface was during this period, or how many lines there were to a column, but 87 double-column pages pretty much is a book-length novel -- and probably a good one, as Newsom was one of the top Foreign Legion writers. The rest is gravy: the conclusion of a Robert Ormond Case serial; novelettes by R. V. Gery and Ladbroke Black; short stories by Leo F. Creagan, Douglas Leach, Robert E. Pinkerton and Sewell Peaslee Wright. That's not quite the all-star lineup Adventure could publish at its best, and I don't know if I'd call them "All headliners," but in 1932 it would do quite nicely.

Wednesday, August 24, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: August 24

Frederick Faust's last story about Tizzo the Firebrand -- written, like all the others, under the alias of George Challis -- was actually the first of the series that I read. It was the only complete Firebrand story in the unz.org Argosy trove, but it was impressive enough to inspire me to start a Tizzo collection of his original appearances. "The Pearls of Bonfadini" concludes a sequence of four novelettes (following three short serials) in which the half-English, half-Italian redhead -- who favors an ax despite the sword shown on the cover -- falls into then fights his way out of the orbit of Cesare Borgia. Tizzo enjoyed meteoric success as an Argosy character, appearing on seven covers between late November 1934 and this end point in August 1935. Whether "Pearls" was meant to close the series all along or circumstances prevented Faust/Challis from writing more, I don't know. Regardless, the series is a classic of swashbuckling.

In addition, Frank Richardson Pierce begins a three-parter, Silver Thaw, that can be had complete at unz.org, while Faust continues the western serial The Sacred Valley under his more familiar identity as Max Brand, and concludes The Blackbirds Sing under the even less familiar pen-name of Dennis Lawton. The issue's fourth serial is part two of Borden Chase's Bed Rock, another of his dangerous-job tales of tunnel-digging sandhogs. The only real standalone stories this issue -- admittedly, you can enjoy "Pearls," as I did, without having read the earlier Tizzo pieces -- are Foster-Harris's action piece "The Rattler Whirs" and a gruesome short by Houston Day, "Cure for the Headache." This issue may be a little Faust-heavy for some, but it's still another outstanding Argosy from what I consider the venerable weekly's peak period. Browse through it at your leisure through this link to unz.org.

Tuesday, August 23, 2016

VINTAGE PAPERBACK OF THE WEEK: William Ard, WANTED: DANNY FONTAINE (aka AS BAD AS I AM, 1959-60)

William Ard never published in the pulps but went straight to paperback original novels, becoming a prolific author under numerous names before his untimely death from cancer at age 37 in 1960. As Jonas Ward, he wrote the Buchanan novels that inspired the 1958 Randolph Scott-Budd Boetticher film Buchanan Rides Alone. Ard published this novel in hardcover in 1959 as As Bad As I Am. That title is taken from some jailhouse graffiti recited by the protagonist, ex-con and ex-actor Danny Fontaine:

As good as you are, and as bad as I am, I'm as good as you are. As bad as I am.

With the publication of When She Was Bad in 1960 As Bad As I Am became the first of what proved a tragically short-lived series. Dell clearly hoped to market them as the Danny Fontaine novels, no matter what title Ard preferred. This 1960 re-release also required a slight rewrite, since Ard had changed his hero's first name from Mike to Danny from one novel to the next. Wanted: Danny Fontaine is the first Ard novel I've read. It might be described as a hard-boiled fairy tale, often grittily realistic in its depictions of crime and police procedure, and often too romantic to be true.

Fontaine is a three-time loser who got in trouble each time out of a compulsive desire to help a pretty girl. His parole board's perverse plan to reform him is to forbid him from dating women for eighteen months. Danny's determined to tough it out while living off rent on the apartment building he owns with his sister in a rapidly de-gentrifying neighborhood. In a familiar pop trope, his sister is married to a tough cop who distrusts Danny. But in this story the cop's the man you can't trust.

Even though Danny assumes he can't get work as an actor because of his criminal record, he's drawn back into the thespian milieu, impressing the casting director of a soap opera with his reading of audition lines describing prison life. He meets cute with Gloria Allen, a showgirl on the verge of a big break on a TV variety special starring a thinly-disguised satire of Jackie Gleason. Gloria gets a parallel storyline showing the pitfalls of her possible rise to stardom, including a date arranged by the crypto-Gleason's agent with a young lawyer negotiating the comic's new contract -- a date the lawyer expects to come with a bonus at the end. One of the novel's too-good-to-be-true elements is its revelation of the lawyer as a true gentleman at heart and a good guy who wants to do Gloria a good turn by helping Danny in his hour of crisis.

The crisis comes when Danny learns that his cop brother-in-law has set up two prostitutes in the apartment building, taking a cut of their earnings as protection money. A showdown leads to a struggle for the cop's gun in the marijuana-scented apartment that ends with the cop shooting himself by accident. Convinced that there's no way he could make the dead man's brother officers believe the truth, Danny runs, eventually taking shelter in Gloria's apartment.

It seems that everyone but the police is willing to believe Danny's story. Ard does nothing in this novel to flatter cops, who are shown, especially in the upper ranks, to be willing to lie and cheat to get high-profile convictions under unceasing pressure from their superiors. One police captain in the particular gets the truth of the incident from the prostitutes (some readers will object to their blatant Puerto Rican ethnicity), but ruthlessly convinces them to change their story to one portraying Danny as the aggressor. As the manhunt for Fontaine becomes front-page news, Gloria's future in entertainment seems to disintegrate once the comic's entourage learns of her relationship with the fugitive, but the smitten Gloria couldn't care less. Despite the lawyer's game best effort, Danny feels compelled to run again, only to be shot and caught. This is his moment of maximum peril as Ard sells the threat of torture or worse at the hands of the police. Fortunately, private detective Barney Glines -- a name Ard had used before, though he's supposedly not the same character from earlier novels -- to help the lawyer outmaneuver the police and track down the one man whose eyewitness testimony can counter the prostitutes' perjury. It all comes to a melodramatic courtroom climax, punctuated by the guilty police captain blowing his brains out. All ends happily, and in When She Was Bad Fontaine will become Glines' protege.

