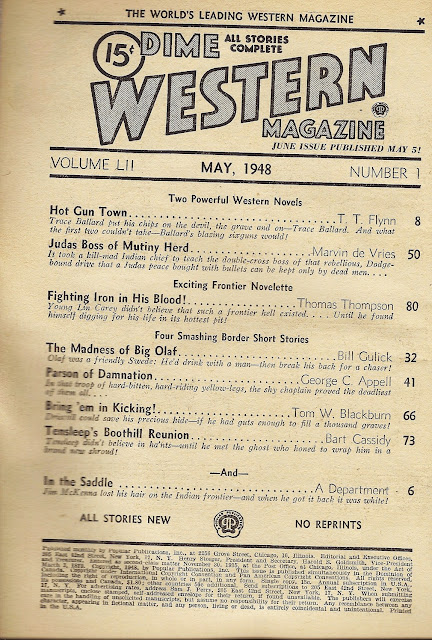

After posting individual stories from my copy of Dime Western for May 1948, I've finally completed my first cover-to-cover scan of a pulp magazine. Compared to many scanners out there, my resources are very limited. I use an HP C309 printer-scanner and the photo enhancement software that comes with it and Windows. After years of happily downloading incredible stuff from the Yahoo Pulpscans group, however, I decided that I had no more excuses for not doing my part to preserve the pulp heritage. Since Dime Western at this time was only 100 pages long, counting the covers, I set myself a relatively easy goal. Still, you'd be surprised at how hard it is to align a page just right, especially if your magazine is still intact, and how many botched scans had to go to the Recycle Bin. Finally, I have something complete with the cover coming up as your thumbnail the way it should. Let's review the contents once more:

You have major genre authors in Flynn and Thompson on top of the good short stories I'd downloaded earlier. The file downloadable from the link below is 100 MB. Like the story files, it's in the CBZ format, which is just a glorified .zip file in readable form. If you have Calibre's free text-conversion software you can turn this magazine into whatever file format suits you best. Enjoy this issue of Dime Western for posterity with my compliments. Click on the link below to begin:

Adventures in a Golden Age of Storytelling by SAMUEL WILSON, Author of "Mondo 70," "The Think 3 Institute," etc.

Sunday, January 31, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: January 31

Our first month ends with a Western Story from 1942. The cover design is a little more conservative than a few years earlier but that's still a nice painting by H.W. Scott. It's hard to be much more specific about the contents than "Action Stories of Fighting Courage." Top-billed Kenneth Gilbert starts a serial, Son of Storm King, this week, while the unbilled but decent L. L. Foreman wraps his serial, The Renegade. Mojave Lloyd is some sort of mystery man; the Fiction Mags Index is unsure whether the name was a pseudonym or not, and it does sound a little too western to be true. Harry F. Olmsted and Johnston McCulley are among the old reliables this issue, while Tom W. Blackburn is a younger reliable whose stories I've enjoyed fairly consistently. I'm working on the complete cover-to-cover scan of Dime Western for May 1948 so I'll be short here, but come back in February for another month of pulps!

Saturday, January 30, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: January 30

Today's cover story, from a 1937 Argosy, is a kind of crossover between the venerable weekly and its Munsey stablemate Detective Fiction Weekly. Nick Fisher and Eddie Savoy -- one a detective, the other a reformed thief -- were regulars in Argosy itself, while the police duo of Morton and McGarvey usually showed up in DFW. Pulp authors sometimes suggested that their various creations lived in a "shared universe." Pulps could even cross over with slicks if an author felt like it. I remember a story in the Wallaby Jim series Albert Richard Wetjen wrote for Collier's in which several other tough sea captains Wetjen had created for the pulps put in cameo appearances. I don't think I've read any Morton and McGarvey but I have read several Fisher-Savoys and they're pretty good. While Ace of Emeralds is part one of two, this issue also offers a Dave McNally novelet by Richard Wormser, another obvious plus, and short stories by such dependables as Gordon MacCreagh, Frederick Painton and Frank Richardson Pierce. Edgar Rice Burroughs and western writer Bennett Foster continue serials as well. This looks like a good issue to have from what may have been Argosy's last great year, though the Burroughs means you may pay more for it than you really want.

Friday, January 29, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: January 29

Daffy Dill was Richard Sale's most popular series character. Dill, a reporter, first appeared in Detective Fiction Weekly in the fall of 1934. This issue is from 1938 and features the 27th Dill story by the reckoning of the Fiction Mags Index. Sale would more than double that number before the series ended in 1943. I regret to say I haven't read any Dill stories, though I have one reprinted (in facsimile form) in the Hard-Boiled Dames anthology, since Dill had a resourceful sidekick in Dinah Mason. There's something nearly surreal in cover artist Vernon E. Pyles's juxtaposition of blind man, dog, dagger and the Hiawatha reference; what has all this to do with that? This is nearly an archetypal issue of DFW when you throw in the latest chapter of Judson Philips's Park Avenue Hunt Club serial. A less enduring series hero, Edgar Franklin's Johnny Dolan, also puts in a late appearance. Franklin wrote 19 Dolan stories in little more than two years, and "Them Cards Don't Lie" is the first of four from 1938 that wrapped up the series. William E. Barrett and Weston Hill contribute novelets, while Wyatt Blassingame, Samuel Taylor and Lawrence Treat deliver short stories. Evan Lewis's Davy Crockett's Almanack blog has scanned a number of Daffy Dill stories, though not this day's tale. You can check them out here.

Thursday, January 28, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: January 28

There's something peculiar about this 1939 Argosy cover. Look it over for a moment. Does something seem missing? Look at nearly any other Argosy and its cover will most likely promote the title of one of its stories. This issue only offers generic descriptions of its three big novelets: hockey novelet (Judson P. Philips's "Skate, You Sinners"); Civil War novelet (Richard Sale's "Him and General Lee"); adventure novelet (the third installment of Cornell Woolrich's anthology serial The Eye of Doom). A big headline for any one of them probably would have put more energy into this G. J. Rozen cover. Relatively unusual, also, is Argosy's failure to promote this week's new serial, but that might be explained, if the Fiction Mags Index is correct, by the new serial, George W. Ogden's Steamboat Gold, being an old serial, a reprint from the All-Story Weekly circa 1918. Short stories by Weed Dickinson, Nard Jones and Alexander Key, and the latest chapter of Edgar Rice Burroughs's Synthetic Men of Mars round out the issue. Hard to believe as it may be, but sports pulps were a popular genre for a long time, dating back to the dime-novel exploits of Frank Merriwell. I don't know if sports pulp stories are worth anyone's attention, other than Robert E. Howard's boxing stories, but Argosy would put sports on its cover about three or four times a year, mostly illustrating stories by Philips. He probably has little to do with this issue's collector value, which probably has everything to do with Burroughs and Woolrich, whose presence makes this number probably more pricey than it's actually worth.

Wednesday, January 27, 2016

VINTAGE PAPERBACK OF THE WEEK: Richard Telfair, THE BLOODY MEDALLION (1959)

The blurb from Sax Rohmer, who died the year The Bloody Medallion was published, doesn't seem to match the cheesecake scene on the cover, although the painting does illustrate a scene in the novel. Rohmer was being generous -- and how "terrifying" did people find his stuff even back in 1959? -- but Medallion, which began a series of five novels featuring American spy Montgomery Nash, is a grim little story. My copy is a 1966 reprint -- towards the back it advertises a novelization by Robert W. Krepps of that year's remake of Stagecoach, as well as the latest novel in Edward S. Aarons' more enduring spy series about Sam Durrell -- so even though the Nash series was over by 1962 the spy craze inspired by the James Bond movies presumably kept these novels in print. Telfair was a pen name for Richard Jessup, who created the alias for his Wyoming Jones series of westerns for Fawcett Gold Medal. Under his own name, Jessup may be best known as the author of The Cincinnati Kid, the source novel for the 1965 Steve McQueen film.

The Bloody Medallion is standard spy material with an extra ratchet or two of paranoia. It threatens to bog itself down in jargon early as Monty Nash, narrating his own story, describes his work for the Department of Counter Intelligence. He and Paul Austin are a two-man "first squad" that conducts "pursuits" of enemy agents abroad. His problem is that Austin disappears, and is reported dead, after giving Nash an urgent message. Austin was having an affair with a woman he met during a pursuit in Belgium, and Nash's superiors suspect that she flipped Austin. That puts Nash himself under suspicion. In time-hallowed fashion Monty has to fight his way out of headquarters so he can prove his innocence, if not his buddy's as well. The most interesting touch in the opening chapters is Nash's subjection to "narcosynthesis" by his superiors, who talk to him like he was a child ("Isn't Paul wicked to become a defector and traitor?") while trying to loosen his lips. After that Medallion becomes pretty old-fashioned stuff.

