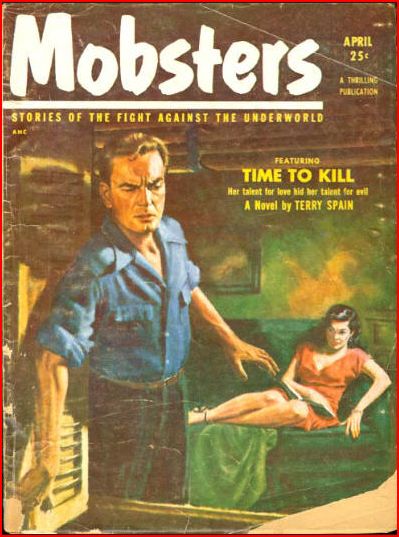

Around the middle of the 20th century Americans decided they preferred one long story in an economical form than multiple stories in a bigger package. Thus the paperback novel supplanted the pulp magazine. Pulp authors adapted as best they could. Some never mastered the novel format and fell by the wayside. Others had better luck in Hollywood writing for movies or TV. Some of the pulp publishers became paperback publishers. Popular Library, for instance, was part of the same Ned Pines publishing empire that ran the Thrilling group of pulps. Terry Spain's novel, for instance, first appeared, presumably in condensed or preliminary form, in an issue of Mobsters, a very short-lived pulp -- it lasted only three issues -- from a period when Thrilling was flailing about in search of new formulas and cover gimmicks to save its pulp line. "Terry Spain" himself was a makeover. As Ted Stratton, he'd been writing pulp stories since 1935, mostly in the detective and sports genres. To my knowledge, Time to Kill is the only thing he published as Terry Spain.

Time to Kill is Stratton's attempt to play Mickey Spillane. His hero, Mack Barry, is in the tough, horny, hysterically righteous mode of Mike Hammer. Barry is a veteran turned private detective who's clearly looking for a new war to fight. He finds it in the small New Jersey town where his old buddy Willy Pickle lives. He's been hired by a bereaved father whose daughter was driven to kill herself by a drug habit. Barry's job is to find out who's pushing drugs in the area. While the father may have exposure and public action as a goal, the disinterestedly indignant Barry is ready to kill whoever the "fat cat" is. He faces two major obstacles. Much of local law enforcement is in the pocket of local crime boss Dominic Parente, and every woman Barry meets wants to screw him, from Willy Pickle's fiancee Wanda -- for whom Willy, now in the flower business, is a "god," for whose sake she'll have sex with Mack to make him go away -- to the "nymph" wife of an ineffectual county prosecutor, to Dominic Parente's borderline psycho young wife who goes into homicidal rages if someone strikes her.

Mack Barry is an old horndog and just a little misogynistic, but I suppose you can't blame him too much when women like Biz Parente try to run him over in a parking lot. Still, it seems a little excessive for him to take Wanda over his knee and spank her, after slapping her a few times, for setting him up with Ruth the "nymph" in an apparent attempt to compromise his mission. But I better let Mack explain his position:

That's the trouble with a stubborn woman. To keep you on the leash, she'll promise anything. She'll lie and lie. She'll scheme and plot, and she'll laugh if she succeeds. Laugh secretly, that is. There was too much work ahead to loiter with a woman.

Barry belies his opinion by continuing to loiter with women, but his sex and sexism pale in comparison to his indignation over drugs. Mack Barry, if not Terry Spain or Ted Stratton, has a livid case of reefer madness. Marijuana is always a gateway drug in his world, leading inevitably to heroin and more often than not to death. The modern stereotype of the passive stoner didn't exist yet; in the 1950s marijuana users were giggling hair-trigger psychos. In the novel, the Parente mob has opened a nightclub, the Helldorado, where drug parties take place in private basement booths. This is where Time to Kill's primary entertainment value for the modern reader is to be found, and Spain's descriptions should be quoted in detail. Ruth Crews has taken Mack to the Helldorado. When she tells him, "Relax, man," he knows what she is. "The use of man -- that's tea-pad jargon," he notes.

"Don't get so excited, man. I'm just a joy popper." She meant an occasional user, not a hooker, who has the dope habit. "Let's feel the bottle. I got need for the colored water, man."

"Marijuana and alcohol mixed," I said bitterly, and wanted to go upstairs, find Tony Scales and squeeze the blood from his snaky body. "Can you buy H here?"

"I'll ring for some."

"Don't bother. Do all the cellarites smoke reefers?"

"Maybe they come to watch the sights." You haven't seen anything, man. Wait till the amateurs get started on the dance floor." Ruth waved a languid hand. "Let's walk on the ceiling. Take off our clothes and sport." All this in a dreamy voice.

"Reefers are habit forming," I lectured.