Somehow, over 219 paperback pages (in a sturdy edition perfectly shaped for reading) Ard maintains a tricky balancing act between noir and urban fable. When the novel goes hard-boiled, it's utterly convincing, and when it waxes romantic it has you enough on the side of his hero and heroine that you forgive the virtual whimsy of it. In the end I guess it's less a mix of styles than Ard doing his own thing in a unique and unflaggingly entertaining way. It's sad to realize that a year after As Bad As I Am came out in its original form, Ard was dead. There remains plenty for me to discover -- I especially want to try a Buchanan now -- but who knows how good he would have gotten in the long run?

THE PULP CALENDAR: August 23

By this time in 1941, Argosy's longtime stablemate Detective Fiction Weekly had ceased to be a weekly in another sign of the dire straits facing the Munsey Corporation. For all I know, by the time this issue hit the newsstands the decision had already been made to end the venerable weekly's weekly status. The proof wouldn't come for another month. For now, Argosy not only soldiered on but played an ace. Edgar Rice Burroughs' Tarzan was born in another Munsey magazine, All-Story, back in 1912. Throughout his career, the ape-man bounced back and forth between the Munsey mags and the McCall company's Blue Book and Red Book, depending on who paid Burroughs more. He had last appeared in Argosy in a 1938 serial. Perhaps now the Munsey people thought Tarzan could save Argosy, at least for a little while.

Virgil Finlay had been doing occasional interior illustrations for Argosy since 1939.

This was not one of his finest hours.

The Quest of Tarzan gets off to a dubious start with some anticipatory exposition about Mayans settling islands in the South Pacific before moving on to the negotiations of a German ship owner and an Arab slave trader, the latter promising to provide the former with a wild man to exhibit in circuses. The German is briefly taken aback when told that the wild man is white, but once informed that the wild man is also "English born" the ancestral hatred takes over. For the Arab, apparently an old enemy of Tarzan, this will be sweet revenge. He's somehow learned that Tarzan got bonked on the head or something (in a previous adventure?) and has lost his memory, reverting to his most primitive self. I'd seen the amnesia gimmick done in the 1929 silent serial Tarzan the Tiger; had Burroughs himself done it before? Anyway, he's wandering through the jungle until the slavers capture him and deliver him to the German. Meanwhile, World War II has broken out and another German passenger takes advantage of the fact that the first German was sailing under a British flag to confiscate the vessel in the name of der Fuehrer. Tarzan acquires some cellmates, kills a snake and regains his memory, most likely because Burroughs had tired of the amnesia gimmick already. The ship takes on some British prisoners, including a stereotypical dowdy dowager and her more hip children. This is exactly what you want to do with Tarzan of the Apes: stick him out at sea on a boat. I expect he'll meet some misplaced Mayans before this three-parter is open, but I'm not sure you can take that for granted.

This is another Argosy without a table of contents on the Fiction Mags Index, but since all three issues containing The Quest of Tarzan have been scanned and made available online, I can fill in that gap.

While the Tarzan story features an evil German, Japanophobia prevails in this issue by a 2 to 1 margin. Sinclair Gluck's novelette "No Ticket to Nippon" has American gangsters helping the Japs smuggle a strategically valuable element out of the country. It sports some fragrant Japano-jibberish from the Nipponese villains, e.g. "Ah ha! Big dirty trick on me, please, Captain Coast Guard! I notta knowing thatta stuff! White man fooling Japanese skipper, please. Telling that cement! Ah ha! Dirty work, I think so!" You can easily imagine Jerry Lewis or Mickey Rooney playing the part. The Japanese retain some dignity in Hal G. Evarts' "Colonel Coolie," perhaps because, with the action set in China and his heroes Chinese, Evarts has no excuse to resort to vaudeville pidgin. In the story, a coolie survives torture and saves his unit virtually by accident, succeeding where the stratagems of his westernized, academy-trained commanding officer had failed.

I didn't bother with this issue's installment of Murray R. Montgomery's Swords in Exile, another in a sort of anti-Musketeer series about Cardinal Richelieu's personal troops, because it was part five of six. I did read the conclusion of Walt Coburn's two-parter Town Marshal because the previous issue, containing part one, is at unz.org. It's a typical Coburn combo of violent and romantic passion, a vicious outlaw being offered a pardon in order to clean up a still-more vicious cow town where he encounters an old flame and the old enemy she married. Coburn teases a romantic triangle involving the outlaw-turned-marshal, the young woman who inherits a ranch, and her hotheaded boyfriend, but arranges for age-appropriate pairings by the end. I can't say whether whisky fueled the writing here, as it was often supposed to have in Coburn's later career, but there's an energy here missing in most of the other stories. I'm thinking of two pieces that hardly have business in a pulp magazine. In Elmer Ransom's "With Work to Do," a disgraced, widowed doctor befriends an injured beaver and spoils the animal until it's ostracized by its own kind, only to be inspired when the beaver mans up and takes charge in a crisis caused by the man himself. Don Tracy's "Bunny Rabbits" is inexcusable slop in which a newspaper circulation stunt offering rabbits as incentives to newsboys goes haywire. I guess the slicks wouldn't have these stories, but they seemed respectable to Argosy. Stuff like them was helping to kill the venerable weekly, on top of Munsey's self-destructive overexpansion over the last two or three years. For the next two Tuesdays we'll continue to follow Tarzan's misadventure and see if anything else is salvageable from these dark days for Argosy.

