Adventures in a Golden Age of Storytelling by SAMUEL WILSON, Author of "Mondo 70," "The Think 3 Institute," etc.

Monday, February 29, 2016

PULP READING: Eustace L. Adams, "ANYWHERE BUT HERE," Part Three

From the tremendous February 23, 1935 issue of Argosy, here's the third and concluding installment of Eustace L. Adams's serial, Anywhere But Here. International, commercial and romantic intrigue all reach a climax amid a typical fictional Latin American revolt carried out in classic pulp style. If you've been following along week to week, click below for the conclusion.

And for those waiting to read the whole thing in one gulp, here's the complete serial in one convenient package:

THE PULP CALENDAR: February 29

When Adventure was publishing three times a month the third issue of the month usually was dated February 28. Since only one leap year fell within that period, this 1924 issue is the only Adventure to carry a Feb. 29 cover date. Robert Robinson contributes a fierce Yellow Peril cover though, as usual in this period, it probably doesn't illustrate one of the stories inside. The highlight for regular Adventure readers would be the latest exploit of Hashknife Hartley, W. C. Tuttle's most enduring cowboy detective. Another star writer, Arthur D. Howden-Smith, was taking a break from Swain the Viking and in the middle of a serial, Porto Bello Gold -- a prequel to Treasure Island and this the Black Sails of its day, but with the still-necessary permission of the Robert Louis Stevenson estate. William Byron Mowery, a specialist in Northwestern stories, and Gordon MacCreagh, who usually wrote African tales, have stories in this issue, while Bill Adams, who regularly contributed a "Slants on Life" column to the magazine, throws in a fiction story as well. The thrice-monthly period probably saw Adventure at its peak, so here's a salute to a typical issue on its 92nd -- or is it 23rd? -- birthday.

Sunday, February 28, 2016

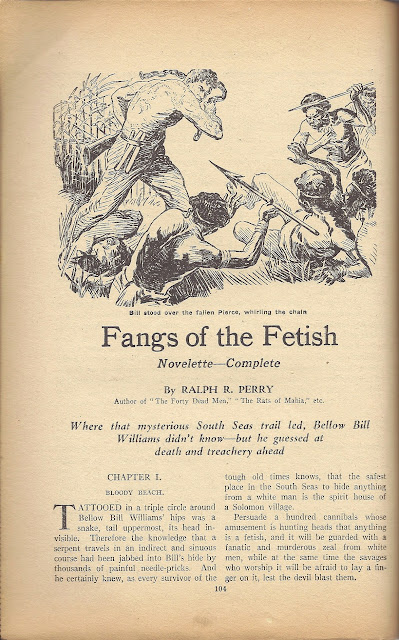

BELLOW BILL WILLIAMS in "FANGS OF THE FETISH"

The first Bellow Bill Williams story I paid to own is actually one of Ralph R. Perry's weaker efforts. That's because Perry as narrator gets a little too omniscient for his own good, warning readers in advance that Bill is putting his trust in the wrong man. He'd run to the rescue of an old-timer who was proving admirably cool while under attack by superior numbers, and while it's admirable of Perry to show how Bill's misjudgments can get him into trouble, it's better most of the time to show rather than tell. Also, while Perry at his best plots complex action at a breakneck place, "Fangs of the Fetish" is more concerned with sudden revelations about people and their pasts that bring the action to a halt. In it, Bill is convinced to help a man recover a plaque revered by savages as a powerful fetish because the plaque has information embedded in it that will help the man reclaim his rights from a former partner after years in prison. Too easily impressed by this man's coolness under fire, Bill eventually learns that he's the real villain who wants the information for blackmail purposes. From out of nowhere, virtually, emerge two new characters intimately tied to the family scandal that forms the basis for the blackmail plot. Bellow Bill forces a final test of manhood on all three characters, from which Perry draws an ambivalent moral about the capacity for courage even among the wicked. I suspect that Perry himself realized that he'd misfired here, because he slowed down after setting a blistering pace in 1934 and produced only two more Bellow Bill stories in 1935 (and only one more ever after that), those two being two of his best. Even this one still has some nice action sequences, and if you like the freebooting spirit of the South Sea sailor subgenre you should still find "Fangs" entertaining. Judge for yourself by downloading the 22 page novelette from the link below. In the months to come look for more Bellow Bill from my personal pulp collection on this blog.

ARGOSY, February 23, 1935.

THE PULP CALENDAR: February 28

By 1942 Street & Smith had strayed pretty far from their strikingly minimalist cover concepts of 1939. This Wild West Weekly cover, with what had become a standard white background, actually looks rather primitive. The focus on series characters remains consistent, of course. Kid Wolf had been kicking around since 1929, while James P. Webb's Blacky Solone was a more recent invention, dating back only to 1940. Of the other authors I know Gunnison Steele, a near-omnipresent writer of this era, and I recognize Rod Patterson's name without really having an impression of him yet. The most intriguing title this issue is Harvey Maddux's "Canteen of Death" while Patterson's "Crimson Wool and Other Green Hides" borders on the inscrutable for someone like me who remains a relative greenhorn.

Saturday, February 27, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: February 27

In its heyday, Street & Smith had three weekly "Story" magazines. Detective Story is considered the first detective pulp, though there were plenty of precursor detective dime-novel magazines. It may have been first, but it wasn't the best. Detective Story doesn't get the same love extended to Black Mask, Dime Detective or even Detective Fiction Weekly. I guess it missed out on or caught on very slowly with the hard-boiled trend. The canonical authors of the genre don't seem to have congregated there. The authors of this 1932 issue are completely unknown to me. That is a nice Yellow Peril cover by John A. Coughlin, however. For whatever reason, Detective Story didn't have the staying power of Street & Smith's other "Story" weeklies. While Love Story and Western Story maintained a weekly schedule all the way to 1943, Detective Story would lapse to biweekly before 1932 was over. It would go monthly in the fall of 1935 and stay that way for most of the duration. It was quarterly by the time Street & Smith killed most of its fiction mags in 1949.

Friday, February 26, 2016

BELLOW BILL WILLIAMS at UNZ.ORG

I discovered Ralph R. Perry's tattooed pearler amid the several dozen Argosy issues scanned and uploaded to Ron Unz's website, a mind-boggling trove of popular fiction in its original form. Along with a diverse selection of pulps in other genres, from Ranch Romances to Thrilling Wonder Stories, unz.org has a huge run of Collier's, "the National Weekly," the home of Fu Manchu and the magazine where many pulp authors found slick legitimacy. It's not exactly a balanced sample of pulp (no Adventure or Blue Book, not so much Short Stories) it's still one of the first places to go to read a lot of pulp stories. There are three Bellow Bill stories in the Unz collection; the links below will send you to the site's .pdf renderings, which can be downloaded for your reading convenience.

Bellow Bill is surprised to find an old blind man on his schooner who proves to be a legendary and honorable trader whose son has been kidnapped by an old enemy who rules the title island as "boss and witch doctor." The old man wants Bill to attempt to negotiate for the youth's release but mainly to try and rescue the lad, since the old-timer doesn't trust his enemy to honor any ransom deal. Bill finds his quarry inside a volcano and has the devil's time getting out to plan his ultimate rescue attempt. You'll feel like you've walked a mile of lava in Bill's shoes, and you'll wonder how he doesn't lose the fine-cut chewing tobacco he always keeps loose in his pants pocket. Intense physical action and a welcome attention to detail in characterization even for subordinate villains.

A preposterous academic quest draws Bellow Bill into a treasure hunt, but before he even gets started Bill is attacked by an antagonist big enough to impersonate him, with body paint substituting for Bill's famed tattoos. While he escapes his initial predicament he's subject to distrust from some of the treasure hunters so long as his doppelganger is on the loose. Mutual misunderstandings complicate the competition with the double and the man backing him. Perry emphasizes that Bill himself is an imperfect judge of character. His fallibility makes the stories more entertaining, since you can't necessarily guess how things will turn out from Bill's first impressions.

The penultimate Bellow Bill story is one of the best. In an eerie opening he discovers an abandoned ship with corpses in the captain's quarters, three of whom are islanders with luminescent paint on their faces, and only one of whom seems to have died by violence, though the captain had been tortured. The mystery takes him to an island ruled by "pirates without a ship" led by a missionary-educated native and his twin brothers. It's an unhappy commonplace of pulp that a little education only makes native types more dangerous, but Perry makes the pirate leader into a formidable antagonist, emphasizing a tactical genius that forces Bill to figure out an elaborate multipronged plan of attack requiring the aid of the dead captain's sister, her native servant, and a drunken, cowardly trader whom the pirates had maintained as a figurehead to lure fresh victims ashore. Perry can write action thrillers with the best of pulp authors, and these stories are the proof.