Nash makes his way to Belgium to interrogate Helga, the woman Paul was sleeping with. He discovers, after killing her husband and maid, that she's a member of the oft-rumored "medallion society," a sort of freelance communist international. "Even the Secret Police do not know who we are," she tells Monty. It all started with a band of teenage soldiers at the Battle of Stalingrad who swore to avenge the slaughter of their comrades by the Nazis. Nothing wrong with that, but postwar they resolved to fight fascists everywhere on earth, on the understanding that fascists are "all that stood in the way of socialist progress." In practice, anyone who stood in the way of socialist progress was a fascist. That put the medallion society on the path of enmity toward "the only real friends the Russian people ever had," i.e. the U.S. and its allies. Helga kills herself before Nash makes her give away names and places, but with the few clues available he tries to crack the society, taking another victim's medallion and exploiting the society's isolated cell structure to pass himself off as a member on his own mission. Against the odds, he is accepted by a unit that orders him to rob a Madrid bank. While dodging DCI squads pursuing him, Monty falls in love with Maria, a young Spanish woman with two vicious dogs -- that's her on the cover -- who's fallen into the society's orbit. His goal is to identify a real leader of the society and eventually take the whole shebang apart, but his prove to be Pyrrhic victories at best....

Monty Nash is a committed Cold Warrior, convinced that he's fighting, as a DCI man, for his own freedom."I think of myself as much too cynical to admit to any such simple dedication as fighting in my own way for the specific right to be a free man," he says, "Yet, in any honest self-examination, it must come down to that. There is no substitute for freedom." Yet Medallion is more pro-freedom than anti-communist, insofar as it doesn't demonize Nash's antagonists. Monty can recognize honor in some of his foes. "I can argue with what you fought for," he tells one such foe, who turns into an ally at the end of the story, but "I can't argue with a man who has fought well -- and lost." He later describes the same man as "the tired old revolutionary who had fought wisely, well, with courage and convictions." The point really is to contrast this revolutionary with the novel's real villain, who proves to be in it, and behind it all, purely for the money. Medallion gains a certain gravitas as it turns tragic at the end but the infiltration, romance and caper plotlines are all pretty commonplace. Despite all the talk about freedom and communism, the same story probably could have been told in Sax Rohmer's heyday. It's good enough to be a page-turner, and for the $1.50 I paid for it I suppose that's all right.

THE PULP CALENDAR: January 27

There's only one thing you can say about this 1940 cover: that was a close shave! And that's practically the only thing I can say about this issue of Western Story, which I picked for today only because it had the most interesting cover of any pulp with this day on the Calendar. Veteran western writers dominate this number, including cover author W. Ryerson Johnson, Harry Sinclair Drago and Gunnison Steele. Seth Ranger's in the middle of the serial that began back on January 13, and it's unusual to see him in an issue without his alter ego Frank Richardson Pierce contributing something, too. All these writers I've at least heard of; I can't really say that about short story contributors George Cory Franklin and Joseph F. Hook. At this point in 1940 Western Story gave you the same number of pages per week as Argosy, but that wouldn't last much longer. Argosy would soon shrink to 112 pages while Western Story kept putting out 128 pages a week for another three years.

Tuesday, January 26, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: January 26

I only see one man of murder on this 1929 cover -- if that's what he is -- but to be fair to the cover artist Edgar Wallace's serial was just getting started, and maybe the other men of murder would show up in subsequent weeks. Wallace was one of the most popular crime-story writers on Earth through much of the twentieth century. He was so popular in Germany, for instance, that a whole genre of film, the krimi, was inspired by Wallace's work thirty years after his death in 1932. Besides his urban crime stories, Wallace was known for his jungle tales of Commissioner Sanders (aka Sanders of the River), and as a co-creator of King Kong. He was popular enough in the U.S., where he died after moving to Hollywood, to appear in pulps and slicks simultaneously. Detective Fiction Weekly shared him with Street & Smith's Detective Story Magazine and the slick weekly Collier's (also the stamping ground of Sax Rohmer) at this time. While Wallace is obviously the main attraction here, a short story by the mysterious W. Wirt -- does anyone know what the W. stood for, or whether Wirt was male or female? -- is a bonus. Wirt was the creator of Jimmie Cordie, the leader of a motley band of bickering, bantering adventurers who are arguably the precursors of everyone from Doc Savage's amazing crew to Buffy the Vampire Slayer's Scooby Gang. Cordie's rampaging adventures in the Orient were a popular yet divisive series, appearing mostly in Argosy, where some readers found the body counts absurd. There'll be more about Cordie and his gang in due time, but Wirt also produced some hard-boiled crime stuff, of which this issue's "The Baron and I" may be a sample. Most of the other authors, apart from Edward Parrish Ware, are unknown to me, but the man in the top hat, mask and gun makes a strong case for this issue, don't you think?

Monday, January 25, 2016

75 YEARS AGO IN THE ARGOSY: January 25, 1941

This is the second "bedsheet" issue of Argosy after the venerable weekly's latest format change in an increasingly desperate sequence. Blue Book would take a similar leap later in the summer of 1941, and Argosy probably showed the folks at the McCall company what not to do. As noted one week ago, the photo collage cover format is hideous. Inside doesn't look much better. Blue Book became, if anything, only more beautiful than it already was when it went bedsheet with its September issue; key to that was the monthly's pre-existing policy of lavish illustration from a whole stable of artists, with multiple illustrations for each story. Argosy gave you one picture on each story's title page -- except for a brief period around 1934-5 when you got spot illos of the main characters in some of the stories -- and that left the 1941 reader facing brutal walls of tiny three-column type on most pages. This issue exists in dowloadable form online and I read it on an e-reader with a 7" screen. It wasn't pretty. Worse, it looks they simply blew up illustrations intended for the magazine's smaller size, and not to the artist's advantage, while they didn't blow up Stookie Allen's one page "Men of Daring" cartoon feature at all -- perhaps he objected -- surrounding it with wide, bare margins.

Since the Fiction Mags Index doesn't list this issue's contents, here's my contribution to pulp scholarship.

Argosy turned to one of its legendary characters to help put over the new format. Johnston McCulley's Zorro first appeared in Argosy's sibling pulp, the All-Story Weekly, in 1919. The prolific pulpster didn't do much with his creation until Douglas Fairbanks brought Zorro to cinematic life. He didn't really make an industry of Zorro until he most likely could sell little else late in his career. The vast majority of Zorro stories appeared on a nearly-monthly basis in the Thrilling group's West between 1944 and 1951. Earlier, after a 1922 serial McCulley didn't return to Zorro until 1931. Between then and 1941 there were two novellas, a short story and a serial. Throughout that period, however, McCulley published a lot of serials set in what Argosy called "Zorro-land:" Spanish-ruled California in roughly the same period as Don Diego Vega's career. These are often entertaining, probably because McCulley had the freedom to experiment with character, within certain generic parameters.

By comparison, the first chapter of The Sign of Zorro seems inert. That may be because it finds Don Diego in a funk. He hasn't worn the costume in some time, and has been mourning for his original beloved, whom we learn died of a fever. His father has to goad Diego into resuming his swashbuckling career when the Vegas learn what we discovered first-hand earlier, that a wealthy young woman is being menaced by a villain whose "reputation stinks like the wind blowing across a dead whale." Diego then does little more than interview the woman, with the first real action reserved for the next installment. McCulley is clearly more interested in other characters, particularly a retired pirate in whom the woman confides, and who in turn informs Diego's old servant Bernardo -- who has been cured of his muteness, we learn -- about her request for Zorro's help. In continuity, it's widely understood or believed that Don Diego is Zorro, but enough time has passed since the hero's last exploit that many have come to doubt the fact. Diego's disinterested benevolence in this opening installment doesn't give us much of a hook, and Diego himself seems bland compared to all the duelling dons McCulley had invented through the Thirties. There may have been fresh interest in Zorro due to the 1940 Tyrone Power Mark of Zorro remake, but Sign isn't as strong a lead as Argosy wanted or needed at this point.