Monday, August 22, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: August 22

Johnston McCulley's tales of Zorro represent just a fraction of all the pulp fiction he wrote about Spanish or Mexican-ruled California. In fact, McCulley didn't become a prolific writer of Zorro stories until relatively late in his career, after many other pulp markets had dried up or died on him. If anything, he seemed reluctant for a long time to return often to the character that gave McCulley his place in pop-culture history. Maybe the character gimmick we now identify with Zorro -- the hero who pretends to be a dull fop in civilian life -- bored him. Yet he remained fascinated by the setting and the period, and during the 1930s especially wrote numerous swashbucklers set in what this 1936 Argosy exploitatively calls "Zorro-Land." That tantalizing label tempts us to think of McCulley setting all his California creations in a "universe" where his heroes might have interacted with each other, depending on chronology. I doubt whether the thought ever occurred to him. Here was a writer who was happy to write tales of the lisping thief Thubway Tham ad infinitum (or nauseum), but when it came to Old California it seems that McCulley really preferred to come up with a new concept for a hero, to start over from scratch, as often as editors would let him. And in fact there's a freshness to these miscellaneous California chronicles that's missing in the later Zorro stories I've read. I'd rather give this Don Peon a try than have old Don Diego go through his paces yet again. I probably will give at least this first installment of the Don Peon serial a try, since I must have this issue to complete Eustace L. Adams's serial Brave Men Die Hard. For my trouble I'll also get novelettes by Cornell Woolrich and Donald Barr Chidsey (the latter apparently outranked by McCulley if by few others in this period), short stories by James Francis Dwyer, Allan Vaughan Elston, Frank H. Martin and Theodore Roscoe, and a serial installment from Arthur Hawthorne Carhart. Not a bad package, theoretically, and probably not expensive despite McCulley and Woolrich's canonical names. Perhaps we'll have a chance to discuss this issue at greater length sometime....

Sunday, August 21, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: August 21

Here's a 1937 Argosy without a table of contents in the Fiction Mags Index. Fortunately, a site dedicated to the pulp writings of L. Ron Hubbard has this issue covered with a detailed table. For Hubbard fans or followers, this issue is extra-special because the great man has a letter in Argonotes along with his story "Nine Lives." In the letter, Hubbard defends "fast-production" writers like Frederick Faust and H. Bedford-Jones against snobby critics, crediting them with more nimble brains and "unconscious technique," while saying of himself that " If I write less than fifty thousand a month, my idea-machine practically breaks down." As was often the case in the second half of the 1930s, Donald Barr Chidsey gets the cover with the debut of a new series. "Call Me Mike" introduces Mikkud-Phni Luangba, heir to the real of Kamorriri, and his American companion/bodyguard George Marlin. Mikkud-Phni, aka "Mike," has adventures all around the world when he's not studying at Princeton. The running gag is that Marlin usually is forced into frantic action to rescue Mike, while the prince views everything with placid bemusement -- though he shouldn't be underestimated in a fight. Chidsey published at least three more Mike stories: two in September 1937 and one in 1940. There may be more, since the Mike series isn't recognized in the Fiction Mags Index. The first three stories have "Mike" in the title, but the 1940 story is "Flight to Singapore," and other Mike stories may be similarly obscured. I've read a couple of the Mikes, and they're mildly amusing, though you can see how they'd quickly grow monotonous. Along with these highlights the Aug. 21 issue features serial chapters from Bennett Foster, John Hawkins and Arthur Leo Zagat and stories by Frank Richardson Pierce (possibly a No-Shirt McGee), Garnett Radcliffe and Bertrand L Shurtleff. Hubbard's stuff was pretty entertaining in these early days of his career, so this issue's probably a pretty good overall package.

Saturday, August 20, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: August 20

Something important is missing from this 1941 cover: the word "Weekly." Since its founding as Flynn's in 1924, this magazine had maintained a weekly schedule as the stablemate of Argosy for the Munsey corporation. Now Munsey could maintain that schedule no longer, crippled by a harebrained brand expansion that had shown few results. The last weekly issue bore an August 2 cover date. How much time passed between that issue and this one appearing on newsstands I don't know. In any event, Detective Fiction now became a true biweekly title, as opposed to "twice a month" magazines like Short Stories that always were dated the 10th and 25th of the month. If there were five Wednesdays in a month, as would be the case in November 1941, you'd get three issues of Detective Fiction. That situation didn't last for long, however, since with Munsey's fortunes still dwindling Detective Fiction became a monthly in April 1942. Popular Publications took over in 1943, but while they upgraded Argosy into a long-running men's magazine, they finally killed Detective Fiction in the summer of 1944, only to revive the title for a short-lived mini-pulp in the 1950s. As you see, Munsey had come up with some ugly packaging for the former DFW that would only get uglier over the next year. Inside, you could still find familiar faces, whether authors like Richard Sale or characters like T. T. Flynn's Mike and Trixie (who made their last appearance until 1951 in this issue) or J. Lane Likletter's Paul C. Pitt. But there's no denying that a once-mighty magazine was a shadow of its former self in more ways than one.