Bellow Bill is surprised to find an old blind man on his schooner who proves to be a legendary and honorable trader whose son has been kidnapped by an old enemy who rules the title island as "boss and witch doctor." The old man wants Bill to attempt to negotiate for the youth's release but mainly to try and rescue the lad, since the old-timer doesn't trust his enemy to honor any ransom deal. Bill finds his quarry inside a volcano and has the devil's time getting out to plan his ultimate rescue attempt. You'll feel like you've walked a mile of lava in Bill's shoes, and you'll wonder how he doesn't lose the fine-cut chewing tobacco he always keeps loose in his pants pocket. Intense physical action and a welcome attention to detail in characterization even for subordinate villains.

A preposterous academic quest draws Bellow Bill into a treasure hunt, but before he even gets started Bill is attacked by an antagonist big enough to impersonate him, with body paint substituting for Bill's famed tattoos. While he escapes his initial predicament he's subject to distrust from some of the treasure hunters so long as his doppelganger is on the loose. Mutual misunderstandings complicate the competition with the double and the man backing him. Perry emphasizes that Bill himself is an imperfect judge of character. His fallibility makes the stories more entertaining, since you can't necessarily guess how things will turn out from Bill's first impressions.

The penultimate Bellow Bill story is one of the best. In an eerie opening he discovers an abandoned ship with corpses in the captain's quarters, three of whom are islanders with luminescent paint on their faces, and only one of whom seems to have died by violence, though the captain had been tortured. The mystery takes him to an island ruled by "pirates without a ship" led by a missionary-educated native and his twin brothers. It's an unhappy commonplace of pulp that a little education only makes native types more dangerous, but Perry makes the pirate leader into a formidable antagonist, emphasizing a tactical genius that forces Bill to figure out an elaborate multipronged plan of attack requiring the aid of the dead captain's sister, her native servant, and a drunken, cowardly trader whom the pirates had maintained as a figurehead to lure fresh victims ashore. Perry can write action thrillers with the best of pulp authors, and these stories are the proof.

THE PULP CALENDAR: February 26

Better days at Detective Fiction Weekly: it's 1938 and the magazine is still 144 pages a week. Here's a nice cover with minimal copy advertising a genuinely decent sized "short novel" of 47 pages, apparently dealing with labor unrest, a hot topic during the Depression. Frederick C. Painton was a pretty good writer who started out in war and "war-air" pulps in the late 1920s. He broke into Argosy late in 1935, made it into Blue Book in June 1936 and made his DFW debut that October. By 1938 most of his stuff was appearing in Munsey mags, including his Argosy series about the globetrotting insurance investigator Dan Harden. He dabbled in "fantastics" a little for Argosy with his Time Detective series, but as the situation deteriorated at Munsey during 1941 he started publishing more in Short Stories and Blue Book, starting a series for the latter about the secret agent Jason Wyatt. He went to war as a correspondent and died of a heart attack on Guam in 1945. Norman A. Daniels and Frederick C. Davis probably are the best-known names among the other contributors. I know nothing about most of the contents but I'd say Painton's simple "Fink" is the best title in the table. Believe it or not, this was the fourth consecutive issue without a story by Richard Sale, but he'd be back with a Daffy Dill novelet the following week.

Thursday, February 25, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: February 25

An unusual cover design for a 1934 issue of Short Stories, clearly intended to highlight the variety of content to be found inside. I can't tell from the table of contents whether it accurately represents the contents of this particular issue; nothing listed really says "Foreign Legion" or "Yellow Peril" to me, for instance. You'll also notice a certain disproportion; there are two cowboys when they could have had, let's say, a deep sea diver, a polar explorer, a soldier, a safari dude or someone like the Major, etc. But there often seemed to be more western stuff in Short Stories than anything else. The headline writer this number is Clarence E. Mulford, who'd been writing Hopalong Cassidy stories since 1905. One year from this point, Hoppy would make his film debut, planting the seeds of a craze that would break out in the early days of television. Short Stories had been Hoppy's headquarters since 1926, but Mulford would take him elsewhere for a time, starting in 1935, before bringing the character for two final serials in 1937 and 1941. Erle Stanley Gardner, credited in the lower left-hand corner, had already created Perry Mason by this point but kept plugging away in the pulps. In February 1934 alone he had two stories in Detective Fiction Weekly, one in Argosy and one in Dell's All Detective besides this issue's "Lawless Waters." Cliff Farrell, a western specialist, is the best-known to me of the other contributors. You probably did come close to "action stories of every variety" in Short Stories, but since that was Argosy's motto, the cover artist (or editor) decided to show rather than tell.

Wednesday, February 24, 2016

BELLOW BILL WILLIAMS: a preliminary checklist

The tough American sailor working the South Seas is a pulp archetype. Gordon Young is credited with popularizing the type with his Hurricane Williams stories (and here's a Hurricane Williams novel) while the writer who made it his specialty more than any other, both in the pulps and the slicks, was probably Albert Richard Wetjen, whose Wallaby Jim, a Collier's hero, inspired a 1930s B movie. These South Sea stories are part seaborne westerns, part barbarian tales. They describe a largely lawless land where "savages," normally ruled by homegrown superstition, are easily lorded over by unscrupulous white exploiters, often with the aid of "witch doctors," while colonial overseers are far away. The heroes of these stories are the exceptional men, just as determined to make a living by trade, often as contemptuous toward natives as their villainous rivals, sometimes more alienated from their own cultures and "civilized" life, but always essentially moral and honorable. While villains seek to build little empires by oppressing natives and plundering resources, the heroic seamen often end up building empires of a kind by slaughtering these oppressors and plunderers, thus becoming recognized as laws unto themselves in the islands, men to whom victims and innocents can turn for aid and advice. These heroes of the South Seas flourished in a world with no recognizable geopolitical limits. their greatest antagonists being men much like themselves, or those men's savage allies. It wouldn't be the same for them to spend their time fighting Nazis or Japs, as some presumably did during World War II. A dream of independence, self-reliance and power redeemed by character would be lost. It may have been no accident, then, that Bellow Bill Williams passed from the scene in 1936, not long before the Axis powers to be began to hog all the villain action in pulps. While he sailed, Bellow Bill had some of the most colorful and violent adventures of any South Sea hero, and he probably was literally the most colorful of them all.

Now Bellow Bill Williams was six feet and three inches of bone and muscle. He weighed two hundred and forty pounds. If his voice was known through the South Seas, so was the amazing display of tattooing that covered every inch of his skin from hips to neck and shoulder to wrists. There was a full-rigged ship on his chest, a Chinese dragon on his back, bracelets of rope tattooed in pale blue ink around each wrist, and a snake coiled three times around his hips.

"The Golden Oyster" (1935)

Ralph R. Perry made sure to put such a descriptive paragraph into all his Bellow Bill stories. For the record, Bill is also blond, though Perry describes his hair as curly, unlike the illustration above from "Terror Island" (1933). Perry also made a point of reminding readers that "Bellow Bill was a rotten shot, perfectly capable of missing a man with all six bullets at any range greater than fifteen feet," as in "The Atoll of Flaming Men" (1935). It's a nice touch that makes Bill something less than a superman, though Perry emphasizes that his hero likes to get to close quarters where his superior strength will tell. Perry is very good at putting Bill in physical distress in empathetic fashion. Bellow Bill is implacable but not imperturbable; you can tell when he's scared or flustered, or when he recognizes that he's misjudged a person or situation. There's a nice sequence in "Atoll" in which Bill has to talk himself into going into the hold of an abandoned lugger after already seeing that it's dragging a corpse by an air hose, knowing he can find nothing good. Bellow Bill is a pearler by vocation, but in the stories I've read you never see him ply his trade. Instead, he acts as a troubleshooter or negotiator for others based on his reputation for honorable dealing and formidable strength. His good nature and sense of loyalty get him into awful jams; his cunning, determination and brute strength usually get him out of them, though in "Terror Island" the main villains are taken out by a faithful dog whose mysterious death signals one last death trap for our hero.

