A man faces a test of character and responsibility when another man's son is kidnapped by mistake, in place of his own son. Movie fans will recognize that as the story of Akira Kurosawa's modern-dress classic High and Low (1963). Crime fiction fans will recognize it as the story of the novel that inspired Kurosawa, Ed McBain's King's Ransom (1959). The core idea most likely had been done many times before in pulp fiction. One such time was in the pages of the May 1952 issue of New Western, one of Popular Publications' stable of western titles. Clifton Adams' "Fighting Man Wanted!" doesn't have the class element of the McBain and Kurosawa stories. Instead, the protagonist and the father of the kidnapped boy are peers, more or less. William Toggleson and Clay Barnett are deputy marshals in amicable competition to succeed a retiring old-timer. Both men are reasonably well qualified, but Toggleson, our protagonist, is handicapped by his appearance. Toggleson simply doesn't dress the part. He's "A far cry from the fire-eating lawmen like Earp and Masterson and Hickock. But then I'd look darn foolish wearing leather vests and tied-down .45s just to sit behind a desk. Barnett is the favorite for the post "because he wore a wide-brim hat and high-heel boots and had two .45s tied down on his legs. And maybe because he had two notches in his guns, representing two outlaws he had killed." To drive the point home, the illustration on pae one is of Barnett, not Toggleson. Our protagonist had been a town-tamer in his heyday, but he never was a killer and that, combined with his modest dress, makes him hard to idolize. When his and Barnett's boys play outlaw, Clay's kid boasts that he's "a fightin' U.S. marshal, like my father," while young Toggleson says, "Ah ... I'm nothin' much, I guess."

It's that boasting that gets Clay's boy kidnapped by an outlaw out of prison and out for vengeance on Toggleson. Because of the circumstances, Toggleson feels responsible and talks Barnett after going after the boy himself. But he questions his resolve almost instantly. "He found himself thinking: I'd be a fool to go up there and let him kill me. It's not my son." Adams adds, "Immediately he felt ashamed of the thought." Yet he thinks it again as he closes in on the outlaw, though the thought doesn't stop him. This being a pulp western short story, there's no doubting that Toggleson will save the boy, slay the outlaw and earn the marshal's badge, but Adams still makes a halfway decent story out of it by stressing that Toggleson is not some picked-on loser who has to redeem himself for anything, as in the typical "coward" scenario, but simply someone suffering through a middle-age crisis of self-doubt despite the esteem of his community. The story reads as less cliched than it could or almost should be, and that's the mark of Clifton Adams' quality as a writer. He was one of the authors who made the last decade or so of pulp westerns a golden age of the genre.

Adventures in a Golden Age of Storytelling by SAMUEL WILSON, Author of "Mondo 70," "The Think 3 Institute," etc.

Thursday, August 31, 2017

Wednesday, August 23, 2017

SINGAPORE SAMMY: 'You ain't hard. You ain't smart. You're just a sucker.'

George F. Worts pulls off a nice piece of misdirection in the fourth Singapore Sammy story, "The Pink Elephant." (Short Stories, October 25, 1930). At the same time, he raises the stakes in Sammy Shea's hunt for his reprobate father, since I believe it's established here for the first time that the will which left Sammy his grandfather's fortune, but was stolen by his dad, contains a clause bestowing the estate upon the father in the event of Sammy's death. So just as we get our first real look at Bill Shea, we learn that he has a motive to kill his son. Sammy has tracked him to Siam (the present-day Thailand), where our hero's sob story has earned him the sympathy of a local prince who's equipped him with a handsome entourage of elephants and hunters to find the elder Shea. Early on, Sammy finally tracks has the old man in his sights -- or at least he finds a man who matches the description he depends on, that of a bearded man in the robes of a Buddhist monk, since Sammy himself hasn't seen the guy since he was two years old. After a tense, almost glancing encounter, Sammy is distracted from the chase by his abrupt discovery of the title creature, whom he rescues from crocodiles in a mud pit. The baby pink elephant is a phoouk, a rare and virtually sacred creature in Siam, and on sight of him Sammy is distracted from his potentially parricidal quest by that streak of greed that Worts has already well established. This changes the whole direction of the story, as Sammy realizes that he can earn a literally princely sum by delivering the phoouk to the king. The discovery also changes his relationship to the local prince and his minions, who feel that the pink elephant, being found in their master's territory, is his to deliver to the king, for whatever reward. Sammy understands that his trip to the capital will be dangerous, and that his erstwhile host will likely prove his enemy.