Friday, August 19, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: August 19

Here's one Western Story cover from 1939 that doesn't quite work for me. In his focus on the close up of hands and weapons H. W. Scott loses some of the sense of height and peril -- despite the bird in the distance -- that this predicament should have. Of course, if the real subject is mutually assured destruction, the cover does have a point. Inside, this issue is dominated by L. L. Foreman's "book-length novel" Bullet Blockade. At 53 double-column pages, this one is a relatively plausible claimant to that much-abused title, and it could well be a good one, since I've liked what I've read of Foreman so far. It leaves room for only two more short stories, by B Bristow Green and Tom Roan, along with this week's installment of Bennett Foster's serial Blackleg. Of course, each Western Story comes with a quota of nonfiction and regular columns. On any given week it looks like it was definitely worth a dime.

Thursday, August 18, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: August 18

Oh, come on, cover artist! Don't tell me you couldn't do a better job teasing a story called Murder at the Nudist Club. If you couldn't, or if Detective Fiction Weekly wouldn't let you, than the Munsey Corporation should have left that title to the spicy pulps. Of course, Fred MacIsaac probably could get away with more in pure prose inside. While he launches his five-part serial, Richard Howells Watkins tries to start a series about a policeman named Pete Slocum with the novelette "The Crimson Harbor." According to the Fiction Mags Index, Slocum would appear only once more, in November 1934. For collectors and historians, Cornell Woolrich's second pulp story, "Walls That Hear You," is probably this issue's main attraction. You also get stories by Charles Molyneux Brown, Laurence Donovan, J. Allen Dunn and John H. Knox. If those names don't draw you, I suppose browsers in 1934 would at least have been curious to see the inside illustrations for the cover story.

Wednesday, August 17, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: August 17

I wonder whether The Strike-Breaker is the hero or villain of Fred MacIsaac's 1935 Detective Fiction Weekly serial. Is he the scruffy fellow with the bomb, the natty man with the badge, or neither? Either way, the serial is something I'd like to read for what it might tell us about pulp attitudes toward organized labor at a time of high tension between labor and capital. Along with MacIsaac, DFW sees fit to hype stories by T. T. Flynn, Richard Howells Watkins and Ray Cummings, the latter continuing his sci-fi "Crimes of the Year 2000" series with "The Bandit of Pontoon 9." There are also short stories by two old-timers: Robert McBlair, who'd been writing since 1915, and Robert W. Sneddon, who started back in 1912. There's also a ghost-written serial memoir, I Was a Public Enemy, a column on "Weird Weapons of Gangland," and an article on "The Rat of Rat River," among other nonfiction items. An intriguing package, overall.

Tuesday, August 16, 2016

SERIAL PULP: The Spider's Web (1938), Chapter 6: SEALED LIPS

A co-production with the Mondo 70 movie blog...

The Octopus's gangsters (led by Marc Lawrence) already think they've killed criminologist and amateur magician Richard Wentworth and are trying to take out The Spider with a falling spotlight as this chapter opens. Of course, Wentworth's (and The Spider's) lovely assistant Nita Van Sloan gives a timely scream to signal that The Spider should step out of the falling object's way. The thwarted gangsters make a fighting retreat, convinced that they were at least half successful until they see Wentworth walk out of the bus station turned theater. As Nita had explained earlier to the benefit organizers, the gangsters had shot at a projected image of Wentworth, apparently lacking any depth perception to help them detect the trick. To account for his absence during the mayhem, Wentworth claims that the gangsters had knocked him out and left him in his dressing room. No one finds this odd, considering that the gangsters had tried to kill him earlier. But never mind. My favorite thing about this whole scene is how baffled the organizers are by Nita's explanation of the projection trick. Should I explain in more detail how it worked? she asks. Cut to The Spider skulking outside. Back to Nita: "Now do you understand?" They may not, but they're not going to admit it.

The Octopus is strangely forgiving of this latest failure, given how casually he's killed failures earlier. A great general takes minor setbacks into account, he says before moving on to his next project: payroll robberies. Again in a peculiarly chipper mood, he promises big bonuses should the caper succeed. He has reason to be confident this time since he's got an inside man -- a woman, actually, -- at the bank. This receptionist can tap into executive calls to find out when money is arriving or departing. She then passes notes to The Octopus's man. Meanwhile, Wentworth has had the benefit tickets purchased by the gangsters checked for prints. One set matches a police file that gives Wentworth a name to work with. As Blinky McQuade, he finds this man to give him a tip that the police are going to tap his phones. Wentworth expects him to call his boss right away to stop all calls to this phone, and he's planted his minion Jackson in the place as a drunk to get the number. We've already seen Jackson display a now-obsolete talent for listening as someone dials a number on a rotary phone. He can identify each digit in the number by the time it takes the rotary dial to circle back into place. Once the crook finishes dialing, Jackson attacks him and knocks him out. Blinky reappears, now speaking with Wentworth's voice, to call the cops for a trace on the number, which turns out to be the Commerce Bank where that receptionist works.

We've already met the receptionist. During the chase as the gangsters fled the bus station, their car clipped a newsboy and knocked him down in the middle of the street. Wentworth stops his car to help the lad, and the boy's older sister ends up being the crooked receptionist. After snooping on her method for relaying info to the Octopus, Wentworth and Nita snatch her off the street, Wentworth using the same finger-in-the-back technique that Blinky used on a cop a few chapters ago.