Not much seems to be known about Ralph R. Perry. A birth year of 1895 appears to be certain, but the date of his death is unknown. He served in the Navy during World War I and wrote a number of non-fiction articles about his experiences, placing one in the prestigious Atlantic Monthly in 1920. According to the Fiction Mags Index he started appearing in pulps in 1924. In fact, he started at the top in Adventure. His first Argosy story doesn't appear until 1929, by which time he had published frequently in Adventure, Short Stories and several western and sea pulps. He published two more short stories and a two-part serial in the venerable weekly that year. When Bellow Bill first appeared I don't yet know. The first time the character is mentioned on a cover is in the August 1, 1931 issue, but the very fact that "Missing" is identified as "A Bellow Bill Novelette" indicates that Perry's hero was already a known quantity to Argosy readers. A number of novelettes from 1931 or 1930 are candidates for the first Bellow Bill story until a more complete Argosy collector sets me straight. It's possible, of course, that Bill was tried out in Adventure or Short Stories before settling in for his long run at Argosy, since authors usually could move characters from pulp to pulp at their pleasure.

If we don't know yet when Bellow Bill begins, we can at least build considerably on the Fiction Mags Index's very limited listing of Bellow Bill stories. In its index of series characters, the Index identifies only two Bellow Bill stories, ignoring the three stories that have long been identifiable and available in the unz.org trove. Moving forward from "Missing," I submit my preliminary and sometimes speculative list of Bellow Bill Williams stories in Argosy:

"Missing," August 1, 1931.

"More Than Millions," December 26, 1931 -- from this point, I'm going to work on the assumption that a "South Seas novelette" by Perry is a Bellow Bill tale.

"The Stuff of Empire," July 9, 1932 (confirmed by Sai S. below)

"Cat's-Paw," September 17, 1932 - ?

"Fanged Harbor," January 7, 1933 - ?

"The Accomplice," July 22, 1933 - (confirmed by Sai S. below)

"Terror Island," October 7, 1933 (unz.org)

"Huascar's Treasure," January 6, 1934 - ?

"Jib-Boom Charlie," March 3, 1934 (verified from the previous issue's "Looking Ahead" feature)

"The Wrong Move," April 7, 1934 (verified by Fiction Mags Index; in my collection)

"The Scar," June 2, 1934 (verified by Fiction Mags Index; in my collection)

"The Jungle Master," July 14, 1934 (verified from previous issue's "Looking Ahead")

"Blood Payment," October 6, 1934 (in my collection)

"The Rats of Mahia," December 1, 1934 (in my collection)

"Fangs of the Fetish," February 23, 1935 (in my collection)

"The Golden Oyster," May 25, 1935 (unz.org)

"The Atoll of Flaming Men," October 19, 1935 (unz.org)

"Shark Trail," March 21, 1936 (in my collection).

After 1936 Perry concentrated on westerns, though his 1939 Argosy story "Shark's Treasure" comes close to the old flavor of South Seas mayhem. Ultimately, to make my case for Bellow Bill I have to show rather than tell, so later this week I'll upload my scan of "Fangs of the Fetish" and point you to the Bellow Bill stories in the unz.org trove, which has become trickier to negotiate recently than it used to be. You practically have to be a Bellow Bill of the computer to find your way around, but the pulp trove is worth the trip.

THE PULP CALENDAR: February 24

Still moving back in time with Detective Fiction Weekly, we reach 1940, at a point when Munsey was still commissioning cover paintings. This is a good one by Emmett Watson, presumably illustrating Judson P. Philips's Murder Is My Hobby, though the cover appears to be illustrating Suicide is My Hobby. The nearly omnipresent Richard Sale has a short story this issue, but DFW takes him for granted, not even listing his name on the cover. As for those on the cover, Paul Ernst was spending most of his time playing Kenneth Robeson for Street & Smith's The Avenger, while Roger Torrey shared his talent with DFW, Black Mask, and the "spicy" pulp Private Detective, and Myles Hudson continues his Blue Ghost serial. Maitland LeRoy Osborne, an old-time with only three stories to his credit in the Fiction Mags Index, contributes a short story, as does Kenneth Crossen under his Bennett Barlay pseudonym. When you could produce attention-grabbing covers like this one, why would you give up that ability? Times must have been tough at Munsey to make them give up on cover paintings later this year.

Tuesday, February 23, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: February 23

The February 23, 1935 Argosy is as loaded an issue as you're likely to see. For starters, it concludes Eustace L. Adams's serial Anywhere But Here, which I'll have ready for you to download later this week. And as Adams wraps up his story, George F. Worts launches a Singapore Sammy serial. Worts was one of Argosy's superstars in the first half of the Thirties, with Sammy and ace defense attorney Gillian Hazeltine being two of the pulp's most popular recurring characters, and that's not even counting his side gig as Loring Brent, the creator of Peter the Brazen. Singapore Sammy Shay is the best of Worts/Brent's creations: a slightly disreputable globetrotting treasure hunter with a grudge against his devious deadbeat dad. While Worts would close up the Loring Brent shop with a final Peter the Brazen novelet later in 1935, Sammy would get three serials, counting this one, over the next two years before his creator jumped to the slicks and got boring.

Now that I've covered the serials, let's see what else this issue has to offer.

Two top pulp hands introduce new characters this issue. "Spy Against Europe" is the first of three H. Bedford-Jones stories about a spy who comes to be known as The Sphinx. To be honest, I can understand why the series didn't last long after reading this one. More of a milestone is W. C. Tuttle's contribution, "Henry Goes Arizona." To explain the apparent illiteracy, one "goes Arizona," presumably, the way one "goes Hollywood." Henry, to introduce him fully, is Henry Harrison Conroy, a relic of vaudeville who finds himself heir to a ranch in Wild Horse Valley, Arizona. Dismissed as a dude and a drunk, and decried as "The Shame of Arizona," Henry's sardonic intelligence, and a little help from his eccentric new friends, always gets the better of the bad guys in the modern but still wild west. Perhaps the ultimate embodiment of Tuttle's specialty, the comic western detective story, Henry was an instant hit with Argosy readers, and proved popular enough to justify an M-G-M adaptation of this issue's origin story, only with Frank (Wizard of Oz) Morgan in the title role rather than the too-obvious W. C. Fields, though Fields alone, as both actor and writer, could have done the part real justice. Before 1935 was over Henry got his first Argosy cover, and from that point forward his red-nosed rotundity fronted any issue that started one of his serials. Henry survived the collapse and near-demise of Argosy by moving to Short Stories, where his adventures continued to the end of the 1940s.

While Henry's debut makes this an historic issue and the two serials are terrific, the true highlight this week, for me at least, is Ralph R. Perry's "Fangs of the Fetish," an appearance by my own favorite Argosy character, Bellow Bill Williams. I'll be spending a large part of this week proselytizing for Bellow Bill: scanning "Fangs" for your reading pleasure and linking you to other tales while compiling a preliminary checklist of the tattooed pearler's career that will expand greatly on the Fiction Mags Index's inventory. Argosy hardly gets more pulpy in the blood-and-thunder sense than when Bellow Bill roams the South Sea islands, as you'll find over the next few days.

Once I make the Adams and Perry stories available, most of the contents of this issue will accessible to non-collectors in one way or another, as the Bedford-Jones and Tuttle stories have recently been republished by indispensable pulp-fiction preservers Altus Press, while RadioArchives.com recently issued The Monster From the Lagoon in its entirety as an e-book. If I'm feeling generous I'll scan the Kenneth Gilbert and Frank Triem stories, one an animal story, the other a western short, so that pulp fans can collect a virtually complete issue of the venerable weekly from somewhere near the peak of its powers. For now, I leave you with a word from this issue's sponsor:

Monday, February 22, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: February 22

We've moved back in time approximately a year before yesterday's Calendar entry, to when Detective Fiction Weekly was still weekly. Like Argosy, DFW had seen its page size expand while its page count shrank in January 1941. Similarly as well, DFW had a nasty standard photomontage cover design which it actually had adopted well before Argosy did likewise and well before the size change. The top bar, red this week, changed color from issue to issue. There's still more fiction than fact at this point, counting Theodore Roscoe's presumably fact-based fiction, "The Grouch of Goree." Richard Sale is at the end of a streak this week; he had placed a story in every issue of DFW so far in 1941, eight in all. It seems fair to say that Sale was the magazine's star writer from the end of 1936, a year when he did most of his writing for Black Book Detective, until early 1942. The other genre heavy hitter this week is Cleve L. Adams, who continues his serial Decoy. There would be one more cover style change before DFW acquired the look you saw yesterday. You'll see what I'm talking about approximately two months from now.

Sunday, February 21, 2016

PULP READING: Eustace L. Adams, "ANYWHERE BUT HERE," Part Two

In old-time serial fashion, here's your weekly dose of Eustace L. Adams' 1935 Argosy serial Anywhere But Here, in which American aviators are embroiled in international intrigue in a fictional Central American country. Poor Al Burke has to worry about his kid sister and fellow flyer falling in love with his buddy Bat Gillespie, while Bat's old girlfriend from San Lorenzo starts to make moves on Al on the rebound. But as the illustration promises, Adams doesn't stint on the mayhem amid the romance. The concluding installment is part of an incredible Feb. 23 Argosy we'll peek at next Tuesday, and a few days later you'll be able to finish this story, or get the entire serial complete in one file. For those who can't wait for this week's episode, click on the link below and enjoy.