Into this tense situation wanders Sir Lester, a stereotypical Englishman touring the country "lookin' for big cats." His warning that Sammy runs "rather a risk" taking the phoouk all the way to Bangkok makes our hero suspicious. "Sammy looked quickly in Sir Lester's eyes," Worts writes, "saw something there that he did not like." But what else is new? Why wouldn't Sir Lester be just as eager to nab the elephant as anyone else? So Sammy has someone new to worry about -- except that the Englishman is not so new. After inviting Sammy to sit in a blatant trap and then springing it, Sir Lester reveals himself as Bill Shea. For this one time we can buy that Sammy could be so easily fooled because he hasn't had a good look at his father for so long. Once Sammy identifies him, Bill greets him with, "Smart boy! All you needed to find it out was a moving picture and a full set of directions!" Luckily for our hero, the old man is content to taunt him and steal his elephant.

Worts uses the occasion to recap the Sammy series to date from Bill's second-hand point of view before the old man absconds with the phoouk. He's arranged to have Sammy freed some time later, well after Bill and the pink elephant are out of reach -- or so Bill assumes. He hasn't reckoned with the bond Sammy has formed with Bozo, the prince's mighty alcoholic elephant. In the story's silly finish, Sammy steals Bozo from the prince's estate, fuels him up with whisky, overtakes Bill's party and manages to sneak off with the pink elephant. Score one for Sammy Shea! Silly as it is, "Pink Elephant" is a strong entry in the series thanks to its spectacular introduction, four episodes in, of the main villain, who promises to give Sammy still more trouble in the future.

Into this tense situation wanders Sir Lester, a stereotypical Englishman touring the country "lookin' for big cats." His warning that Sammy runs "rather a risk" taking the phoouk all the way to Bangkok makes our hero suspicious. "Sammy looked quickly in Sir Lester's eyes," Worts writes, "saw something there that he did not like." But what else is new? Why wouldn't Sir Lester be just as eager to nab the elephant as anyone else? So Sammy has someone new to worry about -- except that the Englishman is not so new. After inviting Sammy to sit in a blatant trap and then springing it, Sir Lester reveals himself as Bill Shea. For this one time we can buy that Sammy could be so easily fooled because he hasn't had a good look at his father for so long. Once Sammy identifies him, Bill greets him with, "Smart boy! All you needed to find it out was a moving picture and a full set of directions!" Luckily for our hero, the old man is content to taunt him and steal his elephant.

They told me that you were one dangerous guy to cross. Hell, you ain't hard. You ain't smart. You're just a sucker. I was almost gettin' proud of you -- and then you have to up and pull this stunt. You sucker!...What did I tell you in that letter I sent you when you were in the Singapore Hospital? 'The hand is faster than the naked eye. A wise man knows the aim of a bottle!' I warned you. You're just dumb.

Worts uses the occasion to recap the Sammy series to date from Bill's second-hand point of view before the old man absconds with the phoouk. He's arranged to have Sammy freed some time later, well after Bill and the pink elephant are out of reach -- or so Bill assumes. He hasn't reckoned with the bond Sammy has formed with Bozo, the prince's mighty alcoholic elephant. In the story's silly finish, Sammy steals Bozo from the prince's estate, fuels him up with whisky, overtakes Bill's party and manages to sneak off with the pink elephant. Score one for Sammy Shea! Silly as it is, "Pink Elephant" is a strong entry in the series thanks to its spectacular introduction, four episodes in, of the main villain, who promises to give Sammy still more trouble in the future.

Monday, August 21, 2017

'You are the hardest man to get to agree with anybody I ever saw. You won't even agree with yourself.'