Meanwhile, The Octopus's men pull off the robbery but the gangster who'd been blackmailing the receptionist is killed in a shootout. That hard-luck newsboy is practically trampled by a fleeing gunman, but recognizes the man as a nearby garage worker. Wentworth is exultant at an apparent big break and gathers Jackson and Ram Singh for a stakeout of the garage. They find some gangsters driving away, apparently to deliver the bank loot someplace. The good guys follow but are eventually made by the suspicious gangsters, who start firing bullets and lobbing grenades at the pursuing vehicle. Wentworth changes to The Spider and prepares for a car-to-car attack. There's one long shot shot of the car stunt shot on location, but most of the action in both cars is done with process shots. The gangster car goes out of control once The Spider jumps on board and crashes into an electrified power-plant fence for our cliffhanger. This episode again shows the above-average competence of the Octopus gang, since they score another win with the bank robbery, and despite plenty of action the focus this time is more on detective work. The episode is slowed a bit by the need to introduce two possibly major new characters but it's still pretty good. If you're really worried about The Spider's fate, we'll have the answer for you sometime next week.

THE PULP CALENDAR: August 16

None of my usual magazine sources looked that good for this day, so it's about time I said something about the love pulps. There's actually not much I can say about them. They certainly were immensely popular in their day, but a glance through the Fiction Mags Index shows considerable modern neglect. Let's face it: romance is probably the last thing we think of today when we think of pulp fiction. It gets a pass from some when it's a genre hybrid like Ranch Romances that has some credibility as a western, but otherwise it has no place in what retroactively has been defined as a man's world. You see the same thing in the history of comic books; romance titles proliferated throughout the Golden Age of Comics, with Jack "King" Kirby as one of the leading practitioners, but you can't even imagine a market for romance comics today, nor could you have for the last forty years. Yet back when "pulp" meant a publishing format rather than a sort of meta-genre, you could not have thought of the word without respecting the popularity of romance pulps. Love Story (today's cover comes from 1930) was Street & Smith's most popular title for much of its existence, and in 1930 it apparently had the biggest page count of the publisher's weeklies. Like Western Story and Wild West Weekly, it maintained a weekly schedule until 1943, long after Detective Story had dwindled to twice-a-month and then monthly. Love Story died with most of the rest of the Street & Smith fiction line in 1949, but was revived by Popular Publications for a short run in the 1950s. Meanwhile, Ranch Romances outlasted all other pulps (those that didn't convert to digests or men's magazines, that is), albeit in much-diminished form from 1958 through 1971.

Needless to say I've nothing to say about the authors of this issue. I will note that the cover is exceptional, but not unique, in its lack of a man. The woman's beau presumably is represented by the letter in her hand. And that's all I've got. I do wonder whether there was as great a difference in content between pulp and slick romance as there was (leaving aside differences in literary quality) between pulp fiction as we understand it today and slick fiction in general. There may simply have been so great an appetite for romance fiction that the slicks couldn't hope to satisfy it. Now, of course, there are Harlequin Romances and their competitors exist to satisfy what appetite remains. Considering that paperback original romances continue to be published after the demise last year of the remaining western series paperbacks (in print, at least) and most of the Gold Eagle action line, I guess that appetite remains relatively healthy.

Monday, August 15, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: August 15 -- BONUS CONTENT

The Fiction Mags Index doesn't have a table of contents for the August 15, 1936 Argosy, but as I mentioned a week ago, someone recently scanned and uploaded the issue to the Yahoo pulpscans newsgroup. I now can provide that table of contents.

This issue is most noteworthy for beginning a posthumous run of stories by Robert E. Howard. A total of five westerns appeared before the end of the year. This issue's "The Dead Remember" was not Howard's Argosy debut; he'd actually placed the story "Crowd-Horror" back in July 1929. "The Dead Remember" is a chilling short story in what by default is Howard's late style: a pseudo-documentary format in which the story is told through letters, depositions etc. A cowboy writes to a friend predicting his own death, believing himself under a curse for having murdered a black man and his wife. For what it's worth, Howard invests the victims with more dignity than you might expect from him. There's room for queasy speculation about the cowboy's obsession with the black woman's checkered dress, how he writes of hallucinating so that a cloth he uses to clean his gun looks like a scrap of her dress. In classic horror-twist fashion, he dies because a scrap of the dress itself is wadded into his gun. Is this a supernatural transformation or did he actually take a hunk of the dress? Did he actually do more to the woman than shoot her? That aside, it's a nice distancing touch to have the avenging ghost introduced in someone's dry deposition, perfectly clueless as to the import of her presence. I don't care much for Howard's comical westerns, but this is strong stuff.

But if you like bad western comedy, this issue has one of W. C. Tuttle's Dogieville stories, though western fans (who don't like their genre mixed with spook stuff) will better appreciate the conclusion of Bennett Foster's Thief-Lover Valley. Ared White is this issue's headline author, and while I didn't like the one story of his I've read so far I suppose he deserves another chance. Arthur H. Carhart begins a sci-fi serial while Eustace L. Adams continues Brave Men Die Hard and Frank Richardson Pierce and Franklin H. Martin contribute short stories. For me this issue's main virtue is that it continues the Adams serial, of which I own the first two installments. I suppose the Howard story can be found in many places easily enough, but if you download this Argosy and read it for the first time there you're in for a treat.

THE PULP CALENDAR: August 15

This 1932 issue marks the end of the line for Adventure in its classic 192 page form. With the September 1 number the perhaps-greatest of pulps slashed its page count by half, to 96 pages, and cut its price by more than half, from 25 cents to a dime. Adventure maintained its twice-a-month schedule until the end of May 1933, when it went monthly while raising the page count to 128 pages. Even then you got less for your dime, at least quantitatively, than in the weekly Argosy, while Short Stories, Adventure's most direct competitor continued to deliver 176 pages twice a month after its chicken-game jump to 224 in 1932. What happened to Adventure? I don't know the business end of pulp enough to say, but I know the reading end enough to say it didn't deserve this humbling. The magazine's decline after the 1927 departure of longtime editor Arthur Sullivant Hoffman is not self-evident to me. Hoffman's star writers still appeared regularly. The August 15 issue, for instance, features the opening of an Arthur O. Friel serial and the conclusion of a Talbot Mundy two-parter, along with a W. C. Tuttle short story. It also sports an Ared White spy story and fiction by Andrew A Caffrey, William Edward Hayes, Capt. Frederick Moore and James Stevens. Are they so awful? I leave it to more experienced readers to tell us. Regardless, Adventure was humbled, but survived the humbling thanks to Popular Publication and survived as a still-respectable pulp until 1953, and even then it still survived, after a fashion, into the 1970s. The one thing you can say for certain was that as of this day in 1932, Adventure's best days were definitely behind it.