Ruth giggled. Giggling is another sign of indulgence. Don't be a square. Let the monkey ride your back, man." Her body shook with silly laughter. "I'm careful of the stuff. I'll never get hooked."

They all say that at first. Ruth needed marijuana like a lake needs more water -- she was a nymph. Marijuana has the insidious property of turning decent girls into pseudo-nymphs.

After Mack rescues Ruth from a pot-fueled rape, the plot moves on. The mystery plot is who, exactly, is the fat cat, and while the teaser copy on the first inside page kind of gives this away, the ultimate big bad, the one behind the fat cat, proves to be someone else. Spain stocks his pool with enough red herrings to keep readers guessing awhile, but the mystery plot almost becomes moot when Barry convinces the local sheriff, a potentially shifty character -- to order a raid on the Helldorado. When the sheriff explains that he can't do anything without an order from the aforementioned ineffectual county prosecutor, Mack reminds him that he can take command of law-enforcement during a state of emergency like a big fire, an A-bomb explosion or a labor riot.

The dope racket is a state of emergency, sheriff. If you saw the cellar of Helldorado, you wouldn't just sit there. Local people buy reefers in that cellar. I saw young girls there, headed for a living death. And Helldorado isn't the only spot where teenagers can buy reefers and heroin either. Pushers work everywhere. Pushers give the stuff to kids and hook them into a steady trade....The dope situation demands that you declare a state of emergency and take over. You must supersede Frank Crews [the prosecutor] and his crooked detective bureau. You've got to protect every home and every teenager in this county. If you wipe out this dope racket, and you can, sheriff, every decent citizen, every mother and father will pin stars on your chest that will last a lifetime, believe me.

The sheriff is understandably reluctant -- "It might make me a kind of Hitler, taking the government from the people," -- until his teenage daughter comes home late from a date. Mack can't help noticing that "the loose sweater failed to hide the swelling signs of womanhood," and she can't help flirting with "such a handsome detective."

She stood there, no longer just a cute kid. There was a wanton invitation in the blue eyes. She pulled my hand to the right, turning my shoulder in toward her, then as she twisted toward her father, one burgeoning breast rubbed against my bare elbow.

Mack modestly admits that "I'm not that attractive to young girls." Instead:

There was an explanation for what the girl had done. Right here in this bright room, with two adults watching, Margaret Ann was stoned. She had been smoking reefers. She had the telltale red-rimmed eyes and the tattling bodily languor, and if I had said suddenly, 'Let's run off and ride the monkey's back' or 'Let's swing on the moon,' or something equally stupid, she would have giggled uncontrollably. She was a mere kid in her own home, under the eyes of her father, and she was as full of sex as Ruth Crews. If you smoke a joint, hit the weed hard, take off on a binge, you have no more morality than a common toad, no matter how old you are or what your upbringing has been.

And one Mack grabs her pocketbook, empties it onto the floor and reveals two joints, the sheriff's ethical scruples go up in smoke.

If it's hard from our distance to imagine anyone actually feeling this outraged toward marijuana, it's more plausible to see pot as a scapegoat for deeper social and cultural changes that were undermining the culture veterans like Mack Barry (if not 51 year old Ted Stratton) assumed they were fighting for. Something like that has to be behind the hero's guilty hostility toward the story's hypersexualized women, who all seem to come on strong like women never did before. Was this simply because of the greater "frankness" possible in paperbacks, or was this frankness describing something authors and readers considered new? I'll have a better idea, I hope, the more of these I read.

* * *

I bought this book back in 2014 in one of the used bookstores that still exist in the downtown area where I work. There used to be a lot more of those places, and I kick myself now when I think of all the paperback originals I could have picked up twenty or thirty years ago while I was browsing through different sections of those stores. Back then I wanted old magazines like Life or the Saturday Evening Post, or history books or else, as I grew older and less innocent, I browsed through the stores' photography sections. But you can't blame yourself for not wanting then what you want now. I'm just glad that there are still places where I can pay only $1.50 for this admittedly worn but still readably intact book. Over the past two years or so, while I began my pulp collection, I've also built up my vintage paperback collection. Not all of these are paperback originals, but many have the aesthetic virtues of the format. I like Popular Library paperbacks from this period for the layout, the fonts, and the cover paintings. More effort is made to sell the book with graphics -- necessarily since Terry Spain was an unknown quantity to potential readers -- than you see today in text-dominated covers emphasizing pre-sold authors. There's something campy about the packaging, I suppose, just as the contents inside seem campy today, but there's also an effort to reach out and grab the casual browser that's mostly missing today. I hope to read and review at least one novel each week from my collection, though not necessarily in as astonished detail as Time to Kill required. Not every novel may have as direct a link to pulp as this one had, but since paperback novels were direct descendants of pulp fiction, and part of the same golden age of storytelling, I hope pulp fans and general readers will enjoy this sample of wild things to come.

No comments:

Post a Comment