Instead, and to no real surprise for pulp buffs, the best story in this issue is the "short novel" by Georges Surdez. The king of Foreign Legion stories, which means the master of hard-boiled colonial military adventures, Surdez owns a footnote in popular culture as the putative popularizer of the deadly game of Russian Roulette, which he described in a 1937 story for Collier's, one of the "slick" weeklies all pulpsters aspired to appear in. "No Medals for Heroes" deals with the regular French army in its darkest hour, during the German blitzkrieg of 1940. Surdez was Swiss by birth and wrote for pulps in English but obviously identified culturally with France. "No Medals" captures the rage and recrimination rife in defeat and the urge to blame it all on espionage, while giving Surdez's heroes a chance at payback as a handful of fliers wreaks havoc with a German bomber squadron. There's an ironic echo in Surdez's own impulse to blame "Fifth Column" elements for the Fall of France of Germany's own "stab in the back" myth of the end of World War I, and for once the irony is probably lost on the author, who nevertheless invests the adventure with his characteristic grim intensity.

The best of the rest is Jim Kjelgarrd's modern-western short story "Good Leather," in which an elderly lawman tries to pay an old debt to a dead friend by helping his outlaw son. Its happy ending is a kind of cop out but Kjelgaard strikes a sharp note portraying his hero's mortal despair as he thinks he's guessed wrong about the kid. I have nothing to say about Bennett Foster's serial Thunder Hoofs, which concludes this week, because Argosy almost never included recaps with the final chapters of their serials, leaving me no way to get into the story. Richard Sale's second chapter of Design for Valor does get a recap -- Argosy always invited browsers to "start now" with Part Two -- but this by-the-numbers wartime stuff had little to offer. "Mr. Emerson Please Copy" is an odd piece of Americana with obvious slick ambitions from Frank Bunce, purporting to tell the story behind Ralph Waldo Emerson's aphorism about consistency being the hobgoblin of small minds by inventing a name-dropping correspondent for the philosopher who goes west with plans for a utopian community but acquires more practical pioneer values. There's nothing really wrong with the story except that it hardly seems like the stuff of pulp, which was often the problem with Argosy at this time. Finally, the larger size allows Argosy to offer short-short stories complete on one page, just like Collier's, and this issue's short-short, Ken Crossen's "The Bowmen of Mons," reads like wartime propaganda before we got into the war. It's a heroic French resistance story with German occupiers under attack by the legendary title figure, whose real identity is supposed to surprise us. World War II hurt the pulps, I feel, because an all-encompassing Manichean struggle of that sort limits the options of pulp heroes who are more properly freebooters or freelancers. But the war was only one of Argosy's problems, and none of them were going to be solved with this makeover.

If anyone wants to judge this issue for himself or herself, here's a link to a digital scan you can download for use on your favorite reading device:

Since the Fiction Mags Index doesn't list this issue's contents, here's my contribution to pulp scholarship.

Argosy turned to one of its legendary characters to help put over the new format. Johnston McCulley's Zorro first appeared in Argosy's sibling pulp, the All-Story Weekly, in 1919. The prolific pulpster didn't do much with his creation until Douglas Fairbanks brought Zorro to cinematic life. He didn't really make an industry of Zorro until he most likely could sell little else late in his career. The vast majority of Zorro stories appeared on a nearly-monthly basis in the Thrilling group's West between 1944 and 1951. Earlier, after a 1922 serial McCulley didn't return to Zorro until 1931. Between then and 1941 there were two novellas, a short story and a serial. Throughout that period, however, McCulley published a lot of serials set in what Argosy called "Zorro-land:" Spanish-ruled California in roughly the same period as Don Diego Vega's career. These are often entertaining, probably because McCulley had the freedom to experiment with character, within certain generic parameters.

By comparison, the first chapter of The Sign of Zorro seems inert. That may be because it finds Don Diego in a funk. He hasn't worn the costume in some time, and has been mourning for his original beloved, whom we learn died of a fever. His father has to goad Diego into resuming his swashbuckling career when the Vegas learn what we discovered first-hand earlier, that a wealthy young woman is being menaced by a villain whose "reputation stinks like the wind blowing across a dead whale." Diego then does little more than interview the woman, with the first real action reserved for the next installment. McCulley is clearly more interested in other characters, particularly a retired pirate in whom the woman confides, and who in turn informs Diego's old servant Bernardo -- who has been cured of his muteness, we learn -- about her request for Zorro's help. In continuity, it's widely understood or believed that Don Diego is Zorro, but enough time has passed since the hero's last exploit that many have come to doubt the fact. Diego's disinterested benevolence in this opening installment doesn't give us much of a hook, and Diego himself seems bland compared to all the duelling dons McCulley had invented through the Thirties. There may have been fresh interest in Zorro due to the 1940 Tyrone Power Mark of Zorro remake, but Sign isn't as strong a lead as Argosy wanted or needed at this point.

Instead, and to no real surprise for pulp buffs, the best story in this issue is the "short novel" by Georges Surdez. The king of Foreign Legion stories, which means the master of hard-boiled colonial military adventures, Surdez owns a footnote in popular culture as the putative popularizer of the deadly game of Russian Roulette, which he described in a 1937 story for Collier's, one of the "slick" weeklies all pulpsters aspired to appear in. "No Medals for Heroes" deals with the regular French army in its darkest hour, during the German blitzkrieg of 1940. Surdez was Swiss by birth and wrote for pulps in English but obviously identified culturally with France. "No Medals" captures the rage and recrimination rife in defeat and the urge to blame it all on espionage, while giving Surdez's heroes a chance at payback as a handful of fliers wreaks havoc with a German bomber squadron. There's an ironic echo in Surdez's own impulse to blame "Fifth Column" elements for the Fall of France of Germany's own "stab in the back" myth of the end of World War I, and for once the irony is probably lost on the author, who nevertheless invests the adventure with his characteristic grim intensity.

The best of the rest is Jim Kjelgarrd's modern-western short story "Good Leather," in which an elderly lawman tries to pay an old debt to a dead friend by helping his outlaw son. Its happy ending is a kind of cop out but Kjelgaard strikes a sharp note portraying his hero's mortal despair as he thinks he's guessed wrong about the kid. I have nothing to say about Bennett Foster's serial Thunder Hoofs, which concludes this week, because Argosy almost never included recaps with the final chapters of their serials, leaving me no way to get into the story. Richard Sale's second chapter of Design for Valor does get a recap -- Argosy always invited browsers to "start now" with Part Two -- but this by-the-numbers wartime stuff had little to offer. "Mr. Emerson Please Copy" is an odd piece of Americana with obvious slick ambitions from Frank Bunce, purporting to tell the story behind Ralph Waldo Emerson's aphorism about consistency being the hobgoblin of small minds by inventing a name-dropping correspondent for the philosopher who goes west with plans for a utopian community but acquires more practical pioneer values. There's nothing really wrong with the story except that it hardly seems like the stuff of pulp, which was often the problem with Argosy at this time. Finally, the larger size allows Argosy to offer short-short stories complete on one page, just like Collier's, and this issue's short-short, Ken Crossen's "The Bowmen of Mons," reads like wartime propaganda before we got into the war. It's a heroic French resistance story with German occupiers under attack by the legendary title figure, whose real identity is supposed to surprise us. World War II hurt the pulps, I feel, because an all-encompassing Manichean struggle of that sort limits the options of pulp heroes who are more properly freebooters or freelancers. But the war was only one of Argosy's problems, and none of them were going to be solved with this makeover.

If anyone wants to judge this issue for himself or herself, here's a link to a digital scan you can download for use on your favorite reading device:

THE PULP CALENDAR: January 25

I don't want to waste a Calendar entry on a 1941 Argosy -- instead, I'm going to give that thing a post of its own -- so here's a 1939 Short Stories featuring one of that pulp's most popular characters. L. Patrick Greene's Aubrey St. John Major -- the middle name is pronounced "Syngen" but he's usually called "The Major" -- actually began life in Adventure in 1919 before moving to Short Stories in 1921, while Greene continued to write other stories for Adventure. Pulp publishers didn't claim to own characters on any consistent basis, apart from those who had books named after them, so authors could move characters where he could get better a deal for them. Tarzan, for instance, bounced back and forth between Argosy and Blue Book depending on which would pay Edgar Rice Burroughs better. As for The Major, he was sort of a good-bad man in Africa, usually wanted for illegal diamond buying but often pitting himself against far worse characters. His sidekick was Jim the Hottentot, who called Major his baas and was prone to stock-African phrases like "wowee!" but evolved over time into a pretty heroic character in his own right. Elsewhere in this issue, Gordon Young's Red Clark also got his start in Adventure, but all but two of his serial adventures appeared in Short Stories, while Gene Van's Red Harris was a Short Stories man all the way from 1937 through 1944. Arthur O. Friel is identified with Adventure, and published his last story for that pulp this very month, but would wrap up his pulp career with ten more pieces for Short Stories over the next two years. As for the other cover-billed writers, Richard Howells Watkins spread himself out evenly across all the "big four" adventure pulps -- he's competent but nothing special -- while I'm not sure what Bruce Douglas did to earn his spot on top, since his piece for this issue was his first pulp story -- under this name, at least, in more than two years. A novella by prolific western write Harry Sinclar Drago and a short story by H.S.M. Kemp round out this 176 page issue. Since Short Stories published on the 10th and 25th during its long twice-monthly period, and no one else, I believe, appeared regularly on the 25th, this is the day of each month when you'll most likely see a cover from this popular pulp.