Sunday, August 14, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: August 14

This 1926 cover doesn't have the visual imagination of Western Story covers from 1939, but it has a simplicity and directness of design that makes it just as appealing. While the cover doesn't promote any of the authors in the issue, it has some familiar names inside. Frank Richardson Pierce returns to one of his first successful series characters with a tale of Flapjack Meehan. Pierce created Flapjack back in 1921 The novella "Flapjack Blows It Up" was the character's 43rd appearance as counted by the Fiction Mags Index, and the third Flapjack story of the year. From this point, however, Pierce began to lose interest; Flapjack would not appear again until November 1927, and then only five times more (including the serial Flapjack Meehan in Street & Smith's Far West Illustrated) over the next three years. Meanwhile, Robert Ormond Case introduces a new character -- or so we can safely assume, since all his stories bear his first name -- in Windy Delong. An aggressive attempt was made to put Windy over; he'd appear in two more novelettes in the next three weeks. The character appeared more sporadically thereafter; thrice in 1927, twice in 1928 and 1929; once in 1930 and 1931. He then showed up thrice more between 1934 and 1937. Frederick Faust has a serial running under his John Frederick alias, while Joseph B. Ames continues The Man From Wyoming. There's also a novelette by Harry Golden, who was actually Harold de Polo, and short stories by Harry Adler, Austen Hall and E. E. Harriman. The cover promises "Big Clean Stories of Western Life," which may or may not be a benefit depending on what you mean by "Clean."

Saturday, August 13, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: August 13

In 1927, after roughly a year and a half of existence, West celebrates its promotion from twice-a-month to weekly. Technically West switched to weekly on August 6, but I suppose this one's the first truly weekly issue in that it followed just one week after the previous number. The publisher couldn't maintain the punishing pace set by Street & Smith's Western Story and Wild West Weekly, however, and West relapsed to twice-a-month in November 1928. The noteworthy contributor this issue is R. R. Whitfield, better known as Raoul and best known for his stories, under his own name and as Ramon Dacolta, in the legendary hard-boiled pulp Black Mask. As with some other western pulps, for West at this time "western" was more a geographic than a chronological category. Hence Whitfield could publish "air patrol" stories here. He published five stories in West, but I leave it to the specialists to inform us whether all of these were air stories. The advertised star writer is Oscar J. Friend, whose Gun Harvest must have been bang-up stuff, since he really hadn't published enough to be advertised on the strength of his name. Maybe his sideline as a literary agent helped get him recognition here. Familiar oldtimers like Raymond S. Spears and Frank C. Robertson are also on hand, as are lesser-known names like Sig Young and T. von Ziekursch. West is supposed to be a pretty great western pulp but I haven't sampled one yet, though I'm increasingly tempted to do so.

Friday, August 12, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: August 12

Richard Case isn't quite on the level of H. W. Scott as a pulp cover artist, but I still like the concept of this 1939 Western Story cover. This particular issue is another twofer for Frank Richardson Pierce, who has a novella under his own name and a short story under his Seth Ranger alias. Among the contributors, E. C. Lincoln is the most unfamiliar to me. He'd been writing for Western Story since 1925, though his bibliography isn't as long as that time span would suggest. Lincoln published all of four stories from 1933-5 before picking up the pace again starting in 1936. 1939 was actually his busiest year since 1931, with nine stories appearing in Western Story. Like fellow contributor S. Omar Barker, Lincoln is best known today for his poetry rather than his prose. Jack Sterett and Bennett Foster round out the lineup of fiction writers this time out. I doubt whether August 12 was a Friday that year, but Case's cover is a good image for that day of the week.

Thursday, August 11, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: August 11

The August 11, 1934 Argosy is part of the unz.org online pulp trove. Cover story author Gordon MacCreagh specialized in African stories and went on a real safari there for Adventure in 1927. His Kingi Bwana series, also from Adventure, has been brought back into print by Altus Press. "Zimwi Crater" comes with all the racial baggage you'd expect from a pulp story set in Africa, particularly on the touchy subject of maintaining white "prestige," but it's still raw, thrilling pulp fiction. It's noteworthy as an early echo of the pop-culture impact of King Kong, which had been released the year before. The menace of the story is described as "an immense ape. Like that moving picture, Kong. Not that enormous, of course; but --" In practice, however, the "ogre" of the crater reminds me more of the hellacious ape-thing from the movie Tarzan, The Ape Man -- a monster I can't help but admire for the way he beats the stuffing out of Cheetah -- or was it proto-Cheetah? I lose track. Anyway, guilty or not, "Zimwi Crater" is a pulp pleasure. It was more entertaining than "The Honest Forger," a silly Gillian Hazeltine "complete novel" (35 pages) from George F. Worts. To be fair to Worts, I think he meant this one to be silly, but with the Hazeltine stories it's sometimes hard to tell. You also get one of H. H. Matteson's Aleutian island tales and a hillbilly crime story by Hapsburg Liebe, as well as serial chapters from Ray Cummings (sci-fi), Hulbert Footner (Madame Story) and Charles Alden Seltzer (western). Note that Seltzer is a big enough name that he only needs one name on the cover. This isn't an issue I would have bought but "Zimwi Crater" definitely makes it worth checking out.