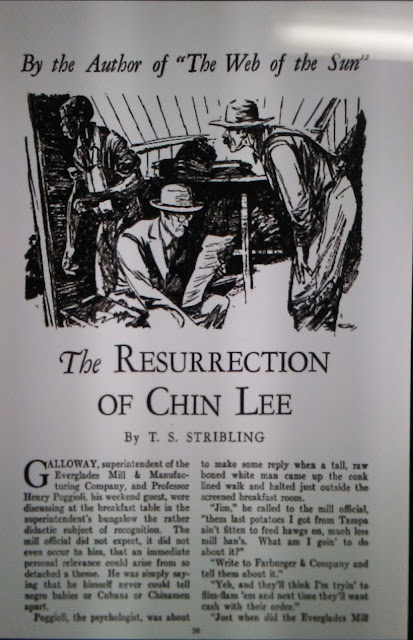

If you asked a pulp reader in the 1930s which writer for the story magazines had the best chance of entering the American literary canon, he might not say Dashiell Hammett, and he certainly wouldn't suggest H. P. Lovecraft. The reader might well nominate T. S. Stribling instead, because he had something, as of 1933, that neither Hammett, Lovecraft or probably anyone else writing for the pulps had even a chance of having: the Pulitzer Prize for the best American novel of the year. Stribling received that accolade for his 1932 novel The Store. In 1932 he also published three mystery stories in Adventure featuring his psychological detective, Dr. Henry Poggioli. If Stribling is remembered at all today, it's for the Poggioli series that became his meal ticket in later life, after publishers no longer accepted his novels. On the evidence of the few stories I've read, Poggioli combines Holmesian powers of observation with an inclination for sweeping generalizations along the lines of "only such and such a person would do this particular thing." With possibly a sense of irony, the conscious satirist Stribling addresses the subject of generalization in one of his 1932 Poggiolis, "The Resurrection of Chin Lee" (Adventure, April 15), which turns on a Florida mill owner's inability to tell Chinese people apart. Absurdly, Mr. Galloway makes this claim having known only one Chinese man in his whole life, his cook Chin Lee. "I see him only now and then, and I don't remember how he looks from one time to the next," Galloway explains.

"That really is odd," Poggioli replies, "I suppose it is a race obsession. You are so obsessed with Chin Lee's Chineseness, if I may coin a term, that your recognition stops there and doesn't reach the individual. It is probably based on our Anglo-Saxon superiority complex."

Cue the arrival of a perfectly stereotyped, dialect-speaking black security guard, who reports that he's just found Chin Lee murdered on the dock, with a bullet hole in his head. Desperate to clear himself, on the assumption that Galloway will accuse him of the murder, Sam has to admit that he didn't hear the gunshots because "take mo'n a pistol to wake me up when I'se night watchin'." Of course Poggioli will investigate, but when Sam brings him to the crime scene, Chin Lee's body is gone. The psychologist speculates that the body has been picked up and taken away with care, and not thrown to the sharks, because there's no trail of blood. From this he deduces that the killer is a woman. "She could not endure the thought of her lover's body being thrown to the sharks or given over to any stranger who found it, or to the callousness of a coroner's jury," he assumes. The killer must be a strong woman, capable of lifting and carrying a corpse Sam estimates at between 150 and 160 pounds.

One virtue of the Poggioli stories, however, is that Stribling is willing to let his detective follow a train of thought to a dead end. Poggioli's speculations become moot when Chin Lee is discovered alive in his shack, while the detective and his companions are searching for clues among the assumed victim's personal effects. Chin Lee claims to have knocked himself out trying to reel in a fish, only to come to and go home. Something isn't right, however, and with a little additional data Poggioli figures out what it is. As if fully aware of the inability of both Galloway and (apparently) Sam to tell Chinese men apart, a smuggling ring based in Cuba has been bringing in illegal immigrants one at a time, each taking a turn as Chin Lee until the next one comes to take his place. One of these Chin Lees actually was murdered, but to Poggiloi's possible disappointment the murderer isn't a woman. I won't spoil a mystery that people might read (this issue of Adventure has been scanned and uploaded to the internet), but I wonder whether it's worth it not to spoil this shaggy-dog tale. It's mildly amusing in a characteristically sardonic way -- as usual, Poggioli is surrounded by idiots -- but if Stribling had some point to make about prejudice or stereotyping, it's blunted by his own impulse to reduce characters like Sam to their dialects. As a matter of style, I get the impression that Stribling saw the Poggioli series, at this time at least, as self-conscious hackwork that paid the bills between novels. If you want to see him at full power, check out the available chapters of his 1923 serial Fombombo, an epic satire about a Babbitt in the middle of a South American revolution. For all I know, The Store might be worth a read as well, even if the actual canonical writers of Stribling's time looked down on Pulitzer winners -- until they got their own, that is.