Sunday, January 24, 2016

PULP READING: Bill Gulick, "THE MADNESS OF BIG OLAF," DIME WESTERN, MAY 1948

Here's another scan from my copy of the May 1948 Dime Western. Bill Gulick was one of the last surviving western pulp writers -- I suspect the precocious John Jakes will be the last if he isn't already -- living 97 years to 2013. Several of his novels were made into movies, most notably Bend of the Snake, which became Anthony Mann's Bend of the River. May 1948 sees Gulick at the brink of a hiatus; he would not publish another pulp story for more than a year; he may have been working on Bend of the Snake at the time. "The Madness of Big Olaf" would be a textbook example of pulp's political incorrectness if anyone really cared how Swedes were portrayed in popular fiction. Gulick's title character is as much a stereotype as any ethnic character you might encounter. "You know Swedes," a character says, "And you know how they get after a winter in the woods. Like wildmen." The titular Swede's madness if only one of the protagonist's problems. The other is that he has to lay a certain amount of railroad track by a certain time to fulfill a contract -- a typical pulp situation -- but a business rival is running a saloon nearby to keep the hero's work crew, including numerous Swedish wild men, good and drunk. Big Olaf is mad at our hero because the hero knocked him out with a lucky punch in their first encounter. The hero figures out a way to solve both problems at once. I'm not really bothered by the stereotyping, but then again I'm no Swede. The story is neat and concise and as the first piece from Gulick that I've read it made a good impression. Click on the link below to read and judge for yourselves.

P.S.This story is sponsored, as you'll see, by the Mutual Radio Network. I find it interesting that the list of mystery programs in their ad doesn't feature their best-known show, The Shadow. Could that have something to do with him being a creature of a rival pulp publisher? He knows, probably.

Dime Western, May 1948

P.S.This story is sponsored, as you'll see, by the Mutual Radio Network. I find it interesting that the list of mystery programs in their ad doesn't feature their best-known show, The Shadow. Could that have something to do with him being a creature of a rival pulp publisher? He knows, probably.

THE PULP CALENDAR: January 24

This is the first time I want to criticize a cover artist. It seems like Paul Stahr should sell the drop and the peril facing the overdressed fellow trying to cross that body of water hand-over-hand by pulling back, but he goes for the relative close-up instead. Meanwhile, I don't know what the logger on the riverbank is staring and making a fist at, but it doesn't seem to be our hero. The story's probably better than the cover because it's by Frank Richardson Pierce, who I've found to be a dependable author, albeit best in the sardonic humor mode of the No-Shirt McGee stories. Apart from his opening chapter of a five-part serial the biggest attraction of this 1931 issue for me would be the novella by Theodore Roscoe, "Nightmare Island." Roscoe could get pretentious later on, at the end of the Thirties, in his American gothic Five Corners stories and his speculative history tales, but when he got good and pulpy, as in his zombie serials and Thibaut Corday's tall tales, he's very good indeed. This issue has four serials running, the others being Ralph Milne Farley's fantastic Caves of Ocean, George F. Worts's Gillian Hazeltine courtroom drama The Diamond Bullet, and Fred MacIsaac's Balata, which was recently reprinted by Altus Press as part of their Argosy Library collection. Pierce gets to profile himself in the occasional "Men Who Make the Argosy" page, and short stories by Harold dePolo, Alan K. Echols and Lt. John Hopper round out the issue. I'm not well-read enough yet to judge how good a lineup this is, but it looks promising.

Saturday, January 23, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: January 23

Argosy rarely limited itself to promoting only one story and one author on its covers, so the lack of verbiage on this 1932 cover should let you know that A. Merritt's Dwellers in the Mirage was an event. Merritt was a hugely popular but relatively unprolific author who had been identified with the Munsey company since his first stories began appearing in the publisher's All-Story Weekly in 1918. Dwellers was only his sixth serial to appear in Argosy since 1920. He'd pick up the pace by publishing another serial that fall. Another would come two years later, and that was it. Readers didn't like to wait for Merritt stories; he was one of the most requested authors among "Argonotes" letter writers. The rest of this issue's lineup isn't chopped liver. Erle Stanley Gardner contributes a novella featuring his western detective series character Whispering Story, while George F. Worts continues a serial featuring his Perry Mason precursor, defense attorney Gillian Hazeltine, and Fred MacIsaac wraps up The Golden Serpent. One of my favorites, Ralph R. Perry, has a short story, "The Dynamiter." If it's on the level of his Bellow Bill Williams stuff it'd be a treat. Robert A. Graef painted the risque cover, a reminder that pulps at their peak were contemporary with the Pre-Code period in movies and shared some of their transgressiveness. My own Argosy collection doesn't go quite this far back, but I'd say the venerable weekly was already in its peak period at this point.

Friday, January 22, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: January 22

If the cover story of this 1938 issue of Detective Fiction Weekly is "I Sell Strikes," I expect something about some sort of labor racketeer, not the montage of music notes, chorus girls, a grumpy old man and a giant martini glass the cover artist throws at us. Still, I've read enough of Richard Wormser, particularly his Dave McNally stories for Argosy, to trust him in whatever direction he takes the story. Two popular series continue in this issue as D. B. McCandless contributes another adventure of his female detective Sarah Watson and Judson P. Philips continues a Park Avenue Hunt Club serial. Steve Fisher, best known for I Wake Up Screaming, brings back his own series character, Tony Key, for the provocatively titled "Me and Mickey Mouse." Four short stories round out this issue's contents. Wormser and Fisher probably make this one worth a look if you don't mind being stuck in the middle of the serial

Thursday, January 21, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: January 21

There's a stark quality, almost abstract by pulp standards, to this 1939 Wild West Weekly cover by Harold Winfield Scott. This sort of close-up, with no faces visible, seems atypical of pulp cover art. As I've said already, there's a high standard of design to Street & Smith covers from this period, but I do wonder how well this one sold the issue to its target audience. Along with series hero the Silver Kid, who gets the cover story, this week's issue features one continuing character, Pete Rice, who used to have his very own magazine back when Street & Smith thought they could do hero pulps in all different genres. It also includes the last appearance of a short-lived series character, Guy L. Maynard's Far-Away Logan, who starred in six stories in as many weeks between December 17, 1938 and this issue. Maynard had greater success in Wild West Weekly with his Senor Red Mask. In addition to these prose personalities, there's a continuing comic strip character, Warren Elliot Carleton's Dusty Radburn, in the middle of a run that lasted from November 1938 to March 1939. Most of the authors in this issue are unfamiliar to me, so I can't really say more other than to admire that cover again.

Wednesday, January 20, 2016

PULP READING: Tom W. Blackburn, "Bring 'Em In Kicking!" DIME WESTERN, MAY 1948

Here's another story scanned from the pages of Popular Publications' May 1948 issue of Dime Western. Tom W. Blackburn was a busy pulpster of the period. In May 1948 he placed stories in seven different pulps, all but one for Popular. Four of those were novellas or novelettes, but "Bring 'Em In Kicking!" is a seven-page short story, refreshingly free of melodrama, by-the-numbers romance angles or the "yuhs" and "tuhs." It's basically a survival story as the hero has to bring an injured, uncooperative survivor of a raid back to the fort. Blackburn started out as a ghostwriter for some of the reputedly more prolific authors before publishing under his own name. By 1950 he had broken into the slicks, but his biggest success was to come in Hollywood, and not in prose. By far, Blackburn's most famous piece of writing is "The Ballad of Davy Crockett," the theme song for the epochal Disney TV series that he also scripted. Our story is just a little bit more edgy than that and is typical solid pulp writing from Blackburn. Click on the link below to download it and judge for yourself.