THE PULP CALENDAR: February 21

By 1942 the former Flynn's was no longer Detective Fiction Weekly. Like its Munsey stablemate, Argosy, Detective Fiction had gone biweekly in the fall of 1941. It wouldn't stay that way for long; with the April issue it would go monthly, limping towards oblivion until rescued, like Argosy, by Popular Publications at the end of the year. By this point, there isn't much detective fiction, either. Richard Sale and Lawrence Treat contribute short stories while James Edward Grant continues a serial, but the rest of the 66 page issue is true crime. The cover story counts as that, I suppose, but while we assume the Nazis capable of anything I suspect there may have been some exaggeration in this particular expose. There's a sad irony is this exploitatively crappy cover. Back in 1940, when DFW, like Argosy, did away with cover paintings in favor of a standard format, Munsey justified the move in part by claiming that the new covers were more tasteful. Clearly that appeal to taste had not reversed Munsey's plunging fortunes, so now the publisher tries for the opposite extreme. They were willing to pay painters again, but not, it seems, good ones. Still, this one doesn't look so bad compared to some of the atrocities Argosy produced in 1942. Whatever happened to once-mighty Munsey from roughly 1938 to this point is a cautionary tale I wish I knew more about. For now, most of it is a mystery to me.

Saturday, February 20, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: February 20

There are five issues of Adventure dated February 20, published between 1922 and 1926, when the magazine was coming out three times a month. None of the covers are really spectacular or weird, so how do I decide which one to put on the Calendar? It came down to which issue had the best lineup of writers, and this 1922 issue has the big two for small-a adventure fans, Harold Lamb and Talbot Mundy, with complete stories. On top of that, this number has two of Adventure's most popular western scribes, Hugh Pendexter (continuing a serial) and W. C. Tuttle. On top of that you have J. D. Newsom, an author I like very much, and five more stories by writers I'm less familiar with. The chances are that Charles Victor Fischer, E. E. Harriman, Harrison S. Howard, Robert Simpson and William Wells all had something going for them to make it into an Adventure from the magazine's golden age. You'd think the lion would be more excited!

Friday, February 19, 2016

VINTAGE PAPERBACK OF THE WEEK: Donald Hamiton, LINE OF FIRE (1955)

Donald Hamilton is best known as the creator of Matt Helm, a hard-boiled spy who was done a great disservice by the campy movies Dean Marin made in his name in the 1960s. I've only read one Helm book so far -- if I recall right it was The Removers -- but I liked it a lot. Line of Fire predates the Helm series by five years. It's a grim and gripping little affair. The back cover copy could hardly be more grim:

Hamilton's hero steps back from that abyss at the end -- the suicide passage is from the last two pages of the novel -- but Paul Nyquist's trouble begins when he doesn't kill a man. He isn't supposed to kill the man, who happens to be the Governor of the State. Instead, he's supposed to fire a near-miss so the Governor can say he's been under fire from the gangsters he's been fighting, when in fact he's in cahoots with the same gangsters -- or, to be specific, Paul's boss Carl Gunderman -- who've arranged this little show to give him political cover. The problem is that Paul, distracted by his mob escort, actually hits and wounds the governor. Worse, despite this being a Saturday a woman is in the building and finds the two arguing after the fact. Worse yet, when the mob guy decides he has to kill the woman, Paul kills him. Since Paul isn't going to kill her, despite her fears, he has to take her with him on the lam while he waits to see what Carl will do with him.

Paul and Carl have a conflicted relationship. Their bond formed on a hunting trip when Carl panicked at the sight of a wild board and Paul saved his life, at the cost of his manhood when the dying boar gores him. As a result, Carl trusts but distrusts him, knowing him to be dependable but knowing that he knows something damning about him in a personal if not a legal way.

To explain the nature of his injury to the woman, Barbara, he cites The Sun Also Rises:

"Did you ever read an old book by Hemingway? Ernest Hemingway? It's about a nymphomaniac, a Jew, a bullfighter and a character who was injured in a certain way. Well, I had a hunting accident once." I saw her eyes widen slightly. She did not move. I said, "It walks, it talks, it sleeps, it eats, it's practically human. It's capable of all normal activities, in fact, except one."

Paul announces this, after having hinted at it, after he has married Barbara in order to save her life, depending on the old trope of the wife being forbidden from testifying against her husband in a trial. He'd assured her earlier that "there will be ample grounds for divorce or annulment when the danger is past." Despite all this, you probably won't be surprised to learn that Paul and Barbara fall legitimately in love. It's when Paul thinks she's left for good, after all is over, and after he learns that Carl has killed himself, that he has his suicidal moment. Hamilton reverses course at the last moment."Who the hell are you trying to impress, anyway?" Carl asks himself. He's resolved to muddle through and is making breakfast when the happy ending happens. Until then, Line of Fire has been a bleakly introspective crime novel, grounded in Paul's knowledge of guns and other mundane details. It observes a certain gun fetish in the culture without quite sharing in it. Paul's life is saved at one point, after all, when a gunman who has the drop on him, with Paul's hands empty, invites him to a classic fast-draw shootout instead."Hopalong Cassidy wouldn't have liked it" otherwise, Paul observes, "Roy Rogers would have slapped his wrist. The Lone Ranger would have never spoken to him again." That sardonic attitude helps put Line of Fire over as an entertaining, engaging little novel (192 pages) of the kind they hardly make anymore. And to be fair to Hamilton, I wasn't sure whether he'd cop out in favor of a happy ending until that very last page. How happy is it, anyway, when the heroine says, before the final clinch, "It won't hurt any more five years from now than it does this morning....We may lose each other anyway, but it seems stupid not even to try." Fair enough.

THE PULP CALENDAR: February 19

A dynamic cover -- I don't recognize the artist and the Fiction Mags Index doesn't give a credit -- launches a new Borden Chase serial in this 1938 Argosy. It looks like Chase is dealing with police this time, though the dame in the circle might be mistaken for Smooth Kyle's girlfriend Gilda Garland. By my standards this issue has a strong lineup. Cover-billed Richard Wormser and Philip Ketchum are good writers, though I don't know whether Wormser's "Black Orchids Tonight" is a Dave McNally story or not. Ketchum's "Galleons for Panama" is clearly a period piece, but that was his specialty, as he would show the following year with his Bretwalda series about a magical axe and its owners across the centuries. Luke Short continues his Golden Acres serial while Jacland Marmur, a nautical specialist I discovered and enjoyed in the pages of Collier's, contributes a short story, "Typhoon Cardigan." Following in the steps of Joseph Conrad, Marmur was a Pole who made good writing in English. Among the lesser contributors is one Logan Ancram, whose "The Golden Glyphs" is his only known contribution to pulp fiction. What's more likely: that "Ancram" is a pseudonym or that someone only had one publishable story in him for his whole life? No matter; the authors I've mentioned would make this issue worth happening, though it'd prove pricey to collect Trouble Wagon in its five-part entirety, since the issue it wraps in has Tarzan on the cover. You'll see it soon enough.

Thursday, February 18, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: February 18

Another eye-catching cover design from Western Story in 1939. Norman Saunders did this one but I'm sure much of the credit goes to a Street & Smith art editor. Keeping the cover copy to a minimum keeps the potential reader focused on the cowboy in the gunsight. It certainly promises intense drama in the cover story, Tom Roan's "Funeral Mountain," even though Roan has never really made a strong impression on me. There's also a novelet by the questionably named Ney N. Geer --was that for real? The prolific Harry F Olmstead has a short story and the poet of the western pulps, S. Omar Barker, contributes some characteristic verse. Eugene R. Dutcher, Kenneth Gilbert and Jackson Gregory are the other fiction contributors. Dutcher's "Hate Rides Valley Pass" and Gilbert's "The Cunning of the Damned" are promising sounding titles, but "Funeral Mountain" has a stark simplicity, for a pulp title, that matches the dramatic simplicity of the cover design. Whether it's all good to read or not, it's definitely cool to look at.