"That really is odd," Poggioli replies, "I suppose it is a race obsession. You are so obsessed with Chin Lee's Chineseness, if I may coin a term, that your recognition stops there and doesn't reach the individual. It is probably based on our Anglo-Saxon superiority complex."

Cue the arrival of a perfectly stereotyped, dialect-speaking black security guard, who reports that he's just found Chin Lee murdered on the dock, with a bullet hole in his head. Desperate to clear himself, on the assumption that Galloway will accuse him of the murder, Sam has to admit that he didn't hear the gunshots because "take mo'n a pistol to wake me up when I'se night watchin'." Of course Poggioli will investigate, but when Sam brings him to the crime scene, Chin Lee's body is gone. The psychologist speculates that the body has been picked up and taken away with care, and not thrown to the sharks, because there's no trail of blood. From this he deduces that the killer is a woman. "She could not endure the thought of her lover's body being thrown to the sharks or given over to any stranger who found it, or to the callousness of a coroner's jury," he assumes. The killer must be a strong woman, capable of lifting and carrying a corpse Sam estimates at between 150 and 160 pounds.

One virtue of the Poggioli stories, however, is that Stribling is willing to let his detective follow a train of thought to a dead end. Poggioli's speculations become moot when Chin Lee is discovered alive in his shack, while the detective and his companions are searching for clues among the assumed victim's personal effects. Chin Lee claims to have knocked himself out trying to reel in a fish, only to come to and go home. Something isn't right, however, and with a little additional data Poggioli figures out what it is. As if fully aware of the inability of both Galloway and (apparently) Sam to tell Chinese men apart, a smuggling ring based in Cuba has been bringing in illegal immigrants one at a time, each taking a turn as Chin Lee until the next one comes to take his place. One of these Chin Lees actually was murdered, but to Poggiloi's possible disappointment the murderer isn't a woman. I won't spoil a mystery that people might read (this issue of Adventure has been scanned and uploaded to the internet), but I wonder whether it's worth it not to spoil this shaggy-dog tale. It's mildly amusing in a characteristically sardonic way -- as usual, Poggioli is surrounded by idiots -- but if Stribling had some point to make about prejudice or stereotyping, it's blunted by his own impulse to reduce characters like Sam to their dialects. As a matter of style, I get the impression that Stribling saw the Poggioli series, at this time at least, as self-conscious hackwork that paid the bills between novels. If you want to see him at full power, check out the available chapters of his 1923 serial Fombombo, an epic satire about a Babbitt in the middle of a South American revolution. For all I know, The Store might be worth a read as well, even if the actual canonical writers of Stribling's time looked down on Pulitzer winners -- until they got their own, that is.

Tuesday, August 15, 2017

'She either surrenders those papers or shall be stripped as naked as the day she was born!'

Beneath the magnolias and grits of Civil War fiction, Gordon Young's "The Loyal Lady" (The Big Magazine, 1935) is a properly paranoid spy story. In 1862 Captain Haynes of the Union army is sent south across enemy lines incognito to get accurate information on the size of General Lee's army. Lee's opposite number, Gen. McClellan, has been paralyzed, to Commander-in-Chief Lincoln's dismay, by apparently exaggerated reports of the Confederate force he faces. Haynes hopes to pump a Major Rawks for information, but finds Rawks hunting for a Union spy, a southern belle turned turncoat, who's just stolen just the papers Haynes is looking for. Rawks provokes Haynes' sense of chivalry, not to mention his patriotism, by vowing to hang the supposed spy, Maybelle Marshall, hanged, despite her safe-conduct pass from Jefferson Davis himself. Worse, when they actually meet Miss Marshall, Rawks insists on a full-body search.