Dime Western, May 1948

THE PULP CALENDAR: January 20

Adventure adopted a thrice-monthly schedule in the fall of 1921 and stuck to it until the spring of 1926. That period is probably the high point of the magazine's long run. Editor Arthur Sullivant Hoffman somehow managed to maintain a high standard of quality throughout the period, cranking out 192 pages at a time. You'll notice that, compared to a successor in 1931 whose handiwork we saw a few days ago, Hoffman kept his covers understated. He doesn't promote an individual story but simply identifies his authors who, after all, are the stars of the magazine. Two in this 1924 issue really stand out. Arthur O. Friel specialized in adventures set in South America, ranging from the whimsical to the epic. He may be the most completely forgotten of Adventure's elite writers, if only because he left no real heirs in his geographic subgenre. But the long stories and bits of serials of his I've read from this period are often spectacular. Better still in this lineup, however, is Arthur D. Howden-Smith. This issue has one of his tales of Swain the Viking, an arrogant, no-nonsense personality who takes crap from no one, be it his jarl or his wife. Howden-Smith really tapped into something archaic yet accessible in Swain, a figure who would be a monster if he lived today but could be a hero on his own terms. I've enjoyed every story in the series that I've had a chance to read. Frontier story specialist Hugh Pendexter is the other big name in this number, which finds him in the middle of of The Long Knives, a five-part serial. An optimum issue of Adventure would have something from Harold Lamb, Talbot Mundy or Georges Surdez as well, but Friel and Howden-Smith on their own would make this particular issue worth having.

Tuesday, January 19, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: January 19

This 1935 issue of Detective Fiction Weekly begins the life work, at least in the pulp field, of Eugene Thomas. Of 26 stories reported in the Fiction Mags Index, all but one concern the cigarette-smoking sinister woman on the cover. All but one of those were written in a roughly two-year period, the series extending to the fall of 1936 before Thomas retired Vivian Legrand, only to revive her once in 1938. Legrand would seem to have led a hellacious life to provide Thomas with so much copy -- except that, like many a "true" story told in men's magazines for decades to come, this one was largely if not entirely made up. "The Lady From Hell" was a female supercriminal who, if she doesn't always win, always survives to fight another day. DFW didn't play by the "crime does not play" rules that comic books would adopt a short time later. The Lady shares space this issue with three recurring series characters: Anthony Rud's Jigger Masters, a debunking detective who dealt with pseudo-supernatural menaces; H. H. Matteson's Hoh-Hoh Stevens; and Edward Parrish Ware's Ranger Jack Calhoun. You also get your weekly cipher puzzle, a ju-jitsu instruction column by John Yamado, several more stories and another chapter of Fred MacIsaac's Man with the Club Foot. The Lady's debut and her GG cover art (by Lejaren Hiller) may make this a pricey issue, but probably not extremely so. That cover definitely does its job: I wouldn't mind learning the story behind it.

Monday, January 18, 2016

VINTAGE PAPERBACK OF THE WEEK: Fred Grove, COMANCHE CAPTIVES (1962)

My copy of Fred Grove's Spur award-winning novel is the third paperback printing from 1964, so the cover copy can crow about all the awards Grove won for the book. Grove studied writing under two pulpsters in college, Stanley Vestal and William Foster-Harris, but was a latecomer to fiction. His first published story appeared in the December 1951 Popular Western (Thrilling), and he has only twenty pulp credits total through 1957, according to the Fiction Mags Index. In a postscript to this edition, the publisher notes that Grove has "some Osage blood on the maternal side of his family," though for a long while it looks like this won't influence his novel's view of Indians.

For your information, the title refers to Comanches who are captives of the U.S. government, not whites who are captives of the Comanches. Our protagonist, Lt. Baldwin, is tasked with transporting the band of old chief Hard Shirt to a reservation with a skeleton crew of "defective" cavalry and a young Quaker schoolmarm. Rachel Pettijohn is an idealist whose compassionate solicitude for the Comanches clashes with Baldwin's bitter realism. His fiancee died (of a broken neck) when Indians attacked the stagecoach transporting her west and caused it to wreck. He is a realist rather than an outright bigot because he recognizes that injustices have been done to the Indians, yet believes that they are irreconcilable enemies of white civilization. They are motivated by hatreds that, however understandable, mean they cannot be trusted. Baldwin warns Rachel constantly that the Comanches will try to kill her whenever they get a chance, no matter how she tries to help them, because they can only see her as a white enemy. Here's a typical Baldwin argument:

"I don't know how many times I've warned you to stay away from the Indians," he said, reproving but not roaring, "You pay no attention. You go right back and run into trouble. You've got to remember certain things about Indians. They're wild, superstitious. Closer to nature than we are. They don't see life as we do." He was letting his thoughts run, impressing them. "How can you expect them to love white people when we are their bitterest enemies?"

Or later, shooting down another of Rachel's moments of optimism: "I was wrong. You don't know Comanches -- not yet. Any Indian will fawn over you if it fills his belly. Then cut out your heart the next day." Despite all this, you should not be surprised to learn that Baldwin and Rachel fall in love. Let's face it; that's why there's a woman in the story. It may be slightly less surprising to learn that Rachel turns out to be more right about the possibility of reconciliation than Baldwin had been willing to admit. While the narration early seems to reflect Baldwin's view of the Comanches -- Hard Shirt appears like anything but an honorable, dignified warrior -- a common ordeal eventually bonds the white protagonists with the Comanches as all end up besieged by a mob of Tejanos bent on lynching Hard Shirt and the other "bucks" among the captives. Like many such novels, Comanche Captives gives us a spectrum of characters illustrating white men's almost limitless capacity for depravity. Besides those late-arriving Tejanos. Baldwin has three enemies in his own unit: Van Horn, a disgruntled former fellow officer broken to the ranks for drinking; Stecker, a brutal bully with eyes on Rachel; and Ives, a cunning malcontent. If there's a subtext to the novel, it may be that while the Comanches' hatred and viciousness have obvious, readily recognized roots, whites seem capable of equal or greater viciousness for less obvious, less intelligible reasons. If the Comanches are Stone Age savages to Baldwin, his white antagonists appear downright evil.

The three antagonists don't quite live up to their potential. Van Horn disappears from the novel without getting any comeuppance after betraying Baldwin to the Tejanos. Grove seems to be setting Stecker up for an attempted rape of Rachel, but he and Ives are eliminated abruptly after a rash attempt to frag Baldwin. Comanche Captives proves episodic in construction; I could have believed it started existence as a serial, but Grove never did one of those in the pulps. The attack of the Tejanos comes out of nowhere -- except that it's spoiled in the teaser on the first inside page -- and serves mainly to set up the almost too-good-to-be-true finale in which Hard Shirt's people finally (and fully, presumably) embrace Rachel and Baldwin as friends, changing their name for the latter from Stone Heart to Stands Brave. Rachel and Baldwin embrace each other as well, and while the romance plot is by-the-numbers stuff, Comanche Captives is worthwhile for its action scenes and its overall refusal to idealize or demonize the Indians. At 140 pages, it's efficiently satisfying in a way that no longer seems profitable for the publishing industry, but writers (and editors) today could learn lessons from authors like Grove.

THE PULP CALENDAR: January 18

Here's the big change promised for Argosy in the venerable weekly's January 4 issue. If anything, the photo collage of actualities and movie images -- you can see Gary Cooper as Beau Geste at the bottom of the page, a mounted Zorro to his left, and Errol Flynn from either Captain Blood or The Sea Hawk at approximately 2 o'clock -- has made the standard cover format uglier than before. Argosy has become a "bedsheet," closer to the size of a standard magazine. It has reduced the page count again from 112 to 50 pages, but with three-column pages of smaller type than ever, it can claim to have more words than before. To give an idea of how well all this was received, less than two months later Argosy added 16 more pages to remedy readers' eye strain. Another drastic change in cover format would come in April. Every tweak since 1940 should have been an alarm bell; the once-mighty pulp was in big trouble.

I know no more about this issue than what's shown on the cover; the Fiction Mags Index has never seen the inside table of contents. All I can add is that a Bennett Foster western serial, Thunder Hoofs, continues this week while Louis C. Goldsmith's Fools Fly High concludes. Argosy plays one of its trumps this week; the weekly had introduced American audiences to C.S. Forester's Horatio Hornblower, in stories reprinted from British editions, back in 1938, and took credit for popularizing the British naval hero from the Age of Napoleon. Richard Sale was a familiar name for Argosy regulars, while Cleve L. Adams was a hard-boiled writer who was appearing regularly in Black Mask, Dime Detective and Detective Fiction Weekly at this time. The January 25 issue exists online in scanned form so I'll be taking a closer look at the transformed Argosy a week from now.