Wednesday, February 17, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: February 17

Pulp readers often claimed to be embarrassed by the magazines they loved. They claimed to be embarrassed specifically by the magazine covers: too violent, too suggestive, too something. In our less straitlaced age it's hard to believe people could be ashamed to buy pulps in the store or read them in public, unless we mean the under-the-counter "spicy" mags or the more sadistic "shudder" pulps. But here's a 1934 Detective Fiction Weekly I can readily imagine embarrassing its regular readers. The cover story is the second appearance, according to the Fiction Mags Index, of Judson P. Philips' Park Avenue Hunt Club, who'd made their debut three weeks earlier and would return a month later. With highly-publicized supercriminals like John Dillinger running amok, highly organized rackets appearing to control whole cities, and a general fear of social breakdown during the Great Depression, vigilante fantasies were popular in the early Thirties, in movies as well as in the pulps. This is the era from which superheroes arose, after all. I can't speak for this story -- I don't think I've ever read any Hunt Club stuff -- but that cover may have been more embarrassing to a potential reader because it puts what looks in retrospect like an unflattering face on the vigilante fantasy, rendering it almost pornographic in its sadism. Today, a cover like this more likely means you'll pay more for this issue on the collectors' market. Apart from Edward Parrish Ware I don't know the other authors in this number, but that cover definitely does its job. You can't help but be curious, unless you're very easily revolted, about the story it illustrates.

Tuesday, February 16, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: February 16

You might assume that Foreign Legion stories are celebrations of imperialism, but usually they're more cynical than that, or too much concerned with the personal struggles and feuds within the Legion to worry much about the politics. J. D. Newsom was one of the top Foreign Legion writers, but in an autobiographical sketch contributed to this 1935 issue's "MenWho Make the Argosy" column, he makes his own worldview more clear.

Newsom sounds like no fan of either "hypotrophied nationalism" or the sort of imperialism that depended upon a Foreign Legion. "Grenades for the Colonel," on the other hand, takes a "natives can't be trusted" tack, as a disgraced Legion unit proves the only defense against a Moroccan uprising stirred up by a local demagogue who "had the same hold upon his people that some European dictators have acquired of late years in more civilized communities." This rabble-rouser stirs up some of the Legion's nominal allies, the Senegalese Tirailleurs, whom the rogue unit had earlier beaten up in a street brawl. It's not the best I've read from Newsom but it's entertaining enough. Despite the patriotic optimism he expresses above about America's potential for "a new form of civilization," Newsom would later in 1935 write a story about an American legionnaire in Indochina that in a way feels prophetic of things to come. He was just about done with pulps at this point and soon to be recruited for the Federal Writers Project, a New Deal program he would eventually lead. I find it interesting that a pulp writer would land such a job, but I suppose such a person would know all about lifting oneself out of poverty with a pen.

Let's see what else is in this issue:

By a comfortable margin, the serials are the highlights of this Argosy. Eustace L. Adams continues his kickass American-airmen-in-Latin America story Anywhere But Here, as you'll see for yourself shortly, while Frederick "George Challis aka Max Brand" Faust wraps up his second serial about Tizzo the Firebrand, The Great Betrayal. Best of the rest is Theodore Roscoe's satirical story "King for a Day," a sketch of the stressful life of a mitteleuropean monarch that all serves to set up a punch line about an American tourist dreaming of changing places with the ruler he doesn't recognize tending a garden. Just as Newsom invokes fascism faintly in his story, so Roscoe numbers Nazi Germany among his protagonist's many problems. Bits like these add contemporary color to the stories, but pulps had not yet taken a propagandistic or Popular Front turn. The goofiest story this week is easily Ray Cummings' fantastic, as Argosy called science fiction stories, "The Moon Plot." This look at the future from one of the pioneer sci-fi writers, who identifies himself as a 23rd century narrator, becomes instant camp when the defeat of a Martian plot to overthrow the government of the Moon hinges on a heroic girl disguising herself as not just a boy, but a Spanish boy, complete with the comic-strip accent, to win the confidence of a half-breed revolutionary. It's one of the few pulp stories I've read that I honestly find unintentionally hilarious. That leaves us with Allan Vaughan Elston's novelet "Badge of Honor," which builds up to the hero telling a noble lie to a small boy about the boy's father, Richard Howells Watkins' auto-racing story "Two Seconds Slow," and a little bit of torture pulp from William Merriam Rouse, "The Golden Fawn." Adams, Challis, Newsom and Roscoe make this issue worth having, but next week's issue, I think, is even better. Nevertheless, this issue of Argosy is brought to you by...

Monday, February 15, 2016

PULP READING: Eustace L. Adams, ANYWHERE BUT HERE pt.1

From my battered but unbroken February 9, 1935 issue of Argosy, here's the first of three installments of Eustace L. Adams's serial Anywhere But Here. Check out my Feb. 9 Pulp Calendar piece for more info about the story. Adams was a wartime flier -- publicity placed him with the legendary Lafayette Esquadrille -- whose main gig was a series of aviation adventures for kids featuring Andy Lane. Pulps were his adult writing and he rose to the occasion with crisp action-adventure tales that are part hard-boiled and a little part Lost Generation in their world-weary attitude. Adams broke into Argosy in 1928 and, apart from flying pulps, that remained his main pulp market, with Short Stories running a distant second. He also wrote for such slicks as The American Magazine, a monthly from the makers of Collier's, and Cosmopolitan when it was more fiction-oriented than it is today.

This is a good-sized, thirty-page opening installment graced with the spot illustrations of the main characters with which Argosy broke up the monotony of text in 1934 and 1935 -- an enhancement it made no sense to abandon. Rest assured that I own the February 16 and 23 issues, so as long as they're cooperative you can expect to get the complete three-part serial if this installment gets you interested. Begin now this combination bromance and romance in turbulent Central America by clicking the link below:

This is a good-sized, thirty-page opening installment graced with the spot illustrations of the main characters with which Argosy broke up the monotony of text in 1934 and 1935 -- an enhancement it made no sense to abandon. Rest assured that I own the February 16 and 23 issues, so as long as they're cooperative you can expect to get the complete three-part serial if this installment gets you interested. Begin now this combination bromance and romance in turbulent Central America by clicking the link below:

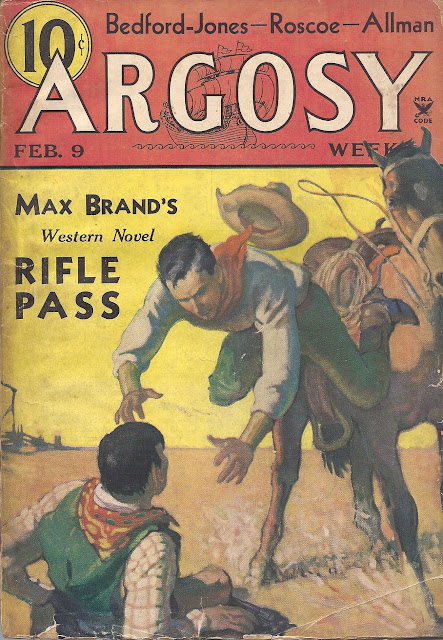

ARGOSY, February 9, 1935

THE PULP CALENDAR: February 15

That's a beautiful cover by Edgar Franklin Wittmark from a 1930 Adventure. I have no clue what the cover story, H. Bedford-Jones's "Jewels For a Lady," is about, but it's safe to guess that an Adventure cover story is Bedford-Jones in top form. The so-called "King of the Pulps" spread the wealth around the four major adventure pulps, with Blue Book getting the most, with plenty to go around for other magazines. Two other heavy hitters this issue are Arthur O. Friel, who starts a two-parter, and Thomson Burtis, who most often did airborne crime-fighting stories but worked other genres as well. Bill Adams, who has a fiction piece this issue, was virtually Adventure's house philosopher during the 1920s, when his non-fiction "Slants on Life" appeared regularly. Redvers' Cry Havoc!, introduced so dramatically on last issue's cover, wraps up this time, while E. S. Dellinger, Henry LaCossitt, Edmund M. Littell and Barry Lyndon round out the fiction lineup. Adventure is supposed to be past its prime by this point, but on an issue-to-issue basis I doubt any rival could top it yet.

Sunday, February 14, 2016

PULP READING: Sidney Herschel Small, "THE GLOVE OF THE FOX," BLUE BOOK, September 1935

If the Sidney Herschel Small story I linked you to the other day gave you an appetite for more, or if you're interested in freebooting adventures in 1930s China, here's the one and only Small story I own in its original pulp form. As of 1935 pulp stories set in China had not yet taking a propagandistic turn. Sure, the Japanese are bad guys, but in this period it's hard to find a good guy in China. No one was obligated to treat Chiang Kai-shek as one, for instance. China stories thus could take a hard-boiled, almost amoral tone, if not a "plague on all your houses" attitude toward the brutal factions vying for the country.