A corporal is unwilling to do this grim work, and a backwoods private gets his face slapped for trying. Rawks decides to do the job himself, but Haynes -- still in disguise as a brother Rebel officer -- refuses to allow it. Rather than fight, Rawks agrees to leave the search to Dinah, his "buxom negress" maidservant, who reports back empty-handed. It turns out, however, that Dinah is, understandably, a clandestine Yankee sympathizer. "Black folks dey know dat de Yankees is a-fittin fo' us," she explains. She doesn't trust Haynes, unable to look past his southern uniform, but Marshall accepts his assistance in a daring escape. In return, her gift of a Derringer enables Haynes to escape after Rawks finally figures him out. In the end, Haynes learns that Rawks and Marshall had set him up. It had all been a play designed to get Haynes, whose coming they learned of from black spies within the household of Haynes' commanding officer, to deliver more fake intelligence back north. That bemused commander offers the story's moral: "When any Southern girl tells you she is loyal to her country -- don't be a fool! Believe her. She means the South!"

The Big Magazine was a one-shot published by Popular Publications in 1935, shortly after they acquired Adventure. The idea, historians say, was to burn off excess inventory for that prestigious pulp. If so, it was an odd decision considering that Popular had recently restored Adventure to a twice-a-month schedule, and that The Big Magazine's lineup was almost a Murderer's Row of pulp aces. Based on what I've read of it so far -- I'm not quite halfway through its 224 pages -- my hunch is that The Big was more of a dumping ground for subpar stuff from those top authors, some of it fairly old, to judge from the Prohibition setting of one story. "The Loyal Lady" is one of the better stories so far, nicely plotted if also marred by cringeworthy "negro" dialect. Any persistent pulp reader has got to get used to dialect dialogue; if you can't tolerate it you're reading the wrong stuff. To be fair, he also writes dialect for the backwoods soldiers, e.g. "Shore! An' we brunged her here." But there's a difference, or so I like to think, between dialect and comedy dialect. Dinah's dialogue marks her as a comedy relief character. It's embarrassing to read in a way the backwoods dialect isn't. "Oh, Lordy-lord!" she cries, warning Maybelle against first Haynes, then Rawks. "Don' yo' b'lief 'im, honey! A gemman he say anything fo' to fool a lady....Lordy-lord! We-all is sho' gwine git murdered by dat major-man!" Lordy-lord, indeed! Large historical claims are made for Gordon Young as, if not a pioneer, then a precursor of the hard-boiled style. From what I've read of him, that's more a matter of attitude, as might be seen here as well as in his more relevant Don Everhard stories, than of style. Young's style strikes me as stilted, but in the melodramatic setting of "The Loyal Lady" it feels almost correct. But it's the twist ending and the overall feeling that anyone could be a spy that give Young's story an almost-modern flavor.

"Barbarous, sir!" said Haynes desperately.

"Undoubtedly," the major agreed with composure, "But war, my friend. She is a traitor. And one who has no honor can not claim the protection of decency and modesty. Corporal, disrobe the woman!"

A corporal is unwilling to do this grim work, and a backwoods private gets his face slapped for trying. Rawks decides to do the job himself, but Haynes -- still in disguise as a brother Rebel officer -- refuses to allow it. Rather than fight, Rawks agrees to leave the search to Dinah, his "buxom negress" maidservant, who reports back empty-handed. It turns out, however, that Dinah is, understandably, a clandestine Yankee sympathizer. "Black folks dey know dat de Yankees is a-fittin fo' us," she explains. She doesn't trust Haynes, unable to look past his southern uniform, but Marshall accepts his assistance in a daring escape. In return, her gift of a Derringer enables Haynes to escape after Rawks finally figures him out. In the end, Haynes learns that Rawks and Marshall had set him up. It had all been a play designed to get Haynes, whose coming they learned of from black spies within the household of Haynes' commanding officer, to deliver more fake intelligence back north. That bemused commander offers the story's moral: "When any Southern girl tells you she is loyal to her country -- don't be a fool! Believe her. She means the South!"