Sunday, January 17, 2016

From My Collection: DIME WESTERN, MAY 1948

My pulp collection consists of two types of magazines: general-interest adventure pulps like Argosy and Adventure, and westerns. You won't see my westerns on the Pulp Calendar because they're all monthlies. I don't own any of Street & Smith's weeklies or early biweekly issues of Dime Western. If I had any copies of Ranch Romances, the longest-surviving biweekly pulp, they'd be no good for the Calendar because they were dated as "First January Number" and so on. So my own westerns will appear on the blog as special attractions, including the added attraction of scanned stories and, depending on my ambitions, complete scanned issues down the line.

My pulp western collection ranges chronologically from 1948 -- this issue of Dime is my earliest -- to 1953, near the end of the pulp era. My thinking has been that pulp westerns should get better as time marches on, and that pulps from this particular period should share some of the virtues of the more mature movie westerns that were appearing in the same time period. Perhaps inevitably, the majority of my westerns are from Popular Publications. I have a few from the Thrilling Group, a couple from Stadium (some of the same people who gave us Marvel Comics) and so far only one title from Fiction House, and I probably should include two digest issues of Zane Grey's Western Magazine from Dell as well. Popular appears to have had the best westerns in this period, with less kiddie-like fare than Thrilling's more hero-oriented pulps. Many of the best authors appeared in pulps from all publishers, excepting probably bargain-basement Columbia, which ended up the only game in town at the bitter end of the era at the end of the Fifties.

Dime Western was the flagship of Popular's western line, though by 1948 the price belied the title. At this time Dime was smaller than Popular's other western monthlies at 98 pages, but the typeface was also smaller than the others', at least as far as I can tell from my contemporary copies of Star Western and scans of other Populars. You could feel like you were getting your money's worth despite the smaller page-count, and even at 15 cents Dime was still a dime cheaper than the other monthlies. This issue, at least, had some respectable advertising on the back cover. I like the audience targeting here; pulp readers are presumed to want to be writers someday.

The May 1948 issue has a respectable lineup. T. T. Flynn, author of the lead "novel" -- all 23 pages of it -- is the author of The Man From Laramie, from which the classic Anthony Mann-Jimmy Stewart film was made. Thomas Thompson is another major writer from this period, one who moved into TV writing post-pulp, mainly for Bonanza, for which he served for a time as a consultant. Marvin de Vries, Bill Gulick and Tom W. Blackburn were all dependable writers, while Bart Cassidy had been doing the comedy series about Tensleep Maxon since 1933. It was such a popular feature that issues used to have "A Tensleep Story" printed on their spines. I don't care for western comedy much, but to each his own. You'll see more of these people later, some of them in the week to come as I scan more stories. For now, your first taste of this issue will be George C. Appell's short story "Parson of Damnation." It's a harsh little tale of a man of God who proves to be not so much a man of peace as one might assume. I've liked just about everything I've read from Appell so far and I hope "Parson" at least amuses you. You can download it using the line below. Over the next week I plan to upload some more stories from this issue so be sure to come back for more.

Dime Western, May 1948

THE PULP CALENDAR: January 17

A perfunctory post this time since I have another longer post coming today. This is a 1931 Detective Fiction Weekly with a rare photo-cover with a "ripped from the headlines" type of framing effect. The nine-part memoir "I've Stolen $1,000,000!" is Henry Hyatt's only contribution to pulp literature, but he reputedly had a larger influence on pulp fiction. Hyatt claimed to be the inspiration for the archetypal safecracker Jimmy Valentine of O. Henry's famous story "A Retrieved Reformation." That story was adapted into a hugely popular, influential and oft-filmed play Alias Jimmy Valentine. Hyatt knew O. Henry when he and William Sidney Porter were fellow convicts, Porter supposedly pumping him for information that later went into the Valentine story. Interesting, DFW doesn't play up the Jimmy Valentine connection, on the cover at least, but when Hyatt's widow published the memoir as a book in 1949, after his death, she titled it Alias Jimmy Valentine Himself, By Himself. You can take a look at it at the Hathitrust Digital Library, a trove of old books scanned from college libraries and other sources.

Okay, that's already too much research for a perfunctory post, but I couldn't help myself. As for the actual detective fiction, this issue features three series characters: Erle Stanley Gardner's Sidney Zoom, J. Allen Dunn's Jimmy Dugan and Roland Philipps's Porky Neale. Fred MacIsaac has a serial running while Garnett Radcliffe and Harold DePolo contribute short stories. This issue presumably will appeal most to Gardner completists and those interested in the true-crime roots of popular fiction.

Okay, that's already too much research for a perfunctory post, but I couldn't help myself. As for the actual detective fiction, this issue features three series characters: Erle Stanley Gardner's Sidney Zoom, J. Allen Dunn's Jimmy Dugan and Roland Philipps's Porky Neale. Fred MacIsaac has a serial running while Garnett Radcliffe and Harold DePolo contribute short stories. This issue presumably will appeal most to Gardner completists and those interested in the true-crime roots of popular fiction.

Saturday, January 16, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: January 16

Here's a dramatic cover from 1937 fronting an issue of Detective Fiction Weekly with a decent array of talent. Lead author Fred MacIsaac was better known at this point for his "Rambler" series in Dime Detective. I've already described Judson Philips and D.B. McCandless, the latter of whom has another of his Sarah Watson stories in this issue. Paul Ernst tries to launch a new character, Bill Risk, this week, but Risk gets only one further outing according to the Fiction Mags Index. Also of interest inside is a non-fiction piece by "Convict 12627." Under this pseudonym Robert Arnold, later the author of a dictionary of underworld slang, had been writing stories of prison life since 1931, initially in Clayton Publications' Clues and later mostly for DFW. Respected detective writers Norman A. Daniels and Oscar Schisgall round out this week's offering. It isn't my ideal DFW lineup but for lots of people it'd do.

Friday, January 15, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: January 15

Adventure may be the greatest pulp that ever was. Starting as a monthly in 1911, it soon went biweekly and went thrice-montly at its peak in the early-mid 1920s. Issues from that period, edited by Arthur Sullivant Hoffman, are awesome assemblies of master storytellers: Harold Lamb, Talbot Mundy, Arthur O. Friel, Arthur D. Howden-Smith, Leonard H. Nason, the young Georges Surdez and many others in dense 192 page packages. Adventure's "Camp-Fire" section was the best letter column in the pulps, though it often gave more space to authors arguing with each other -- especially during an epic 1925 debate over Talbot Mundy's treatment of Julius Caesar in his Tros of Samothrace stories -- and to Hoffman's own rants against gun control -- than it did to mere readers' opinions. Hoffman was gone by the time this 1931 issue was published, and while longterm fans feel Adventure declined directly after his departure I've found issues between 1927, when he left, and 1932, when the Depression forced the magazine to halve its size, to remain quite formidable. The cover story is one of Gordon MacCreagh's tales of Kingi Bwana, an American in Africa. Kingi (or just plain King) has a Mutt and Jeff pair of African sidekicks, the wizened (and wise) Kaffa and the mighty Masai Barroungo. You can see an echo of their byplay in the similar team of N'Geeso and Tembu George in Fiction House's Ki-Gor series in Jungle Stories. I've just read a later Kingi Bwana story from a 1934 Adventure and it kicked ass in a kind of hateful way that I may discuss sometime. The other big name this issue is the aforementioned Talbot Mundy, largely forgotten now but not so long ago still widely in print; I remember paperback collections hyping Tros as a precursor of Conan the Barbarian, though they read nothing like that. In this issue Mundy continues the serial King of the World, starring one of his most popular series characters, the American agent of the British Secret Service, James "Jimgrim" Grim. During this period the nonfiction star of Adventure was "General Nogales," i.e. Rafael de Nogales, a Mexican soldier-of-fortune who recounted his globetrotting adventures in the magazine until its takeover by Popular Publications in 1934. Fred T. Everett contributed this typically distinctive cover. Look for Adventures on the Calendar most often on the 1st, 15th, 20th and 30th of each month, and look for my own personal copies down the line. As of now I own seven issues, five from the 1928-32 period, and two from the 1940s when Adventure was a monthly. That collection will grow soon.