Wednesday, August 10, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: August 10

Of the "big four" general-interest adventure pulps, Short Stories seems to have depended the most on series characters when promoting itself. You could argue that Argosy hyped its star characters as eagerly, but I don't recall seeing the venerable weekly beat its chest the way Short Stories does over having four popular recurring characters in this 1933 issue. It is a formidable lineup, even if you don't count W. C. Tuttle's Hooty McLoon, who doesn't even rate a mention as a series character in the Fiction Mags Index. Clarence Mulford's Hopalong Cassidy is clearly the star, and some people today may still recognize the name. But L. Patrick Greene's Major, the African diamond buyer -- always accompanied by his capable sidekick Jim the Hottentot -- is another pillar of pulp fiction, and James B. Hendryx's Corporal Downey may have been pulpdom's most popular "Northwest" character until Black John Smith and the denizens of Halfaday Creek took over Hendryx's spotlight. Meanwhile, Vincent Starett's Jimmy Lavender had been a Short Stories mainstay since 1922, though this issue would prove to be his last appearance in the twice-a-month magazine. And that's not all! You also get a serial chapter from Jackson Gregory, a sea story by B. E. Cook and the "Mandarin Dagger" novella by Lemuel de Bra that apparently justified reusing a classic Duncan McMillan yellow-peril cover from February 1932. You'd think that while you were trumpeting new stories with all these popular characters you'd spring for a new cover that might show one or two of them. But I guess Short Stories, which had broken Adventure by expanding to 224 pages the previous year and would maintain a relentless twice-a-month schedule until 1949, had to economize somewhere, sometime.

Tuesday, August 9, 2016

VINTAGE PAPERBACK OF THE WEEK: Peter Dawson, RENEGADE CANYON (1949-51)

When Fred Glidden discovered how easy it could be to get stories published in the pulps, he made pulp fiction a family business, first recruiting his wife, then his older brother Jonathan. Fred was "Luke Short," for a time probably the best-selling western author in the country. Mrs. Glidden was "Vic Elder," who published in the western romance pulps until motherhood took too much of her time. Jonathan became "Peter Dawson," publishing his first stories under that name in 1936, not long after Luke Short's pulp debut. By World War II Luke Short had made it into the slicks. Peter Dawson kept on plugging in the pulps and finally hit paydirt with Renegade Canyon. It was his first western serial for the most popular of slicks, The Saturday Evening Post, running concurrently with Dawson's Stirrup Boss in Short Stories. Like Brother Luke, Brother Pete could breathe life into cliched situations by writing fairly uncliched characters. Renegade Canyon has a great big cliche at its heart. The hero, Dan Gentry, is a cavalry officer who's just been court-martialed and thrown out of the army for a "criminal and foolhardy action" that cost numerous lives. Only he and his faithful Sgt. McIrishman -- all right, it's McCune -- know the truth, which is that Gentry is covering up for a dead brother officer who committed the real foul-up. In melodramatic fashion, Gentry is covering up and taking the blame because his beloved, dying commanding officer is the dead loser's dad and might die all the sooner if he knew the truth about his boy. Gentry will not attempt to vindicate himself until after Major Fitzhugh passes on, which makes the Widow Fitzhugh, the Major's daughter-in-law, inpatient. She knew that her husband was a bum and she has the hots for Gentry, so she can't stand playing the dutiful widow for long.

On his way to some sort of new life Gentry comes upon the wreck of a wagon train that had been sacked by Sour-Eye's Apache band. The scene has already been gone over by whites, but our hero finds what others missed: a living white woman hiding in a box. Her survival interferes with horse trader Caleb Ash's plans to claim the salvageable goods as his own, and her infatuation with Gentry interferes with the Widow Fitzhugh's plans for Dan. Dan's main concern is how the m.o. of this attack matches the raid that wiped out his men. He suspects that greedy Ash had a hand in both attacks. Caleb's main line is selling remounts to the cavalry at extortionate prices; the cavalry unit that was massacred was seeking out a new supplier. Gentry and Sgt. McIrishman -- this is really unfair of me, since Dawson gives McCune only the lightest of brogues -- suspect that Ash provided intel to Sour-Eye's band in order to consolidate his market share. Worse yet, Ash is questioning the massacre survivor's identity as Faith Tipton because that would interfere with his claim on the salvaged goods. Caleb Ash is a thoroughgoing villain, but one of the virtues of Renegade Canyon is the way Dawson has him think and mostly act like a human being rather than a stock pulp villain. Ash reminds me a lot of the villains you saw in Budd Boetticher's movies with Randolph Scott; people who are just trying to get ahead in life like everyone else, but have made wrong, ruthless choices that ultimately make them irredeemable. That approach actually makes for more formidable villains, compared to the brutish bullies of inferior pulp. It helps that Dawson is really good at writing suspenseful action scenes. The highlight here is a long sequence in which Gentry has to escape from Ash, an excellent marksman who has him trapped in the hills, by setting a brush fire in the hope that the smoke will hide him. Ash isn't so easily eluded, and the last chapters nicely maintain suspense by keeping the villain offstage, building up our anticipation for what our hero knows to be his inevitable reappearance. Canyon is a good-sized western at 197 paperback pages, but it reads well and definitely holds your interest. It's the first Dawson novel I've read and I'll probably read more if they're like this one.

Here's what you get at the end of the book: a list of other Dell titles then on sale and an endpaper showing off the different keyhole logos Dell used for its four main genres: adventure, mystery, romance and western.