The Big Magazine was a one-shot published by Popular Publications in 1935, shortly after they acquired Adventure. The idea, historians say, was to burn off excess inventory for that prestigious pulp. If so, it was an odd decision considering that Popular had recently restored Adventure to a twice-a-month schedule, and that The Big Magazine's lineup was almost a Murderer's Row of pulp aces. Based on what I've read of it so far -- I'm not quite halfway through its 224 pages -- my hunch is that The Big was more of a dumping ground for subpar stuff from those top authors, some of it fairly old, to judge from the Prohibition setting of one story. "The Loyal Lady" is one of the better stories so far, nicely plotted if also marred by cringeworthy "negro" dialect. Any persistent pulp reader has got to get used to dialect dialogue; if you can't tolerate it you're reading the wrong stuff. To be fair, he also writes dialect for the backwoods soldiers, e.g. "Shore! An' we brunged her here." But there's a difference, or so I like to think, between dialect and comedy dialect. Dinah's dialogue marks her as a comedy relief character. It's embarrassing to read in a way the backwoods dialect isn't. "Oh, Lordy-lord!" she cries, warning Maybelle against first Haynes, then Rawks. "Don' yo' b'lief 'im, honey! A gemman he say anything fo' to fool a lady....Lordy-lord! We-all is sho' gwine git murdered by dat major-man!" Lordy-lord, indeed! Large historical claims are made for Gordon Young as, if not a pioneer, then a precursor of the hard-boiled style. From what I've read of him, that's more a matter of attitude, as might be seen here as well as in his more relevant Don Everhard stories, than of style. Young's style strikes me as stilted, but in the melodramatic setting of "The Loyal Lady" it feels almost correct. But it's the twist ending and the overall feeling that anyone could be a spy that give Young's story an almost-modern flavor.

Wednesday, August 9, 2017

'He go hell, I no can catch!'

Imagine the stories Arthur O. Friel might write about Venezuela in the 21st century: the intrigues of Chavistas, dissidents and military men, Cubans and Americans, etc. Venezuela was Friel's meat. He explored the territory himself and wrote both fiction and non-fiction about it. Friel was one of the star writers for Adventure in the 1920s, but his output slowed over the course of the 1930s, and his work became less ambitious. In 1938 he created the character Dugan, whose exploits are reported by raconteurs addressing the reader in the second person, a favorite Friel device. As noted often here, because most pulp writers were freelancers, their characters were rarely considered the intellectual property of any one publisher. As a result, Dugan could wander back and forth between Adventure, where he first appeared, and Short Stories, where "Under Dog" appeared in the January 25, 1939 issue. The narrator has detailed knowledge of Dugan's exploits, though he doesn't take part in the story he tells. He claims to be a "side-kick" of Dugan, though I suppose he could be Dugan himself, whom he describes as "a husky lad about my size with big fists and no brains." In other words, a conventional tough-guy pulp hero who falls in with a suspicious band of traders after saving an accused thief they'd been shooting at. The lead trader is suspicious because he talks funny: "The words were English -- or North American -- with something a little queer in the long ones." He calls himself Brockley but pronounces it "Broccoli" ("Some kind of wop cabbage," the narrator explains). Brockley's unlikely mission is to bring a consignment of frying pans across the border from Venezuela to Colombia, Dugan has his doubts; the pans will most likely be melted down so the metal can be put to more militant use. He doesn't need the money Brockley offers him, but he hopes to shake "some people who didn't like him" who'd been following him north from some previous adventure. He'd be a minority of one if not for the loyalty of Tonio, the Indian he rescued.

As it turns out, Brockley has firearms very carefully packed within his load of frying pans, and he's set up Dugan to be the fall guy if the sale goes sour. And of course it does go sour, thanks to a German working for the Venezuelan government, who gives Friel the opportunity to write a more blatant accent than Brockley's. It's actually not as extremely vaudevillian as some writers got; the accent is mostly restricted to "ch" for "j" and the occasional hiss. He's about to have Dugan executed for gun-running when Tonio speaks up to exonerate him and explain his own beef with Brockley -- the man who killed his mother and left him to be raised in a squalid Indian village. The unimpressed German's going to shoot everybody anyway, but Dugan and Tonio fight their way out, while Brockley is killed in the crossfire, denying Tonio his revenge. "It's funny, the way wise guys go flop and dumb birds like me and Dugan keep drifting along," the narrator reflects. In fact, Dugan had at least two more stories in him, at least according to the FictionMags Index, one appearing the same month in Adventure. This particular short story is a far cry from the epic stuff Friel wrote in the Twenties, but even late in his career -- his last pulp stories appeared in 1941 -- he had enough juice to make his stuff readably entertaining.