Thursday, January 14, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: January 14

It's rare to see this sort of close-up on a 1930s pulp cover, though they became more commonplace a decade later, particular in Adventure and the later larger-sized Argosy. William Foster-Harris, the author of the cover story, was billed without his first name, apparently on the assumption that his hyphenated last name counted for two already. A western specialist overall, he was known best to Argosy readers as the author of a comedy series about a Mr. Weeble, a milquetoast type who always ended up with the upper hand. This week Foster-Harris was overshadowed by Edgar Rice Burroughs, who contributes part two of The Synthetic Men of Mars. That serial inspired a writer to the "Argonotes" letter column later in 1939 to suggest that Burroughs belonged in a psychopathic ward. Overshadowing perhaps even Burroughs today is an author starting a serial without getting the cover. This was a sort of slight to Cornell Woolrich, soon to become a legend of literary noir. But The Eye of Doom is less a true serial than a series of stand-alone stories linked by a common object passing from person to person, in this case a stolen Indian jewel. Rounding out this issue are a Johnston McCulley serial chapter, a boxing novella by Eustace Cockrell, a short story by Charles Tenney Jackson, probably about his series character Mase McKay, a sea story by Captain [A. E.] Dingle, and a short story by the possibly pseudonymous Odgers T. Gurnee, of whom I know and have read nothing. Emmett Watson did the cover. Burroughs and Woolrich together probably drive up the price of this issue, but apart from Woolrich, for whom Eye of Doom is lesser stuff, it doesn't have the talent that would make me pay for it.

Tomorrow we'll take our first look at another of the big general-interest pulps, so stay tuned!

Wednesday, January 13, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: January 13

In the wintry spirit of The Hateful Eight and The Revenant, here's a snowy cover scene from 1940. Edward Stevenson came up with this white-on-white composition, which may or may not illustrate the cover story. Seth Ranger is only in this issue because Frank Richardson Pierce is. That's because Ranger was Pierce, who I know and like best as the author of the No-Shirt McGee stories in Argosy and Short Stories. An editor might accept two stories from one author for an issue, but it somehow never looked good to let one author have multiple bylines. That's why torrential authors like Frederick Faust and H. Bedford-Jones had so many pseudonyms, and it's why Pierce had Seth Ranger. For whatever reason, Ranger is credited with the five-part serial starting this issue, while Pierce uses his own name for a short story. You'd think you'd use your real name for the big stuff, but maybe Ranger had become the more bankable name, or maybe Pierce felt the short story was the better work. That's presuming he had a say in which name got either byline. Also inside are the then-ubiquitous Walt Coburn and up-and-comer Wayne D. Overholser, who still had a long career ahead of him. If Ranger's westerns are as entertaining as Pierce's sourdough stories, this issue and the whole serial are probably worth getting.

Tuesday, January 12, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: January 12

When I don't want to do an Argosy my choice comes down to the other three major weeklies except on certain days of the month -- the 10th, 15th, 20th and 25th -- when the biweeklies or (in the case of Adventure in the early 1920s) thrice-monthlies appeared. For the rest of the days I decide which weekly's cover I like best -- I realize I'm excluding at least one weekly romance pulp, but I don't expect much from those covers -- and whether I can find a properly reproducible image online. Today Detective Fiction Weekly gets the nod for this grimly charming 1935 cover. Max Brand's "Spy!" isn't a serial but a sequence of stories featuring one Anthony Hamilton that started in the previous week's issue. Brand wrote nine stories during the year before wrapping the series up with a serial that December. Billed above the title is Judson P. Philips, who may be better known to mystery fans of a later generation as Hugh Pentecost. Philips had a long-running series in DFW about the Park Avenue Hunt Club, but "Blood Money" features a small-time series character, Grant Simon, who appeared in only four stories between September 1934 and May 1935. Also in this issue is Murray Leinster, best known today as a sci-fi writer, whose "Village of Plenty Fella Hell" definitely sports this week's most interesting title. The one actual serial going on at this time is Fred MacIsaac's "The Man With the Club Foot," which started last week. That "Selected By The Crime Jury" logo started the previous December. DFW gave it up the following summer. I have no idea whether the logo meant that some independent entity had endorsed the magazine or that a Crime Jury selected the contents of each issue. If we're lucky some DFW specialist may deign to enlighten us.

Monday, January 11, 2016

THE PULP CALENDAR: January 11

The cover of this 1936 issue doesn't identify the guy with the gun, but the taxi cab in the background leads me to guess that the gentleman's name is Smooth Kyle. Borden Chase, later to pen such classic western screenplays as Red River, Winchester '73, Vera Cruz and The Far Country, introduced Smooth, a cabbie turned government agent, in the 1935 serial Midnight Taxi, one year after he'd broken into Argosy with stories based on his experience as a sandhog or tunnel digger. I haven't read Midnight Taxi or this one, but I've read three later Kyle serials: 1937's Blue, White and Perfect and 1940's The Sun Sets at Five and Crooked Caribbean Cross. They're all quite entertaining, thanks especially to the banter between Smooth and his girlfriend Gilda, a hard-boiled dame with mob connections and a ruthless streak. I could believe that these stories got the attention of Howard Hawks, who hired Chase for Red River. The big name on the cover, or the one more people may recognize, is Erle Stanley Gardner. The creator of Perry Mason, who never appeared in a pulp, was a veteran pulpster who contributed lesser characters like Whispering Story and Major Brane to Argosy. The Fiction Mags index doesn't identify this week's story, "Slated to Die," with any continuing character, but that admirable reference remains far from comprehensive. H. Bedford-Jones continues a serial commemorating the centennial of Texas independence, Karl Detzer continues one of his firefighting serials, and Frederick "Max Brand" Faust continues one under his Dennis Lawton alias. Frederick C. Painton, an author I like, contributes a short story, but "Punch Drunk" suggests a boxing story, which is something outside his air war (or "war-air," as they said back then) and espionage specialties, so I don't know how good it might be. I've only just started to acquire Argosy issues from 1936, and unz.org has only one issue from that year, but it looks like anyone who collects the entire Chase serial will get a lot of good stuff along with it.

Sunday, January 10, 2016

VINTAGE PAPERBACK OF THE WEEK: Terry Spain, TIME TO KILL (1953)

Around the middle of the 20th century Americans decided they preferred one long story in an economical form than multiple stories in a bigger package. Thus the paperback novel supplanted the pulp magazine. Pulp authors adapted as best they could. Some never mastered the novel format and fell by the wayside. Others had better luck in Hollywood writing for movies or TV. Some of the pulp publishers became paperback publishers. Popular Library, for instance, was part of the same Ned Pines publishing empire that ran the Thrilling group of pulps. Terry Spain's novel, for instance, first appeared, presumably in condensed or preliminary form, in an issue of Mobsters, a very short-lived pulp -- it lasted only three issues -- from a period when Thrilling was flailing about in search of new formulas and cover gimmicks to save its pulp line. "Terry Spain" himself was a makeover. As Ted Stratton, he'd been writing pulp stories since 1935, mostly in the detective and sports genres. To my knowledge, Time to Kill is the only thing he published as Terry Spain.

Time to Kill is Stratton's attempt to play Mickey Spillane. His hero, Mack Barry, is in the tough, horny, hysterically righteous mode of Mike Hammer. Barry is a veteran turned private detective who's clearly looking for a new war to fight. He finds it in the small New Jersey town where his old buddy Willy Pickle lives. He's been hired by a bereaved father whose daughter was driven to kill herself by a drug habit. Barry's job is to find out who's pushing drugs in the area. While the father may have exposure and public action as a goal, the disinterestedly indignant Barry is ready to kill whoever the "fat cat" is. He faces two major obstacles. Much of local law enforcement is in the pocket of local crime boss Dominic Parente, and every woman Barry meets wants to screw him, from Willy Pickle's fiancee Wanda -- for whom Willy, now in the flower business, is a "god," for whose sake she'll have sex with Mack to make him go away -- to the "nymph" wife of an ineffectual county prosecutor, to Dominic Parente's borderline psycho young wife who goes into homicidal rages if someone strikes her.

Mack Barry is an old horndog and just a little misogynistic, but I suppose you can't blame him too much when women like Biz Parente try to run him over in a parking lot. Still, it seems a little excessive for him to take Wanda over his knee and spank her, after slapping her a few times, for setting him up with Ruth the "nymph" in an apparent attempt to compromise his mission. But I better let Mack explain his position:

That's the trouble with a stubborn woman. To keep you on the leash, she'll promise anything. She'll lie and lie. She'll scheme and plot, and she'll laugh if she succeeds. Laugh secretly, that is. There was too much work ahead to loiter with a woman.