THE PULP CALENDAR: August 9

Now that's a thrilling title. And yet Murray Leinster's serial The Man Who Feared is not the most eccentric (or, depending on perspective, most lame) title in this 1930 Detective Fiction Weekly. That honor, if you can call it that, must go to Erle Stanley Gardner's novelette "The Crime Waffle." I'd hoped that some reference work on Gardner might explain that one, but it must remain a mystery for now. This number also features "The Charlie Chaplin of Crooks" in a nonfiction article that begs the question in what respect can one be the Chaplin of crime? Are you comical? Are you shabbily dressed? Do you play for pathos, or are you an artistic genius? The answers lie within. On a more mundane level Judson P. Philips concludes the serial Mountain Murder (a fairly common pulp title), while Harold de Polo and Robert H. Rohde contribute short stories. DFW cover art at this time was already fairly stodgy, but with that Leinster title (and the fainting dame) this cover is positively soporific.

Monday, August 8, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: August 8

My 1936 Argosy collection is growing slowly but surely. It's practically virgin territory because unz.org had only one issue from that year -- the first, in fact -- in its pulp trove. There's plenty to get in 1936, but it'll be a more expensive year than either 1934 or 1935, where my collection has been concentrated so far. That's because Edgar Rice Burroughs returns to Argosy after a hiatus, L. Ron Hubbard begins to place stories regularly, and Robert E. Howard has a posthumous run of stories. For instance, I bought this issue because, along with novelettes by the dependable Donald Barr Chidsey and Robert Carse, is continues a four-parg serial by the also dependable Eustace L. Adams. I have the August 1 issue where Adams' Brave Men Die Hard begins but chose to break the Munsey monotony with a Dime Detective last week. The August 15 issue, with the third installment of the serial, might have proven more expensive than any Argosy I've bought to date because it contains Howard's "The Dead Remember." Fortunately, just a few weeks ago some kind person uploaded a scan of that issue for Yahoo's pulpscans newsgroup. That just leaves me August 22 to catch up with, and I don't think Johnston McCulley or even Cornell Woolrich command such prices as Howard does. But let's not get ahead of ourselves.

The cover this week is a little confusing to me, because the V. E. Pyles painting seems to be illustrating Bennett Foster's western serial Thief-Lover Valley (given the buckskin-clad hero) rather than Chidsey's "Battleship on a Mountain," though the more popular author's name is more prominently placed. "Battleship"is set in Haiti, which proves to have been a popular setting for pulp fiction, what with its violent history, its voodoo mythos and its provocative racial contest. Robert Carse had been there before and would return, but his base of operations this week is Indo-China. Foreign Legion specialists like Carse, Georges Surdez and J. D. Newsom arguably gave Americans their first hints, or perhaps first warnings, of what the Vietnam experience would be for any "imperialist" power. Pulp stories set there make for especially fascinating reading, though I haven't read this issue yet to judge Carse's effort. I did take enough of a look at Dale Clark's "The Devil in Hollywood" to satisfy myself that the title didn't refer to Clark's continuing character, the sleazy talent agent J. Edwin Bell. Instead, "Devil" appears to a genuine horror story rather than Clark's typical Hollywood comedy. As for the rest, I look forward to describing some of them in more detail in the future. I can say now that this issue of Argosy was sponsored by:

Sunday, August 7, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: August 7

During the years 1936-37 Donald Barr Chidsey was one of the dominant Argosy writers. He was on a particular tear in the summer of 1937, landing the cover three times in a two-month period. He specialized in fast-moving adventure tales in exotic settings and "Passage to Hong Kong" is typical of his output at the time. It's probably the best thing in this issue, which also includes a No-Shirt McGee south-western (the old sourdough got around!) by Frank Richardson Pierce and a Four Corners American gothic by Theodore Roscoe. The serials are Luke Short's King Colt, which wraps up this issue, John Hawkins' Strike and Arthur Leo Zagat's Drink We Deep, an exercise in the microscopic world subgenre of what were then called fantastics. Short stories by Berton E. Cook and William Corcoran round out a typically diverse issue from this era. Chidsey will return tomorrow in a 1936 issue from my own collection.

Saturday, August 6, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: August 6

Simon Templar makes his Detective Fiction Weekly debut in this 1938 issue. The great creation of Leslie Charteris first saw print in England a decade earlier and quickly became a mainstay of the British story paper The Thriller. The Saint made his American debut way back in 1930, in Clayton Publications' All Star Detective Stories. He didn't appear in an American pulp again until 1933, when "The Death Penalty" appeared in Star Detective Novels, from the publishers of Short Stories. Starting in 1934 he had a more prestigious perch in The American Magazine, a slick monthly from the publishers of Collier's. In 1937 he began appearing in Munsey pulps, first in the monthly Double Detective, then in DFW. Most of the magazines I've mentioned up to this point made a point of identifying the author on their covers, but not his creation. That DFW ballyhoos the presence of The Saint probably has something to do with the release of the first Saint movie by RKO Pictures a couple of months earlier.Templar would appear twice more in DFW, both times in March 1939, then once in the monthly Flynn's Detective Fiction after Popular Publications took over the title. The Saint eventually had his own digest magazine from 1953 to 1967. Apart from the Charteris story, this issue of DFW is notable for not having a serial running. I guess that makes this the ideal issue to sample, since you don't need any other issue to enjoy it in full. Unfortunately, it doesn't seem to have a top-flight lineup apart from Charteris; the other contributors are Thomas W. Duncan, Baynard Kendrick, Julius Long and Frederic F. Van de Water. I don't know enough about any of them to judge them, but The Saint is great stuff.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)