As it turns out, Brockley has firearms very carefully packed within his load of frying pans, and he's set up Dugan to be the fall guy if the sale goes sour. And of course it does go sour, thanks to a German working for the Venezuelan government, who gives Friel the opportunity to write a more blatant accent than Brockley's. It's actually not as extremely vaudevillian as some writers got; the accent is mostly restricted to "ch" for "j" and the occasional hiss. He's about to have Dugan executed for gun-running when Tonio speaks up to exonerate him and explain his own beef with Brockley -- the man who killed his mother and left him to be raised in a squalid Indian village. The unimpressed German's going to shoot everybody anyway, but Dugan and Tonio fight their way out, while Brockley is killed in the crossfire, denying Tonio his revenge. "It's funny, the way wise guys go flop and dumb birds like me and Dugan keep drifting along," the narrator reflects. In fact, Dugan had at least two more stories in him, at least according to the FictionMags Index, one appearing the same month in Adventure. This particular short story is a far cry from the epic stuff Friel wrote in the Twenties, but even late in his career -- his last pulp stories appeared in 1941 -- he had enough juice to make his stuff readably entertaining.

Monday, August 7, 2017

SINGAPORE SAMMY vs 'the toughest egg south of Shanghai'

Still hunting his reprobate father, Singapore Sammy Shea is hunted himself in his third story, "South of Sulu." (Short Stories, June 25, 1930). Ever since word got out that he had brought in the infamous Blue Fire Pearl of Malobar to be appraised, the scum of sea of land have been gunning for him and the pearl. Following a lead on his father, Sammy encounters three such characters on the island of Pelambang. Peddy the trader, stereotypically fat, runs the place. Whisky Wallace is one of his henchman. Their uncomfortable partner is Big Nick Stark, "the toughest egg south of Shanghai," who feels that his cut of the loot to be taken from Sammy doesn't really reflect his contributions to the endeavor. Sammy's no fool and leaves his pearl in a secure location on his boat before setting foot on Peddy's island, where he is predictably ambushed by the terrible trio. They tie him up and threaten torture if he doesn't come across, but with each working at cross purposes against the others Sammy has an opening to escape. Things get pretty hard-boiled as the bad guys threaten to put a lit cigar, a broken bottle, etc. in Sammy's face, but this all proves to be prelude to Sammy's battle of wits with Big Nick. Detecting a double-cross from Peddy, and killing him off-stage, Stark offers to join forces with Sammy, luring the good-but-greedy Singapore with the long-sought mate to the Blue Fire Pearl. Sammy is greedy enough to gamble his pearl against Stark's, and once he agrees to that we remember the scene early in the story where Big Nick impressed Peddy with his fancy shuffling and dealing. Worts knows how to keep things suspenseful by having his bad guys often stay at least a step ahead of Sammy, and he increases readers' anxiety by having Sammy lose at cards to Nick not once, not twice, but thrice -- the last time with his life at stake, since losing obliges Sammy to swim through shark-infested water to get rescuers to their stranded boat.

Stark apparently has an uncanny yet deceptive shuffle that looks guilelessly awkward even to a practiced eye like Sammy's, yet infallibly delivers Big Nick the winning hand. It's a bit of a cheat that Worts never actually explains Nick's technique, but has Sammy finally find proof of his cheating by accident -- he'd left an ace in the box quite by mistake, yet Nick dealt himself four aces. Worts is also wise to give Nick plenty of time to make his spiel, as if trying to wear down the reader's resistance as Nick is trying to wear down Sammy's. And for the hell of it, the antagonists have to forget their differences long enough to get their boat through a nasty storm. It keeps you wondering whether Nick will prove a good egg after all, rather than a mere tough one. "South of Sulu" gives us a likably nasty Sammy instead of the self-righteous con man of the previous story, "Cobra." He gets great tough-guy dialogue, telling Nick that "If you put her aground, one second later your backbone's gonna think an elephant's takin' a walk on it," or that "for the pure pleasure of it, I could turn you into curry of lead." It's still not as good as the original entry, "The Blue Fire Pearl," but you're more likely to keep following Sammy on his quest after this one than after "Cobra." There are two more to go in the first Altus Press volume of Sammy stories, and then I'll jump ahead in time to some later items from my own collection. Stay tuned.