In this story, Red Carson and his rugged Mongol sidekick encounter a "Red" warlord -- interestingly, Small describes his villain as a "theoretical" Red, as if he's only playing Communist for convenience -- while trying to rescue some Christian missionaries. This is a startlingly grim story, in which the hero allows an innocent white woman to be poisoned in order to persuade the villain to take poison himself, and tells the victim's bereaved husband that she's better off, since she'd been driven mad by the atrocities she's witnessed.

If you download the story you'll see why Blue Book had a reputation as the best illustrated pulp magazine. Other publishers were often stingy with illustration, but Blue Book was lavish with art from the likes of John Richard Flanagan, who contributed a couple of double-page spreads to the Small story. I've put the September 1935 cover at the front of the file so you can get the full impact of those spreads if you go to two-page mode. "Glove of the Fox" is a brisk 11 pager and the first of more to come from this issue of Blue Book. Look for more Pulp Reading scans in the days to come.

In this story, Red Carson and his rugged Mongol sidekick encounter a "Red" warlord -- interestingly, Small describes his villain as a "theoretical" Red, as if he's only playing Communist for convenience -- while trying to rescue some Christian missionaries. This is a startlingly grim story, in which the hero allows an innocent white woman to be poisoned in order to persuade the villain to take poison himself, and tells the victim's bereaved husband that she's better off, since she'd been driven mad by the atrocities she's witnessed.

If you download the story you'll see why Blue Book had a reputation as the best illustrated pulp magazine. Other publishers were often stingy with illustration, but Blue Book was lavish with art from the likes of John Richard Flanagan, who contributed a couple of double-page spreads to the Small story. I've put the September 1935 cover at the front of the file so you can get the full impact of those spreads if you go to two-page mode. "Glove of the Fox" is a brisk 11 pager and the first of more to come from this issue of Blue Book. Look for more Pulp Reading scans in the days to come.

Blue Book, September 1935

THE PULP CALENDAR: February 14

Not every Asian on a pulp cover is the Yellow Peril. This fellow, for instance, is more likely defending his own land against a White Peril in the form of Jimmie Cordie and his merry band of American mercenaries, whom I presume to be the heroes of W. Wirt's serial The Guns of The American. Even if this isn't a Cordie story I've enjoyed everything by Wirt I've read so far. The enigmatic Wirt -- I still don't know what the first W stands for -- headlines what looks like a mighty 1931 issue of Argosy. Not only are two of my regular favorites, Frank Richardson Pierce and Ralph R. Perry, inside this week, and not only does Theodore Roscoe have a novelet, but the incredible Frederick Nebel makes what seems to be his only appearance ever in Argosy. Nebel is probably the best writer from the Black Mask stable after the canonized Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler. There's an emotional intensity in his hard-boiled stories of cops, detectives and reporters, a fury directed at crooks and crooked cops alike, that no other pulp writer I know of can match. I'm not sure what genre "The Creed of Sergeant Bone" falls into, but I suspect the story will kick ass, since everything pulp I've read from Nebel has done that. Tragically, Nebel himself didn't appreciate his gift. He seemed happy to write boring stuff for the slicks from about 1937 on and didn't care to see his pulp stuff reprinted. Sometimes writers themselves don't realize how good they are. That's probably more true for the pulps, where every writer presumably is conscious of writing by the word for the money, than anything else. As for this pulp, it's an issue I'd definitely like to own some day.

Saturday, February 13, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: February 13

This is Jimmy Wentworth. In the past year, Sidney Herschel Small published eleven of Wentworth's adventures in Detective Fiction Weekly. He ended up writing thirty Wentworth stories, though only four after 1933. You can read one of those stories here. This same week Small, who'd been publishing regularly in pulps since 1923, cracked the slicks with a story in Collier's, where he became a mainstay for the rest of the decade. Small specialized in East-West encounters, stories of whites in Asia or, as in the Wentworth stories, in an American Chinatown. I've read more of his Collier's stuff than his pulp work, and he ended up becoming one of my favorite writers for "The National Weekly." A number of Collier's writers crossed back and forth regularly from slick to pulp: Albert Richard Wetjen, Jacland Marmur and Georges Surdez are some of the others. But back to DFW: a more venerable series character appearing this issue is George Allan England's T. Ashley, who came to life in Street & Smith's Detective Story in 1922, lasted less than a year there, and returned to sporadic life starting in 1927. From 1931 until England's death in 1936 the character appeared in DFW exclusively. Among the other contributors are DFW stalwart Judson Philips, who wraps up a three-part serial, and Robert Speyder Case, whose serial The Fifth Man, which begins this week, is his only known pulp work. I didn't pick this issue for today because I thought the cover was that great, though it's probably the most dynamic February 13 cover out there, but because I wanted another chance to recommend Sidney Herschel Small to fans of adventure fiction. But since some of his stuff is back in print these days, I may be preaching to the converted.

Friday, February 12, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: February 12

The Fiction Mags Index doesn't give us the contents of this 1938 issue of Argosy, but several booksellers do. While Argosy doesn't follow the Collier's practice of putting Abraham Lincoln on its cover on this week in February every year, you'll see that the venerable weekly honors Old Abe's birthday with a story by Richard Sale. At this time Sale was doing a lot of Civil War stories for Argosy, along with the occasional Civil War-inspired Twilight Zone-style story set in the modern day. The other novelet this week is the cover story, Richard Howell Watkins's "Salvage Tide." Edgar Rice Burroughs wraps up Carson of Venus while Luke Short continues Golden Acres, but chances are that the best thing in this issue is the Georges Surdez short story, "The Coat of M'sieu Picart." Apart from these big names, Garnett Radcliffe continues his serial, London Skies Are Falling Down, while William Chamberlain, Philip Ketchum, Robert E. Pinkerton and James Lockette Hill contribute short stories. As usual in this period, Stookie Allen draws a page or two on the subject of "Men of Daring," this week honoring "Con Colleano -- Wire Wizard." Argosy was still 144 pages every week at this point -- it would slip to 128 pages later this year -- and this issue looks like a typically thick and possibly rich package of fiction.

Thursday, February 11, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: February 11

What would a Pulp Calendar be without at least one appearance of the Yellow Peril? Orientals fascinated pulp writers and readers. The problem with the way pulp portrayed Asians was that they went to opposite extremes, portraying them either as gibbering morons, usually as comedy relief, or (and usually more often) as sinister sadists. There was an alluring ambiguity to the pulp Oriental, since pulp never seemed quite as certain of Asians' inferiority as they were about other racial groups. But pulp was still just as racist towards Asians as it often was toward other groups because writers rarely imagined an ordinary guy or dame who just happened to be Asian. The whole point of having an Asian in your story, most of the time, was to indulge in fantasies of Otherness, which in the case of Asians often meant fantasies of setting aside American morality and getting away with murder, as often happens in stories set in Chinatown in which the murderer is the hero, if only because he kills someone even worse, as in the works of Walter C. Brown or Arden X. Pangborn. One can go too far the other way, of course, in refusing to imagine the possibility of Otherness on the assumption that people everywhere are essentially the same in all ways that count. That approach can result in a certain blandness of pop fiction, and in the meantime our fantasies of Otherness have been transferred to the paranormal ghettos of so many fictional cities, where vampires, werewolves, faeries and others play the roles for 21st century readers that the archetypal Chinaman played for our grandparents and great-grandparents. Once it became bad form to define people by Otherness, while people still dreamed and fantasized about it, Otherness had to become literally inhuman in order to endure in print.

I assume that this 1939 DFW cover illustrates the Norbert Davis story, though the title, "Ideal For Murder," gives away nothing. More interesting for me would be the Richard Sale novelet, "Guns For Spain." Pulp regarded the Spanish Civil War with some ambivalence, since it pitted fascists against leftists. Depending on how threatened an author felt by the Germans and Italians, one could take a "plague on both your houses" approach to the conflict, allowing maximum freedom of action for a freebooting hero. I'd be interested in seeing Sale's angle on the war, even though this story may well take place entirely outside Spain. Along with these featured stories, Judson Philips wraps up a serial and William R. Cox, a writer I identify with westerns, contributes a short story, as do Robert Arthur, William E. Brandon and one E. O. Umsted. The Fiction Mags Index doesn't give a cover credit but I like the tastefully lurid look of the thing. It isn't barking mad looking like the horror pulps of the period, but it still says "pulp" to me.