Barry belies his opinion by continuing to loiter with women, but his sex and sexism pale in comparison to his indignation over drugs. Mack Barry, if not Terry Spain or Ted Stratton, has a livid case of reefer madness. Marijuana is always a gateway drug in his world, leading inevitably to heroin and more often than not to death. The modern stereotype of the passive stoner didn't exist yet; in the 1950s marijuana users were giggling hair-trigger psychos. In the novel, the Parente mob has opened a nightclub, the Helldorado, where drug parties take place in private basement booths. This is where Time to Kill's primary entertainment value for the modern reader is to be found, and Spain's descriptions should be quoted in detail. Ruth Crews has taken Mack to the Helldorado. When she tells him, "Relax, man," he knows what she is. "The use of man -- that's tea-pad jargon," he notes.

"Don't get so excited, man. I'm just a joy popper." She meant an occasional user, not a hooker, who has the dope habit. "Let's feel the bottle. I got need for the colored water, man."

"Marijuana and alcohol mixed," I said bitterly, and wanted to go upstairs, find Tony Scales and squeeze the blood from his snaky body. "Can you buy H here?"

"I'll ring for some."

"Don't bother. Do all the cellarites smoke reefers?"

"Maybe they come to watch the sights." You haven't seen anything, man. Wait till the amateurs get started on the dance floor." Ruth waved a languid hand. "Let's walk on the ceiling. Take off our clothes and sport." All this in a dreamy voice.

"Reefers are habit forming," I lectured.

Ruth giggled. Giggling is another sign of indulgence. Don't be a square. Let the monkey ride your back, man." Her body shook with silly laughter. "I'm careful of the stuff. I'll never get hooked."

They all say that at first. Ruth needed marijuana like a lake needs more water -- she was a nymph. Marijuana has the insidious property of turning decent girls into pseudo-nymphs.

After Mack rescues Ruth from a pot-fueled rape, the plot moves on. The mystery plot is who, exactly, is the fat cat, and while the teaser copy on the first inside page kind of gives this away, the ultimate big bad, the one behind the fat cat, proves to be someone else. Spain stocks his pool with enough red herrings to keep readers guessing awhile, but the mystery plot almost becomes moot when Barry convinces the local sheriff, a potentially shifty character -- to order a raid on the Helldorado. When the sheriff explains that he can't do anything without an order from the aforementioned ineffectual county prosecutor, Mack reminds him that he can take command of law-enforcement during a state of emergency like a big fire, an A-bomb explosion or a labor riot.

The dope racket is a state of emergency, sheriff. If you saw the cellar of Helldorado, you wouldn't just sit there. Local people buy reefers in that cellar. I saw young girls there, headed for a living death. And Helldorado isn't the only spot where teenagers can buy reefers and heroin either. Pushers work everywhere. Pushers give the stuff to kids and hook them into a steady trade....The dope situation demands that you declare a state of emergency and take over. You must supersede Frank Crews [the prosecutor] and his crooked detective bureau. You've got to protect every home and every teenager in this county. If you wipe out this dope racket, and you can, sheriff, every decent citizen, every mother and father will pin stars on your chest that will last a lifetime, believe me.

The sheriff is understandably reluctant -- "It might make me a kind of Hitler, taking the government from the people," -- until his teenage daughter comes home late from a date. Mack can't help noticing that "the loose sweater failed to hide the swelling signs of womanhood," and she can't help flirting with "such a handsome detective."

She stood there, no longer just a cute kid. There was a wanton invitation in the blue eyes. She pulled my hand to the right, turning my shoulder in toward her, then as she twisted toward her father, one burgeoning breast rubbed against my bare elbow.

Mack modestly admits that "I'm not that attractive to young girls." Instead:

There was an explanation for what the girl had done. Right here in this bright room, with two adults watching, Margaret Ann was stoned. She had been smoking reefers. She had the telltale red-rimmed eyes and the tattling bodily languor, and if I had said suddenly, 'Let's run off and ride the monkey's back' or 'Let's swing on the moon,' or something equally stupid, she would have giggled uncontrollably. She was a mere kid in her own home, under the eyes of her father, and she was as full of sex as Ruth Crews. If you smoke a joint, hit the weed hard, take off on a binge, you have no more morality than a common toad, no matter how old you are or what your upbringing has been.

And one Mack grabs her pocketbook, empties it onto the floor and reveals two joints, the sheriff's ethical scruples go up in smoke.

If it's hard from our distance to imagine anyone actually feeling this outraged toward marijuana, it's more plausible to see pot as a scapegoat for deeper social and cultural changes that were undermining the culture veterans like Mack Barry (if not 51 year old Ted Stratton) assumed they were fighting for. Something like that has to be behind the hero's guilty hostility toward the story's hypersexualized women, who all seem to come on strong like women never did before. Was this simply because of the greater "frankness" possible in paperbacks, or was this frankness describing something authors and readers considered new? I'll have a better idea, I hope, the more of these I read.

* * *

I bought this book back in 2014 in one of the used bookstores that still exist in the downtown area where I work. There used to be a lot more of those places, and I kick myself now when I think of all the paperback originals I could have picked up twenty or thirty years ago while I was browsing through different sections of those stores. Back then I wanted old magazines like Life or the Saturday Evening Post, or history books or else, as I grew older and less innocent, I browsed through the stores' photography sections. But you can't blame yourself for not wanting then what you want now. I'm just glad that there are still places where I can pay only $1.50 for this admittedly worn but still readably intact book. Over the past two years or so, while I began my pulp collection, I've also built up my vintage paperback collection. Not all of these are paperback originals, but many have the aesthetic virtues of the format. I like Popular Library paperbacks from this period for the layout, the fonts, and the cover paintings. More effort is made to sell the book with graphics -- necessarily since Terry Spain was an unknown quantity to potential readers -- than you see today in text-dominated covers emphasizing pre-sold authors. There's something campy about the packaging, I suppose, just as the contents inside seem campy today, but there's also an effort to reach out and grab the casual browser that's mostly missing today. I hope to read and review at least one novel each week from my collection, though not necessarily in as astonished detail as Time to Kill required. Not every novel may have as direct a link to pulp as this one had, but since paperback novels were direct descendants of pulp fiction, and part of the same golden age of storytelling, I hope pulp fans and general readers will enjoy this sample of wild things to come.

THE PULP CALENDAR: January 10

This 1944 issue is the only issue of Short Stories in my pulp collection to date. There's no special reason for the relative neglect. I was impressed by the few issues available in the unz.org trove and I've read some others that have been scanned and made available online. Short Stories was one of the most successful general-interest pulps. It maintained a more-than-monthly schedule longer than any other pulp with the phenomenal exception of Ranch Romances, finally becoming a monthly in the spring of 1949. Through the 1930s and until World War II it had 176 pages per issue, except for a brief period in 1932 when it escalated to 224. When the war came it shrunk slightly to 160 pages. My issue is the one of the last at that size; the magazine retrenched to 144 pages with the February 10 issue. 144 pages twice a month was still a lot of pulp in those days. Its rivals -- Adventure, Argosy and Blue Book -- all were monthly at this time, and the latter two had gone bedsheet. Adventure ran as high as 160 pages for a little while during the war but shrunk back to 144, and that was once a month. The same company that put Short Stories out was also publishing Weird Tales at this time. I don't know if they were doing anything else, but those two were plenty.

Let's take a little look around this issue. Here's the back cover.

Readers often complained about how the front covers embarrassed them, but some of these back-cover ads might have been more embarrassing. I'm going to do a post shortly about advertising in the pulps that will show a decline over time in the quality of back-cover advertising that's either effect or cause of the decline of pulp magazines as a fiction-delivery medium. You used to get better than this on the back, but it still wasn't always this bad, and there were pretty skunky advertisers even in the more golden days of a decade earlier. But now let's inspect this issue's sturdy spine.

I don't know when Short Stories started boasting of being "A Man's Magazine," but I do know that a couple of years earlier Blue Book started emphasizing "Stories of Adventure For Men, By Men." This insistence, implicitly exclusive by gender and age, points toward the evolution of pulp fiction into "men's adventure" as the original pulp audience splits demographically, the kids presumably adopting comic books while the women who always read pulps -- they wrote to Argosy all the time -- faced a sort of No Girls Allowed sign. At this point, though, Short Stories doesn't have the more sleazy or salacious content that defined "men's adventure." It's standard pulp stuff, with an inevitable wartime spin.