Stark apparently has an uncanny yet deceptive shuffle that looks guilelessly awkward even to a practiced eye like Sammy's, yet infallibly delivers Big Nick the winning hand. It's a bit of a cheat that Worts never actually explains Nick's technique, but has Sammy finally find proof of his cheating by accident -- he'd left an ace in the box quite by mistake, yet Nick dealt himself four aces. Worts is also wise to give Nick plenty of time to make his spiel, as if trying to wear down the reader's resistance as Nick is trying to wear down Sammy's. And for the hell of it, the antagonists have to forget their differences long enough to get their boat through a nasty storm. It keeps you wondering whether Nick will prove a good egg after all, rather than a mere tough one. "South of Sulu" gives us a likably nasty Sammy instead of the self-righteous con man of the previous story, "Cobra." He gets great tough-guy dialogue, telling Nick that "If you put her aground, one second later your backbone's gonna think an elephant's takin' a walk on it," or that "for the pure pleasure of it, I could turn you into curry of lead." It's still not as good as the original entry, "The Blue Fire Pearl," but you're more likely to keep following Sammy on his quest after this one than after "Cobra." There are two more to go in the first Altus Press volume of Sammy stories, and then I'll jump ahead in time to some later items from my own collection. Stay tuned.

Wednesday, August 2, 2017

'What this country needs is more Chinese.'

"That wouldn't be honest," he stated coldly.

"Why not?" argued Jim, heating up under censure, "He's sneaking a bunch of Chinks into the country, ain't he? Don't he deserve to be caught?"

Denny was like a rock. "Where's the harm in it?" he demanded. "What this country needs is more Chinese."

"Huh?"

"Well do I remember my old man saying, many's the time when he was out of work, 'Twinty two families in the house an' devil a Christian in the lot but wan Jew an' two Chinese.' We'd of starved, I'm tellin' you, if it weren't for a fat yellow grinnin' Chinese that owned a grocery around on Pell Street."

With more energy he added, "An' don't be callin' 'em Chinks. A Jap is a Jap but a Chink is a Chinese, an willin' to be white if ye give him half a chance."

There proves to be an easy solution to this impasse. Once Jim suggests that Ferrer, the Cuban, could be smuggling in a Japanese, Denny jumps to the conclusion that this theoretical person is a spy "comin' in under cover because we're tightening up on some of our bowin' and apologizin' to Jap visitors." The government will really pay out for reporting a spy, he concludes, while Jim argues for quantity over quality, assuming that the feds will pay more for a boatload of Chinese illegals. "Where's your patriotism, man?" Denny protests at this thought. "Up North," Jim answers.

Watkins cleverly avoids making clear whether or not the man our heroes eventually discover is Chinese or Japanese. Sure, the man cries out, "No Jap! Chinese!" before jumping ship, and sure, Denny boasts of his ability to tell Chinese and Japanese apart, but just because "the face was the face of a Chinese if Denny Coyle were any judge," that doesn't mean Denny's any judge. In any event, "the Oriental" turns out to be smuggling diamonds, leading Denny to observe, on his assumption that the "yellow man" was Chinese, that "the Chinese are a clever race -- sometimes too clever, belike!" Diamonds actually draw a pretty good reward that Jim and Denny share equally with Old Craikie, who has also talked of "going North" soon. The end of the story explains the title: Craikie dies moments after putting his share of the bills in his sock. To Denny that means "the old one's further North than you or me will ever get if we go to the pole." Modest as it is, "Two Ways North" may be the best thing I've read from Watkins to date.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)