Wednesday, February 10, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: February 10

Here's a Short Stories from 1932, spotlighting a Foreign Legion novel, apparently set in China, by one of the genre's masters, J. D. Newsom. I'll have more to say about Newsom when I show you my Feb. 16, 1935 Argosy, but let me assure you that giving him the cover story probably makes this Short Stories worth getting all by itself. Notice how the cover copy emphasizes the globetrotting scope of the magazine's contents. Sometimes Short Stories is too heavy on westerns, but that's not the case here. Among the other authors R. V. Gery,who has a novelet, and Sinclair Gluck, who's in the middle of a serial, are solid if not top-tier writers. This is an ambitious period for the twice-monthly pulp. Little more than a month from this date, Short Stories would expand to a whopping 224 pages, making it bigger than the 192 page Adventure. At the end of August, Short Stories retreated back to its previous 176 page size, but at that same time Adventure suddenly shrunk by half, to 96 pages; it went monthly the following year. If the Short Stories plan had been to break Adventure by intensifying their biweekly competition at the trough of the Depression, it seems to have worked. Short Stories stayed "Twice a Month" until 1949.

Tuesday, February 9, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: February 9

This 1935 Argosy is one of the rattier items in my pulp collection. I acquired it in part because it has a chapter of one of George Challis's Firebrand serials, but mainly because it had the opening installment of another serial, Eustace L. Adams's Anywhere But Here. Adams was an action writer who more or less specialized in aviation stories, though he could do without the flying quite nicely. Anywhere But Here is a buddy story about two fliers who cut quite a swath through Latin America back in the day, having helped out with a revolution or two. Al Burke and Bat Gillespie had had enough of soldiering-of-fortune and had moved to New York, only to be dragged back to the nation of San Lorenzo, whose president they'd helped to install, to look after an American company's interests that are being challenged by French and German rivals. Complicating matters are Al's kid sister Mickey, now a famous aviatrix in her own right, who to Al's alarm is falling in love with Bat, and Carmencita, a San Lorenzo lady over whom Al and Bat had been romantic rivals in the past. These are all hard-living, hard-drinking, hard-boiled folks, for all the romance that develops, and Adams strikes just the right tone for this sort of story. I've liked a lot of what I've read from Adams and I may do you a favor and scan the serial into a little novel you'll all probably enjoy. But let's look at what else is inside this issue:

As was often the case in this period, Frederick Faust has multiple stories in an Argosy, including the Challis serial and the cover story under his most famous pseudonym. Max Brand's "Rifle Pass" is a meandering "complete novel" of 36 pages in which a sheriff's underachieving son is deputized in order to pressure him into proving himself by catching a notorious outlaw. The son has skills but hardly seems to give a damn about anything, and is soon suspected of turning outlaw himself. Western fans can probably figure where this is headed but it's a fair page-turner just the same.

As for the rest, Faust's great rival for productivity, H. Bedford-Jones, contributes a short story about his old series character, the Cockney detective John Solomon, while Theodore Roscoe's "He Floats Through the Air" is a grim little circus story about a paranoid aerialist. H. H. Matteson's "Perils Loose on Memamloose" is a comical tale of the Aleutians in which a white man's awful cornet playing stirs up the natives, and Jack Allman's "High Rigger" is a standard, readable lumberjack story. This issue covers a lot of territory and all of it feels like pulp rather than rejects from the slicks like a lot of latter-day Argosy. I'm not the most knowledgeable Argosy fan but my feeling is that 1935 saw the venerable weekly at its peak. I plan to submit more evidence for this claim over the next few Tuesdays. There are 23 1935 Argosy issues in the unz.org trove so feel free to explore for yourself before coming back here for more.

As was often the case in this period, Frederick Faust has multiple stories in an Argosy, including the Challis serial and the cover story under his most famous pseudonym. Max Brand's "Rifle Pass" is a meandering "complete novel" of 36 pages in which a sheriff's underachieving son is deputized in order to pressure him into proving himself by catching a notorious outlaw. The son has skills but hardly seems to give a damn about anything, and is soon suspected of turning outlaw himself. Western fans can probably figure where this is headed but it's a fair page-turner just the same.

As for the rest, Faust's great rival for productivity, H. Bedford-Jones, contributes a short story about his old series character, the Cockney detective John Solomon, while Theodore Roscoe's "He Floats Through the Air" is a grim little circus story about a paranoid aerialist. H. H. Matteson's "Perils Loose on Memamloose" is a comical tale of the Aleutians in which a white man's awful cornet playing stirs up the natives, and Jack Allman's "High Rigger" is a standard, readable lumberjack story. This issue covers a lot of territory and all of it feels like pulp rather than rejects from the slicks like a lot of latter-day Argosy. I'm not the most knowledgeable Argosy fan but my feeling is that 1935 saw the venerable weekly at its peak. I plan to submit more evidence for this claim over the next few Tuesdays. There are 23 1935 Argosy issues in the unz.org trove so feel free to explore for yourself before coming back here for more.

This issue of Argosy is sponsored by:

Monday, February 8, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: February 8

Another dynamic H. W. Scott cover catches the eye for this 1941 issue of Western Story. The main attraction inside is a 40+ page Walt Coburn novelet. The famed "cowboy author" would become omnipresent once Western Story went monthly in 1944, but at this point you could still go three or four weeks at a time without seeing Coburn. That matters because by some point in the Forties Coburn was past his prime. I've read some stuff of his from the late Forties that borders on the incoherent, but "Montana Rep" is closer in time to some still-decent stories he wrote for Argosy in 1940. William Colt MacDonald, creator of the Three Mesquiteers, one of whom was played by John Wayne when the Duke was still paying his dues, has a serial in this number. Harry F. Olmstead is probably the best known of the other authors this week. I think I'd prefer something from Popular Publications in this period, but Street & Smith's covers make their westerns look more attractive at first glance.

Sunday, February 7, 2016

From My Collection: BLUE BOOK, September 1935

Blue Book probably was always the classiest of pulp magazines. It certainly was the most lavishly illustrated. Its cover stock seems to be thicker than that of most pulps, and the page edges are trimmed to eliminate the rough edges and overhangs typical of pulp. Blue Book was published by the McCall company as a companion to Redbook, which then was much more fiction-oriented than it is today. It defied the dwindling trend of many rival pulps. While this 144 page 1935 issue represents a reduction in size from 160 pages earlier in the decade, the magazine would expand dramatically to 192 pages in 1939. Blue Book went bedsheet in September 1941, and if you still want to call it a pulp at that point, then it became probably the most beautiful pulp ever produced. If the bedsheet Argosy of 1941 metamorphosed into a moth, then Blue Book was Mothra. It helped to have an unmatched stable of interior illustrators -- not to mention iron man cover artist Herbert Morton Stoops, who moonlighted inside as Jeremy Cannon -- some of whose work you'll see as I begin to scan stories from this issue. Speaking of that, what have we to choose from?

Blue Book was unafraid to credit writers with more than one story per issue. One of their star writers, William Makin, scores twice this time with two series characters, the British Intelligence agent known as the Red Wolf of Arabia and the gypsy detective Isaac Heron. H. Bedford-Jones didn't like to see his name more than once on a contents page, no matter what Blue Book's policy was. That doesn't matter here since this is a Jones-lite issue by Blue Book standards. In a good month -- for him -- you might see stories under his most popular aliases, Gordon Keyne and Michael Gallister. A Bedford-Jones series might range all over history in search of tales to fit his theme of the moment. However prolific he was, you could depend on his for variety and solid story construction. Another Blue Book star, Robert R, Mill, starts a new series about G-Men this issue. He was best known for his more enduring series about "Tiny" David, a New York State Trooper who proved more clever than his oafish appearance suggested. From 1935 to 1938, Blue Book's flagship writer was William L. Chester, their in-house Edgar Rice Burroughs. Blue Book and Argosy competed for Burroughs stories constantly, and this issue announces a Tarzan story for the next issue, but Burroughs was flighty and pricey. Chester gave them a secure twist on the Tarzan formula with Kioga of the Wilderness, a white youth raised in a lost Native American tribe in the far north who had increasingly fantastical adventures during Chester's meteoric career.

As for the rest of this issue's contributors, I discovered Sidney Herschel Small through his Collier's stories in the unz.org trove. His specialty was the adventures of white people in Asia or in American Chinatowns. While they may not be "politically correct" by current standards, Small's stories were far less offensive than a lot of pulp chinoiserie, and they're usually crisply entertaining. Short novel contributor Leland Jamieson wrote a series of adventures about Coast Guard fliers, and "The Pirate of Vaca Lagoon" is quite a good one, as well as numerous flying stories before dying way too young of pancreatic cancer in 1941. William MacLeod Raine was a western writer whose career dated back to the 19th century and continued into the early 1950s. "The Triple Flip" is the first and only Blue Book appearance by Laurence Jordan, who published about a dozen stories overall in the first half of the 1930s. The "Prize Stories of Real Experience" are usually pretty entertaining, too, whether the stories were real or not.

To my mind, Blue Book sometimes got a little too high-toned or Anglomaniacal for its own good, but true pulp was always close to the surface, and you'll see some samples of what I mean in the near future as I scan stories from September 1935 for your convenience. Until then, this issue of Blue Book was brought to you by...

Blue Book was unafraid to credit writers with more than one story per issue. One of their star writers, William Makin, scores twice this time with two series characters, the British Intelligence agent known as the Red Wolf of Arabia and the gypsy detective Isaac Heron. H. Bedford-Jones didn't like to see his name more than once on a contents page, no matter what Blue Book's policy was. That doesn't matter here since this is a Jones-lite issue by Blue Book standards. In a good month -- for him -- you might see stories under his most popular aliases, Gordon Keyne and Michael Gallister. A Bedford-Jones series might range all over history in search of tales to fit his theme of the moment. However prolific he was, you could depend on his for variety and solid story construction. Another Blue Book star, Robert R, Mill, starts a new series about G-Men this issue. He was best known for his more enduring series about "Tiny" David, a New York State Trooper who proved more clever than his oafish appearance suggested. From 1935 to 1938, Blue Book's flagship writer was William L. Chester, their in-house Edgar Rice Burroughs. Blue Book and Argosy competed for Burroughs stories constantly, and this issue announces a Tarzan story for the next issue, but Burroughs was flighty and pricey. Chester gave them a secure twist on the Tarzan formula with Kioga of the Wilderness, a white youth raised in a lost Native American tribe in the far north who had increasingly fantastical adventures during Chester's meteoric career.

As for the rest of this issue's contributors, I discovered Sidney Herschel Small through his Collier's stories in the unz.org trove. His specialty was the adventures of white people in Asia or in American Chinatowns. While they may not be "politically correct" by current standards, Small's stories were far less offensive than a lot of pulp chinoiserie, and they're usually crisply entertaining. Short novel contributor Leland Jamieson wrote a series of adventures about Coast Guard fliers, and "The Pirate of Vaca Lagoon" is quite a good one, as well as numerous flying stories before dying way too young of pancreatic cancer in 1941. William MacLeod Raine was a western writer whose career dated back to the 19th century and continued into the early 1950s. "The Triple Flip" is the first and only Blue Book appearance by Laurence Jordan, who published about a dozen stories overall in the first half of the 1930s. The "Prize Stories of Real Experience" are usually pretty entertaining, too, whether the stories were real or not.

To my mind, Blue Book sometimes got a little too high-toned or Anglomaniacal for its own good, but true pulp was always close to the surface, and you'll see some samples of what I mean in the near future as I scan stories from September 1935 for your convenience. Until then, this issue of Blue Book was brought to you by...

THE PULP CALENDAR: February 7

Paul Stahr's cover isn't the most dynamic Argosy has run, but it rightly calls attention to one of Robert Carse's Foreign Legion stories. Foreign Legion is one of my favorite pulp genres (and you can find many samples of it at this blog), and while Georges Surdez is the undisputed master of that genre it's a close race, as far as I'm concerned, between Carse and J. D. Newsom for runner-up. Carse was just great at tough stories of endurance under stress; he could do prison or Devil's Island stories just as well. Until he started to get romantic and propagandistic at the end of the 1930s, Carse could hardly do wrong, and one of his novelets will likely put an Argosy or other pulp on my shopping list. This one is in the middle of a Frank Richardson Pierce serial, which probably is another plus, and another serial featuring J. U. Geisy and Junius B. Smith's Semi-Dual, a Persian occult investigator whose adventures had been appearing since 1912. Ralph Milne Farley wraps up yet another serial while William Corcoran starts a two-parter, The Death Ride, and gets a self-profile in the occasional "Men Who Make the Argosy" column. Lt. John Hopper, James Perley Hughes, Harold Bradley Say and John H. Thompson contribute short stories. I'm not sure if that adds up to "Action Stories of Every Variety," but it probably comes quite close.

Saturday, February 6, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: February 6

There's nothing about this 1943 issue of Wild West Weekly except that it's the last weekly issue. Going into 1943, Street & Smith still had three weekly titles: Wild West, its more mature stablemate Western Story, and its flagship romance title Love Story. They had outlasted Munsey's rival weeklies by more than a year, but wartime paper needs, I presume, put the kibosh on pulp weeklies for good. All three weeklies carried the same publication date. Western Story put out one more weekly issue on February 13, but it's unclear from the Fiction Mags index when Love Story's last weekly number appeared. The westerns then went on hiatus for the rest of February. Wild West's first biweekly issue has a March 13 cover date, followed by Western Story on March 20. Western Story would continue until Street & Smith wiped out most of its pulp line in 1949, but this was the beginning of the end for Wild West. It became a monthly in September and the November 1943 issue was its last. Western Story, converted to digest format, continued on a biweekly schedule until February 1944 before going monthly. The Feb. 6 Wild West Weekly features two series characters, Chuck Martin's Rawhide Runyan, a recent arrival who first saw print in 1938, and Paul S. Powers's Johnny Forty-Five, credited to Andrew A. Griffin, who dated back to 1930. Familiar authors Lee Bond, Hapsburg Liebe and Walker A. Tompkins also have stories in this milestone issue. Our ancestors were a mighty breed of reader to keep up with the weeklies and even the biweeklies of pulp's golden age, or else they simply had fewer alternatives or distractions. In some ways I envy them.

Friday, February 5, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: February 5

Nice move, Argosy. This 1938 cover lists five authors on the cover but forgets the guy who wrote the cover story. If I see animals and a man with a movie camera on an Argosy cover I say to myself, "That's Dave McNally." So I look at this cover and I ask myself, "Where's Richard Wormser?" Sure enough, Wormer has a McNally novelet, "The Singing Cats of Siam," inside. McNally must have been pretty popular, since we've seen him already this year, when our Calendar began. Not to acknowledge Wormser was either an error or a slap in the face, but it didn't stop him from submitting McNally stories, or Argosy from publishing them. In any event, Wormser needn't have felt overly slighted, since Edgar Rice Burroughs didn't make the cover, either, for the fifth chapter of his Carson of Venus serial.

I wonder how many browsers first assumed that L. G. Blochman wrote the story about the cameraman and the cats. His actual contribution was "Money for Sale," which could have been about anything. Blochman wrote a lot of stories set in Asia, but he also translated mysteries by Georges Simenon and others from French to English for American markets. The other cover-billed authors are known quantities, with Elston the least impressive to me. Richard Sale's story has one of those formulaic pulp titles from the period: "X Had a Y," in this case "Perseus Had a Helmet." Why this particular formula was so popular I can't say. Cornell Woolrich's contribution is "Wild Bill Hiccup," likely not one of the suspense master's finest or most suspenseful hours. The Wormser and the Blochman would probably make up for that.

Thursday, February 4, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: February 4

Another stark 1939 cover from the Street & Smith western pulps. Most of the names inside aren't familiar to me this time. Cover-billed Jackson Gregory was an old-timer of nearly thirty years in the business by this point, but I don't immediately recall reading anything by him, since I prefer my western pulps from a period after Gregory died. The one contributor I do know is Peter Dawson. I also know his secret identity. Jonathan H. Glidden was the older brother (by one year) of Frederick Glidden. Fred had broken into the pulps in 1935, taking as his handle the name of a famous gunfighter, Luke Short. His quick success inspired Short to convince not only his wife but his brother John to get into the racket. As Peter Dawson, John started placing stories in 1936. Apart from Dawson, most of the contributors are veterans whose careers dated back to the 1920s, though none went as far back as Gregory. It's with the next generation of western writers, contemporaries of the Gliddens or younger, that I really get interested in the genre, but I have no reason to doubt whether any of these older writers are good. Pulp is a matter of taste, after all. Those 1939 covers have such a modernist vibe, however, that to see old-timey writers inside might be disappointing. Those who've actually read these magazines will know better, of course.

Wednesday, February 3, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: February 3

The Blue Ghost may have been intended as Detective Fiction Weekly's answer to the Green Lama, who had become the star of Munsey's monthly Double Detective magazine. Nothing much became of Myles Hudson's creation, however, or of Hudson. The Ghost debuted in a five-part serial that begins in this 1940 issue, then rematerialized in November for another serial that apparently ended Hudson's pulp career -- presuming that Hudson was something other than someone else's pen name. Too bad, really; the Ghost looks like he wields a mean life preserver. Maybe he'll get it over the dame's shoulders before she can swing that axe. I presume so, since as noted the Ghost did get another serial. Then again, if he's a Ghost already what has he to worry about?